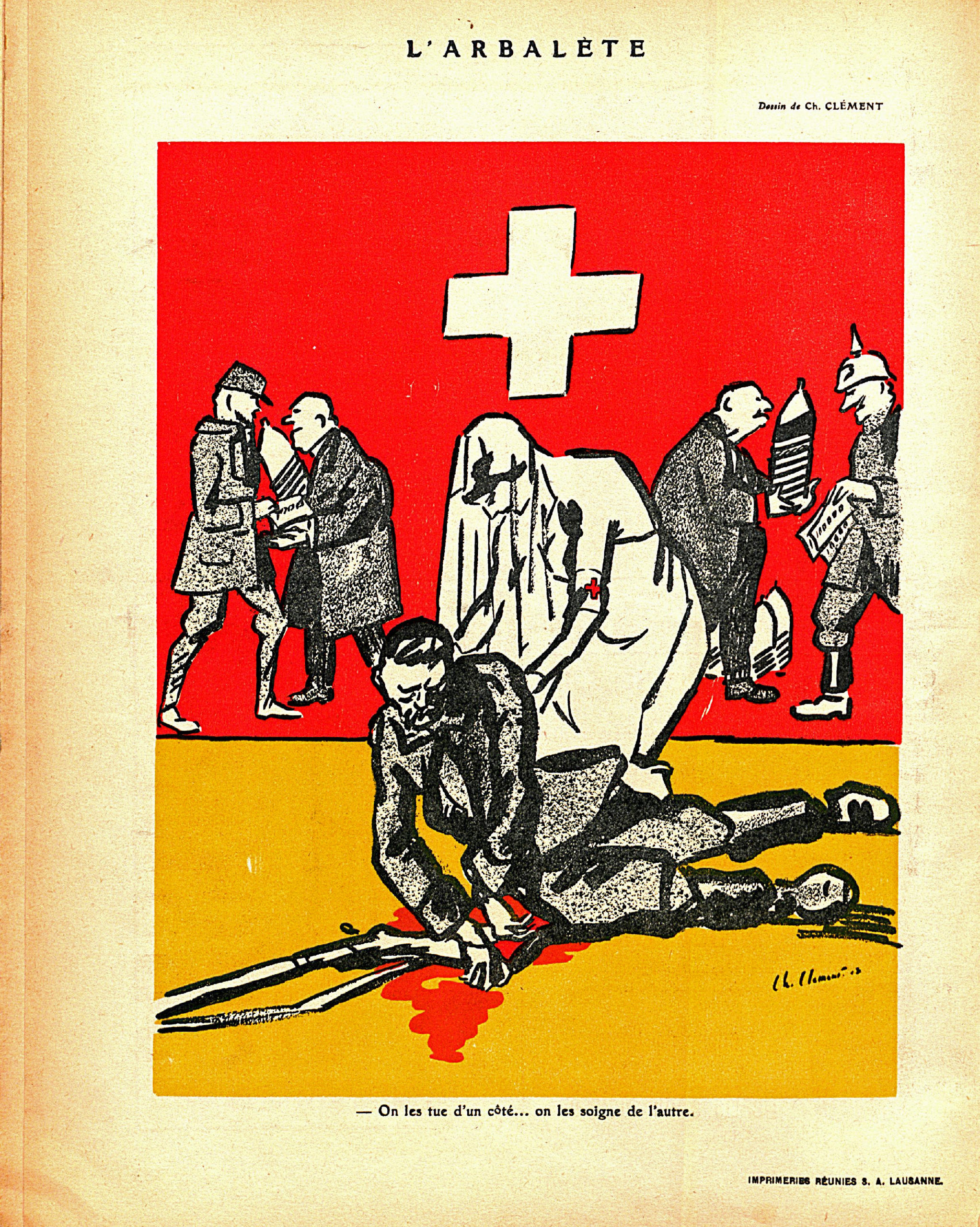

Arms trade: Swiss neutrality as business strategy

For the Swiss arms industry, neutrality has usually meant selling the same amount of arms to all nations – or, on rare occasions, none, so as not to annoy dictators.

There used to be a legend going around Europe that Swiss mercenaries polished their boots with the belly fat of fallen enemies. Warriors from the Alps fought on all of Europe’s battlefields and overseas in the colonies – a million and a half men all told. Today Switzerland no longer exports warriors, but it does export arms.

Switzerland’s share of the international arms trade is actually small. Between 2018 and 2022 it was 0.7% – whereas the US market share was 40%, Russia’s was 16% and China’s 5%. The proportion of arms in Switzerland’s total export volume is under 0.5%.

More

Ukraine war is a windfall for Swiss arms industry

Yet the idea of a neutral country, which professes to stay out of all conflicts, making money from war is inevitably denounced as hypocritical. As far back as the 17th century, neutrality was the main argument for providing mercenaries and strategically important goods to all and any belligerents. Even after 1918, neutrality was more of a help than a hindrance to the Swiss armaments industry, which was now geared to the export market.

The two Hague conventions of 1907, which provided the framework for neutrality, forbade export of state-produced armaments. Private industry was only required to treat customers even-handedly.

Switzerland has maintained that position down to the present:External link if arms cannot be supplied to Russia, they cannot be supplied to Ukraine either.

Even-handedness has mostly meant supplying both sides in wars. This meant that Swiss companies in the First World War sold detonation timers for artillery shells in large quantities. The technical know-how and skilled personnel came from the watchmaking industry. The federal government did not consider these exports as incompatible with Swiss neutrality.

Neutrality understood in this way also determined the relationship with nations on the losing side after the First World War. The Versailles treaty forbade Germany and Austria any armaments industry of their own. So these two nations transferred their technical know-how in the field to other, neutral countries.

