Stargazer sets sights on habitable exoplanets

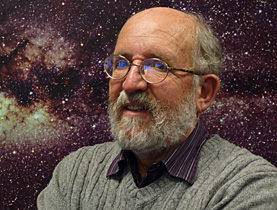

The 21st century is likely to see huge progress in our understanding of extrasolar planets, or exoplanets, Swiss astronomer Michel Mayor tells swissinfo.

Mayor, who identified the first planet outside our solar system, this week attended the launch ceremony in Paris for the International Year of Astronomy.

In 1995, Mayor and fellow astrophysicist Didier Queloz from Geneva University made a discovery that was to revolutionise modern astronomy. They observed the first planet outside our solar system, revolving around a star 42 light years away from Earth.

Twelve years later, they discovered Gliese 581 c, a potentially Earth-like planet orbiting the red dwarf star, Gliese 581. So far, over 300 exoplanets have been discovered, half by the team at Geneva University.

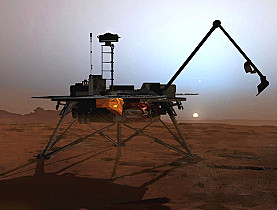

In March Nasa will launch a new orbiting telescope, Kepler, aiming to seek out Earth-like exoplanets hidden in the starlight of distant suns.

swissinfo: How important are the two figures being celebrated this year, Johannes Kepler and Galileo Galilei?

Michel Mayor: Both made enormous contributions to astronomy. They are the founding fathers, key figures, even if they lived years ago and physics has developed enormously since then.

Kepler undertook a mystical search to organise the universe – the harmonisation of planetary orbits. He eventually came up with three standard mathematical laws about planetary movement. This was a real turning point.

My work involves exoplanets but the mathematical tools frequently involve Kepler’s laws. And the mechanics are based largely on Galilei’s work.

Whether we like it or not, these two great figures are still present.

swissinfo: The 20th century saw extraordinary progress in our understanding of stars. Will this century be the turn of exoplanets?

M.M.: The 20th century was an incredible period for astrophysics. First we managed to understand how stars function. In 1937 Hans Bethe discovered the origin of the sun’s energy. After, there were major contributions looking at how stars formed, evolved and died. Another amazing contribution was nucleosynthesis – understanding the origins of chemical elements.

Another major 20th-century discovery was the start of mathematical cosmology. Based on Albert Einstein’s theory of relativity, man built an approach that might appear completely over the top and immodest with equations explaining the evolution of the entire universe.

The first exoplanets were discovered at the end of the 20th century. But it’s unbelievable what we have learned about exoplanets over the past 15 years.

There are now more than 300, but what impresses me more is the number of people working in this field. There has been a multiplication of different techniques – using satellites, Earth-based research and fundamental theoretical methods.

The first modest images of exoplanets were produced a couple of months ago, but we also know about their mass, orbits and their internal structure. We are starting to analyse their atmosphere to detect water, carbon dioxide and sodium, and we’ve directly measured atmospheric temperatures.

swissinfo: How difficult is it to detect an exoplanet?

M.M.: An exoplanet is lighter than a star, so the indirect detection methods involve monitoring disturbances in a star’s movement. But a planet’s mass is important, as if it’s too small, it won’t make the star move.

The other difficulty is trying to actually see one. Imagine you have a candle placed one metre from a lighthouse and you look at it from one thousand kilometres away. It’s obvious the lighthouse completely outshines the candle, preventing you from seeing it.

swissinfo: How will Nasa’s Kepler mission, planned for March 2009, help further our understanding of the universe and detection of new planets?

M.M.: The aim of the [three-year] Kepler mission is to study the number of Earth-like exoplanets that orbit at the right distance from their star and where life could possibly develop.

We now have lots of information about big exoplanets but they are less interesting. For life to develop you need relatively light rocky planets that are the right temperature. And existing machines have great difficulty detecting such planets.

Kepler could help us find such planets and tell us that around a certain star there is a very light planet with a one-year orbit.

I’m certain that in 20 years time we’ll then have the first space missions for exoplanets.

swissinfo: What are the chances that life exists on another planet in the universe?

M.M.: As a scientist I feel unable to answer that question.

There are likely to be numerous rocky exoplanets at the right temperature orbiting sun-like stars… but we just don’t know which ones are potentially interesting for life to evolve.

But that’s not the major problem. When all the right conditions are met, what are the chances that chemistry and biology create a living organism as complicated as a single cell? We really don’t know. Some people say if it happened here on Earth it could occur elsewhere – but we really don’t know.

Biology is not sufficiently developed to answer this question… We have to remain modest. The universe took several hundred million years to carry out its chemistry experiments on a huge laboratory – the Earth.

That’s the safe scientific argument. But personally I believe life is a kind of by-product of the laws of the universe and when the conditions are met then life is possible in one form or another.

There is nothing shocking about that idea. The atoms that we are made from come from inside a star. I’m quite happy with the idea that life exists elsewhere.

swissinfo: What are your expectations for the International Year of Astronomy?

M.M.: Astronomy is beautiful. And understanding the main aspects about the universe and how it works is fascinating.

We tend to pigeonhole culture – painting, music, other arts, and then science. But sciences like astronomy, archaeology or palaeontology are all part of culture. It’s a real shame not to know about the major advances in astronomy during the 20th century, for example.

But the International Year of Astronomy could also play another role. Over recent years the number of young people studying pure sciences like physics or mathematics has fallen. So I hope the exciting side of astronomy manages to generate interest among them and bring in new students.

swissinfo-interview: Simon Bradley

Exoplanets are planets outside our solar system.

The first exoplanet was discovered by Swiss astronomers Michel Mayor and Didier Queloz from the Geneva Observatory in 1995.

Since then over 300 exoplanets have been identified, although none can be seen by telescope. They can only be detected indirectly.

The overwhelming majority of exoplanets found so far are so-called “hot Jupiters”: large gas planets orbiting close to their star.

However, in 2007 Mayor and fellow astronomer Stéphane Udry discovered the first Earth-sized exoplanet, lying 20.5 light years or 120 trillion miles away, with a mass five times that of our planet.

More than 130 countries are celebrating 2009 as the International Year of Astronomy with events and activities designed to generate interest in the universe.

Launched by the International Astronomical Union and Unesco, the campaign officially begins with an opening ceremony in Paris on January 15-16.

The organisers are celebrating the 400-year anniversary of Galileo Galilei’s first use of an astronomical telescope and the publication by Johannes Kepler of Astronomia Nova, a tract which laid out the fundamental laws governing the movement of the planets.

For one event, groups in more than 30 countries at more than 150 venues will help amateur stargazers set up telescopes on pavements as well as in science centres to let passers-by observe the sun using special safety equipment.

Switzerland’s national opening ceremony is on February 5.

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here. Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.