‘Please don’t turn me into a heroine’

Pia Zanetti wanted to tell powerful stories through photography. Six decades later, she is one of the most renowned Swiss photographers of her generation. Her life's work is on display at the Fotostiftung Schweiz in Winterthur.

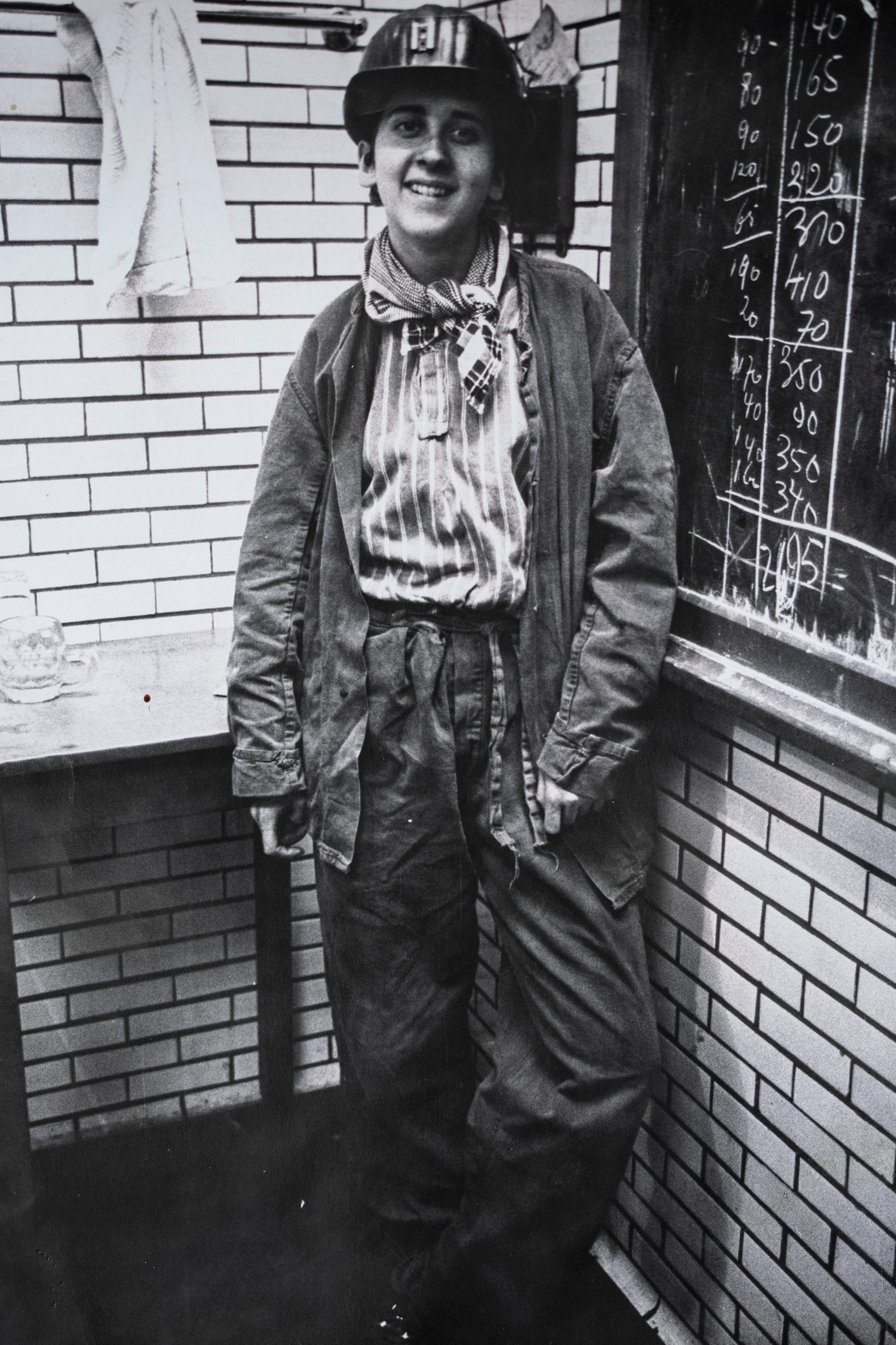

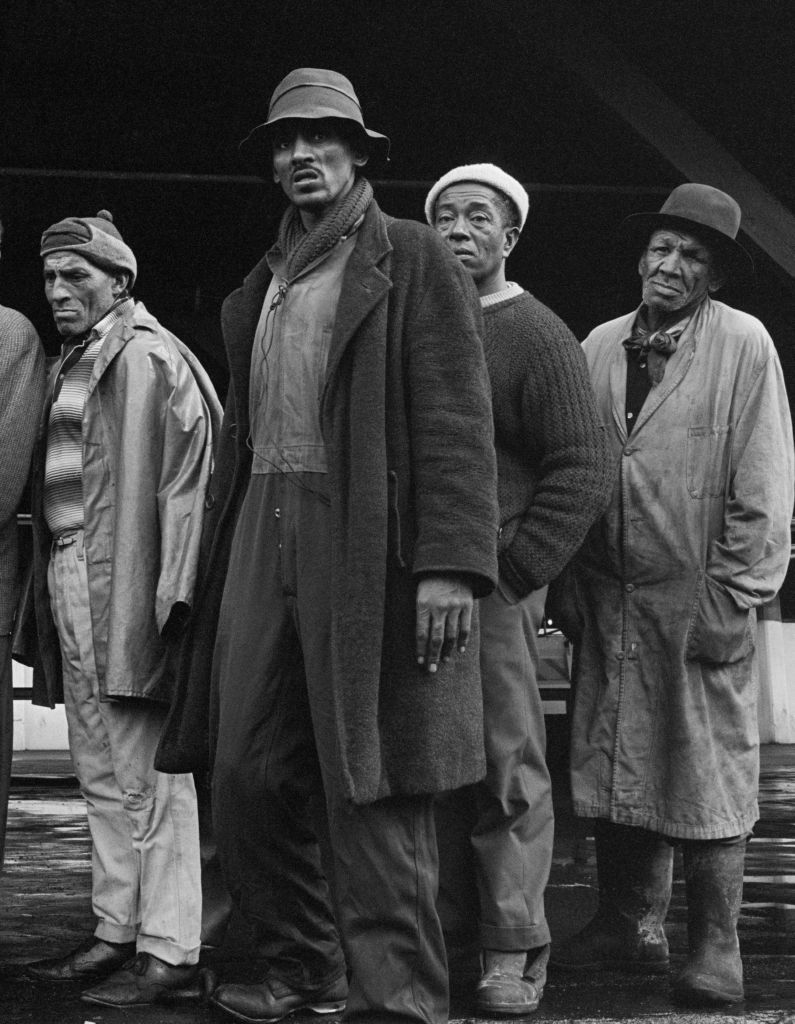

Pia Zanetti,External link born in Basel in 1943, is one of the most renowned Swiss photographers of her generation and one of the few women who managed to remain competitive in this male-dominated profession for several decades. As a young woman she wanted to see the world and tell powerful stories through her photography. She captured dramas big and small from fights against injustice to the fleeting moments of day-to-day life, showing people in the streets, at play or lost in thought. Her photography has a compassionate feel and puts regular people in the foreground.