More

Swiss arms exports still at odds with humanitarian tradition

According to Peter Hug, a historian and expert on the history of Swiss arms trading, that was how the armaments industry in Switzerland really took off. “Revanchist groups were organising the illegal rearmament of Germany and Austria from Switzerland and other neutral states. It was easy enough to do, because in Switzerland there was no need for official approvals for production or export of armaments. It was thus that advanced technologies for exportable military systems like the 20mm rapid-fire gun came to Switzerland.”

More

Emil Bührle and the art of war

It was only in 1938 that the Bern government – due to a people’s initiative – was obliged to police the export of arms. Implementation was very lax, however, as Hug notes: “The Defence ministry, supposedly responsible for approving industry actions, showed little motivation and hardly bothered to look.”

In the Second World War, Switzerland exported guns and ammunition to the tune of CHF10 billion – in 1941 it was over 14% of the nation’s entire exports. As part of the Independent Commission of Experts on the Second World War, known as the Bergier Commission, Hug was able to determine that 84% went to Germany and the Axis, and only 8% each went to the Allies and neutral states.

Even more strategic importance was attached to the production of militarily significant items such as precision tools, ball-bearings and machine tools, which were used in producing armaments or supporting armies in the field in other ways. Here too, Germany got the lion’s share.

In 1943 British foreign minister Anthony Eden complained: “Every franc earned by Switzerland from arms sent to Germany is prolonging the war.” Along with Swiss cooperation with German banks, this created the picture internationally of a Switzerland that had made money without scruple out of the Second World War.

No moral neutrality

Switzerland took this tarnished reputation into the Cold War era. Neutrality was a problematic issue now. In a divided world, where Switzerland wanted to belong to the Western bloc, it was not so easy to spread arms exports around.

In 1968 there was a real scandal, when it emerged that the Oerlikon-Bührle arms company had been supplying both sides in civil wars with the help of forged declarations. A popular initiative now demanded an end to all arms exports from Switzerland. Though it was eventually turned down by the voters, the initiative led to new federal legislation on armaments. In future no arms were to be exported to places where there was a war going on or likely to break out.

According to Hug, there now began a more careful monitoring of arms exports. “But there was still plenty of room for manoeuvre,” he says. It turned out that the federal government only gave its approval to arms exports to states where other European countries were not likely to object. This approach, Hug notes, is still being used today.

Neutrality also served as a justification for the arms trade in the Cold War era. “We are not the world’s policeman,” declared Rudolf Bindschedler, a foreign ministry bureaucrat and an important strategist of Swiss neutrality, in 1976. What this meant was that it was not up to Switzerland as a neutral state to deny arms supplies to anyone in particular. At the time, the export of heavy water for producing plutonium to the military regime in Argentina was being criticised, as the generals were suspected of trying to make their own atomic bomb.

Where regulations actually forbade export, one way Swiss arms companies got around them was by contracting the work out. The SIG company did not export any of its automatic rifles to the military regime in Chile, but it did send the plans and tools so that they could be produced out there. At a price, of course.

More

Napalm from the Alps: How the Swiss developed a lethal incendiary agent

Discussion has gone on down to the present day about what comes under the arms legislation and what doesn’t. Pilatus training aircraft, for example, have no civilian use – the planes cost too much. When the federal government announced its intention in the 1990s of placing these under the arms legislation, Parliament disallowed it. The people’s representatives saw no difficulty even when Pilatus planes were fitted with arms at a later stage.

Asked what the biggest single leverage point for the armaments industry is, Peter Hug says simply: “Lobbying the parties on the right.”

In 1996 there was a tightening of the legislative provisions on the arms trade, again after a people’s initiative. At the same time a new Goods Control Act brought the export of “particular military items” and what had become known as dual-use technology – like NBC protective suits, training aircraft and GPS systems – under export controls.

Yet since 2009 the situation has seemed to be loosening up. On the one hand, Swiss voters have expressed support for the armaments industry in another nationwide referendum. On the other hand, purchasing by the Swiss Army itself has dwindled since the end of the Cold War.

Pacifism for the wrong reasons

When Russia annexed the Crimean peninsula, the whole mood in Europe changed. “Since then, military expenditures across the Northern Hemisphere are in a definite growth pattern. In the wake of this, the Swiss government has relaxed its policy on export approvals,” says Hug. The armaments lobby had already complained in 2013 that “the Swiss security industry is being put at a disadvantage.”

In 2016, in a significant step, the federal government relaxed its policy when it decided to continue supplying Saudi Arabia in spite of its involvement in the war in Yemen. A civil war should be considered as legally different from a war between states, said the government. That Saudi Arabia as a belligerent state could get arms from Switzerland for CHF120 million ($134 million) in 2022 while Ukraine got none, has baffled many observers.

Switzerland found itself once before in this kind of situation. In 1946 the government forbade the export of arms entirely. But it was not really as a gesture to the war dead of Europe. By the end of the war, Bührle had turned to providing Fascist Spain with big guns, since Germany could no longer pay. The UN called this supply arrangement “a danger to peace” and decided to impose an embargo. Switzerland was now under pressure. In order not to anger Franco with a “one-sided arms export ban”, the government decided to ban all such exports.

In Hug’s view, this became a precedent for the present situation. “This capitulation to Franco was not seen for what it was by pacifists, who have been supporting the idea of an arms export ban ever since. Yet in the case of a war of aggression, it helps the aggressor and hampers the victim from defending itself as is its right under the UN Charter.”

More

Translated from German by Terence MacNamee

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.