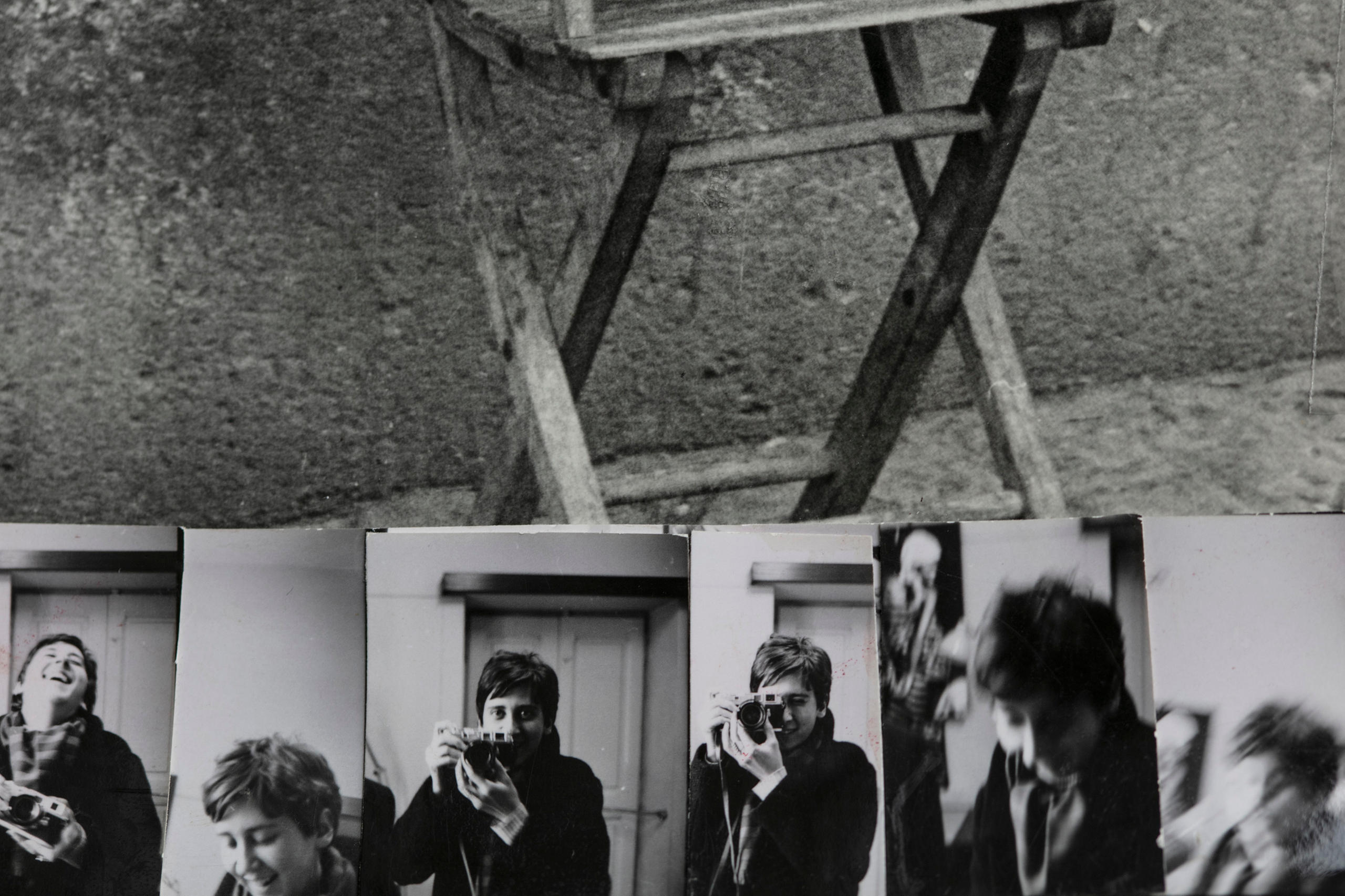

SWI swissinfo.ch: I am looking at the first picture of your monography (published alongside the exhibition), which shows three young men dancing on a stage. It was taken in 1960 when you were barely 17 years old. The photograph seems to emanate the distance of an observer, even though you could have joined in as the men on the stage were the same age as you. Have you always been an observer?

Pia Zanetti: The stage in the photograph is round and rotating. I did not want to go up there myself, I was too shy. So, observing was easier than participating. What’s more is that the photographers who worked for Magnum Photos were my heroes back then, and you can certainly recognise the Magnum style in this picture. Being able to make yourself invisible was extremely important back then. It was almost considered a disgrace to look straight into the camera. This was something I wanted to master. Margaret Bourke-White, who was a pioneer in American photojournalism in the 1930s, was my role model in those days.

SWI: You have been a photographer for 60 years. What has changed over time?

P.Z.: The working opportunities. What used to be a paid assignment for us is now called a “project”. If something attracted your interest, you simply submitted a proposal to your editor. In the same day, we could pitch three stories that were happening in faraway places involving travel. Editors would make their decisions on a whim and would often agree on the first pitch and also on the second. And if no immediate decision was made on the third pitch, they would be open for discussion once the first two assignments were completed. If we needed an advance, the cash desk would pay it out right away. The editors of the Woche newspaper even rented a small apartment in Zurich, only for us to have a place to stay when we were coming backing from Rome or London. This is unheard of today.

SWI: How did you handle new technologies?

P.Z.: It took me a long time to change to digital photography, but I never regretted it. I have never liked spending hours on end in the photo lab; on the contrary, I spent as little time as possible in the darkroom. I was always scared that my films would be blank!

SWI: Why did you want to become a photographer?

P.Z.: My brother was a photographer, and I was absolutely fascinated by his work. I also wanted to tell stories and see the world. What other profession enables you to do this? I knew that this was my only chance, however, I did not know whether I would succeed.

SWI: Did you get support or were you hampered in your efforts?

P.Z.: My mother was convinced that I would not be able to earn a living as a photographer. People thought there was no money in it. I shared a studio apartment with my mother. In the evenings, we would often have to scrape our money together and, for example, take a bottle back to the shops to get the deposit and buy a loaf of bread with it. I already knew back then that I did not want to lead such a poor life.

SWI: But wasn’t your brother proof enough that one could earn a living with photography? Why did she have such doubts?

P.Z.: That’s true, however, he was a man, and I was a very petite woman. My mother simply could not imagine it, so I first went to business school. When I was 17, I worked in an office for a year. I was very proud to earn some money and support my mother. However, I told everyone right away that I would not stay for long.

SWI: I have the feeling that you always looked ahead in your life, but now, if I may say so, you look back at your life’s work. How does it feel?

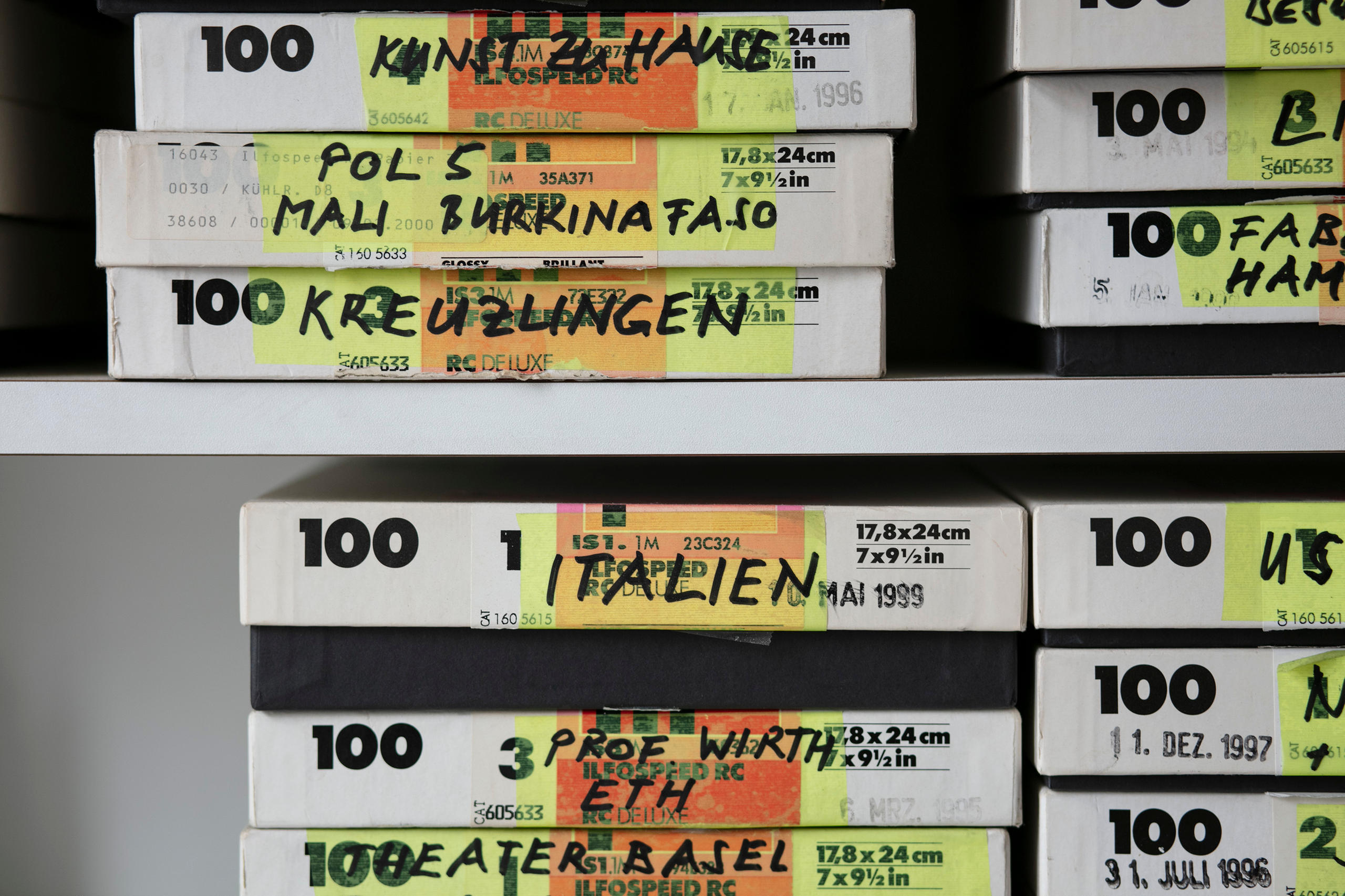

P.Z.: Yes, I guess you are right. Sixty years is a life’s work. When I started to organise my archives, the director of the Fotostiftung Schweiz Peter Pfrunder asked me to get in touch with him once I was done. On the one hand, I was incredibly proud that he considered exhibiting my photographs, on the other hand, I was scared. What would I put on display? Would my work be good enough?

The whole process of looking back took three years. Organising my archives turned into an analysis of my life. Most of the time, I had travelled together with Gerardo Zanetti, my late husband. Initially it was difficult to work without this second ‘voice’. I also developed a political consciousness during our work together, which, unlike Gerardo, I did not have in the beginning.

SWI: How is this political consciousness reflected in your work?

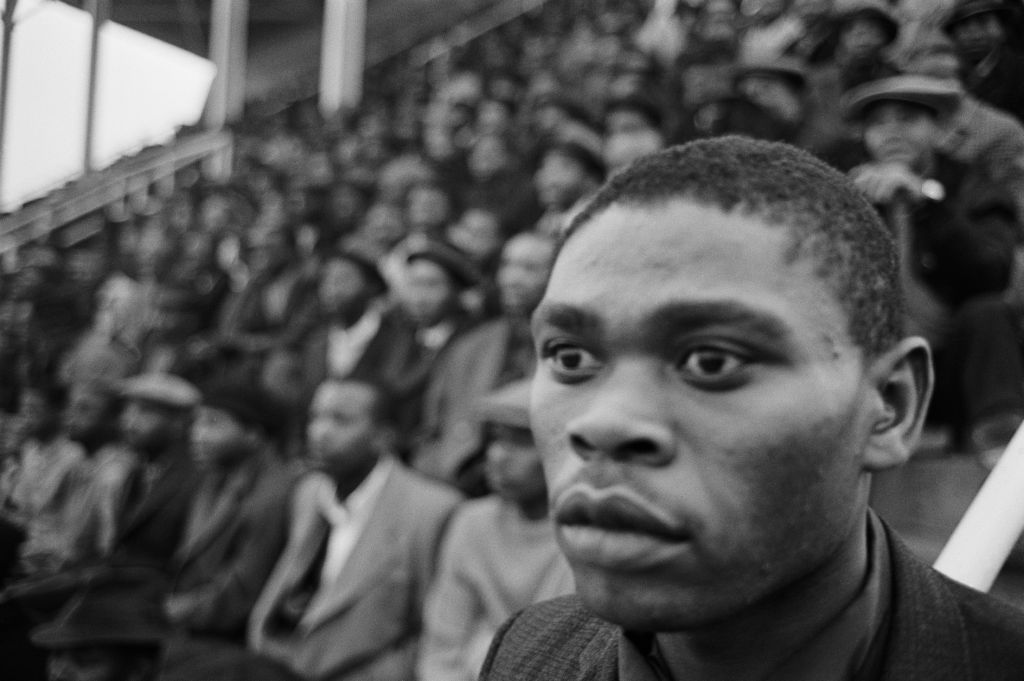

P.Z.: I remember an image I saw in South Africa. A good-looking young black man was standing behind a barbed wire fence holding onto the fence with his hand. For a split second, it reminded me of a photograph by Leni Riefenstahl, which stopped me from taking the picture. I was afraid because I had this particular image in my head.

In the end, my husband said: ‘Take the picture! We are alone.’ He was trying to say that nobody would get to see this image if I did not take it. We worked together for a long time, we were a very close and well-functioning team, however, I always suspected that we got the assignments because Gerardo was such a good journalist. He, on the other hand, thought the work was coming in because I was an excellent photographer. Later in life, I wanted to prove to myself that I could also work on my own.

SWI: Suddenly people call you a pioneer and a role model in the world of photography and journalism which was dominated by men not so long ago. How do you cope with this image, and were you aware of these gender roles earlier in your life?

P.Z.: To be honest with you, I love it and I enjoy the fame (she laughs). I find it extremely satisfying. I never used to be aware of the different roles, and I was never really interested in it. These {gender-specific} terms are way too big for me, I would never use them for myself. Please don’t turn me into a heroine. Many women who read something like this must think that they can’t meet the expectations. But it is important to know that I am hardly ever scared of anything, which comes as a surprise to many people.

SWI: But didn’t you say that you were scared of your films being blank….?

P.Z.: True – maybe technology scares me, but not many other things. When Gerardo and I arrived in Rome in the 1960s, I spoke a little Italian. I was not scared to throw myself into work and do some stories. I was very young and even looked younger than my age, like a girl. My work was often topical such as a papal visit to the Colosseum where I found myself among the lenses of the paparazzi who were all men.

SWI: Have you completed your life’s work? You are 77 years old. Are you putting your camera away or is this out of the question? What keeps you going?

P.Z.: Do you want me to order my coffin right away (she laughs)? I have to tell you in all honesty that I don’t feel like picking up my camera at the moment, which is also a surprise to me. However, we change and we have to accept it.

SWI: You haven’t analysed this yet?

P.Z.: Maybe I don’t want to. It feels liberating to go outside empty-handed, without a camera or a tripod. I am not like Swiss photographer René Burri, who went to the grave holding his camera.

I love my job, but I also have other interests besides my career. Back in the day, having my photographs exhibited was not that important to me. I am convinced that something new will come along and that I will feel like doing something new again.

The book of Zanetti’s photography was already sold out before the exhibition opened its doors. You can order the monography which was published by Scheidegger & Spiess and Codax Publishers and edited by Peter Pfrunder via the museum’s e-shop.External link

Sixty-seven photographs taken over six decades by the Swiss photographer Pia Zanetti are currently on display at the Fotostiftung Schweiz in WinterthurExternal link. Zanetti lived in Rome and London in the 1960s and travelled around the world with her camera. Like all other museums, the Fotostiftung Schweiz remained closed last month, however, depending on the Corona measures of the Confederation the situation can change any time. For updated information, please check the website of the Fotostiftung. The exhibition was planned to be on display from January 23 to May 24, 2021.

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

Join the conversation!