Chernobyl legacy hangs over Swiss energy policy

Twenty years after the Chernobyl nuclear disaster, the political fallout is still reverberating in Switzerland. Two experts from opposing sides analyse the implications for nuclear energy.

In the aftermath of the catastrophe on April 26, 1986, Swiss voters approved a moratorium on building new nuclear plants, but in 2003 they backed away from phasing out nuclear energy altogether.

Johann Schneider-Ammann, president of the Swiss mechanical and electrical engineering industries (Swissmem), warns that energy needs are likely to outstrip supply by two-thirds in the next three decades.

Energy specialist, Rudolf Rechsteiner, says nuclear power can be replaced by alternative sources of energy, such as solar power, biogas and wind turbines.

swissinfo: What did the Chernobyl disaster mean to you at the time?

Johann Schneider-Ammann: Uncertainty, concern. Could something like that also happen here in Switzerland? But then it led to other, better technologies. A consequence of Chernobyl was that, worldwide, safety at nuclear power plants was significantly improved.

Rudolf Rechsteiner: The pressure to build a nuclear power plant near Basel was lifted. What the Swiss government had always said would not happen – that a nuclear reactor could explode – had happened. One couldn’t drink milk anymore and all the vegetable farmers had to destroy their crops. It was the beginning of the end of nuclear energy.

swissinfo: What effect did Chernobyl have on a political level in Switzerland? The Cold War was still a reality then.

J. S-A.: Popular support for the peaceful use of nuclear energy sank to a very low level. In political terms, it was a big boost for opponents of nuclear power. At the time of Chernobyl, the Soviet Union was already starting to crumble, and this had compromised safety in both organisational and technical terms.

R. R.: The incident was played down, and attributed to “Russian sloppiness”, and the generation in power at the time, and which is still active in the electricity industry, stubbornly refused to learn any lessons from it. It’s only a generation later that new techniques, such as wind power or cogeneration – combining heat and power, are being considered.

swissinfo: What concrete repercussions were there for Swiss energy policy?

J. S-A.: After Chernobyl a moratorium came into force along with pressure to abandon nuclear energy. Despite the government’s recommendations to reject a moratorium, the public approved one in a vote on September 23, 1990. Since then, any talk of building new nuclear power plants in Switzerland has been taboo.

R. R.: A new plant near Basel was out of the question, and the industry is still doing everything possible to play down the consequences. The industry has also tried to buy influence among politicians in Bern. But the main argument in favour of nuclear power – that it was so cheap, it wasn’t even worth writing accounts – has been exploded.

swissinfo: In the 20 years since Chernobyl, some countries have decided to abandon nuclear energy; others are planning or building new nuclear power plants. What is Switzerland going to do?

J. S-A.: Switzerland must find a way to guarantee its future energy requirements. If we do nothing, within 25-30 years we will only be able to produce domestically about two-thirds of the energy we need. The voters will decide whether we build more nuclear energy plants.

R. R.: Sources of alternative energy, such as wind turbines and solar power, are growing by 30 to 40 per cent a year. Then there are other possibilities such as biogas, geothermic energy or heat pumps. Provided the incentives are in place, they will play an important role in energy production in the coming decades. Such moves are alreday underway in other countries.

swissinfo: Studies suggest Switzerland will experience energy shortages in the coming years. Does this mean new nuclear plants will be back on the agenda?

J. S-A.: Voters made clear in a national ballot on May 18, 2003, that they wanted to keep open the option of building new plants, when two initiatives calling for its phasing out were decisively rejected. It is therefore time to discuss how we are going to replace the energy we get from our own reactors as well as that we import from French nuclear plants.

R. R.: The energy industry in Switzerland is still totally fixated on nuclear power. If the market was subject to proper competitive pressures these dangerous “cathedrals” would lose both support and investment. People would prefer solar energy panels on their roofs.

swissinfo: Are we as a society then ready to accept alternative forms of energy, given that these would require changes in our way of life?

J. S-A.: Nobody appreciates being told what to do, especially if it is linked to an ultimatum. But given the freedom to choose, we become willing to accept responsibility and keen to achieve. We need the right conditions in place to be able to pursue our common interests with regard to energy, without imposing limits on what we can achieve.

R. R.: I’m convinced that the electricity industry can’t refuse to invest in renewable energy resources for ever. It will have to give up its opposition to new legal conditions. From an economic point of view alternative forms of energy are superior to nuclear power.

swissinfo-interview: Urs Maurer and Rita Emch

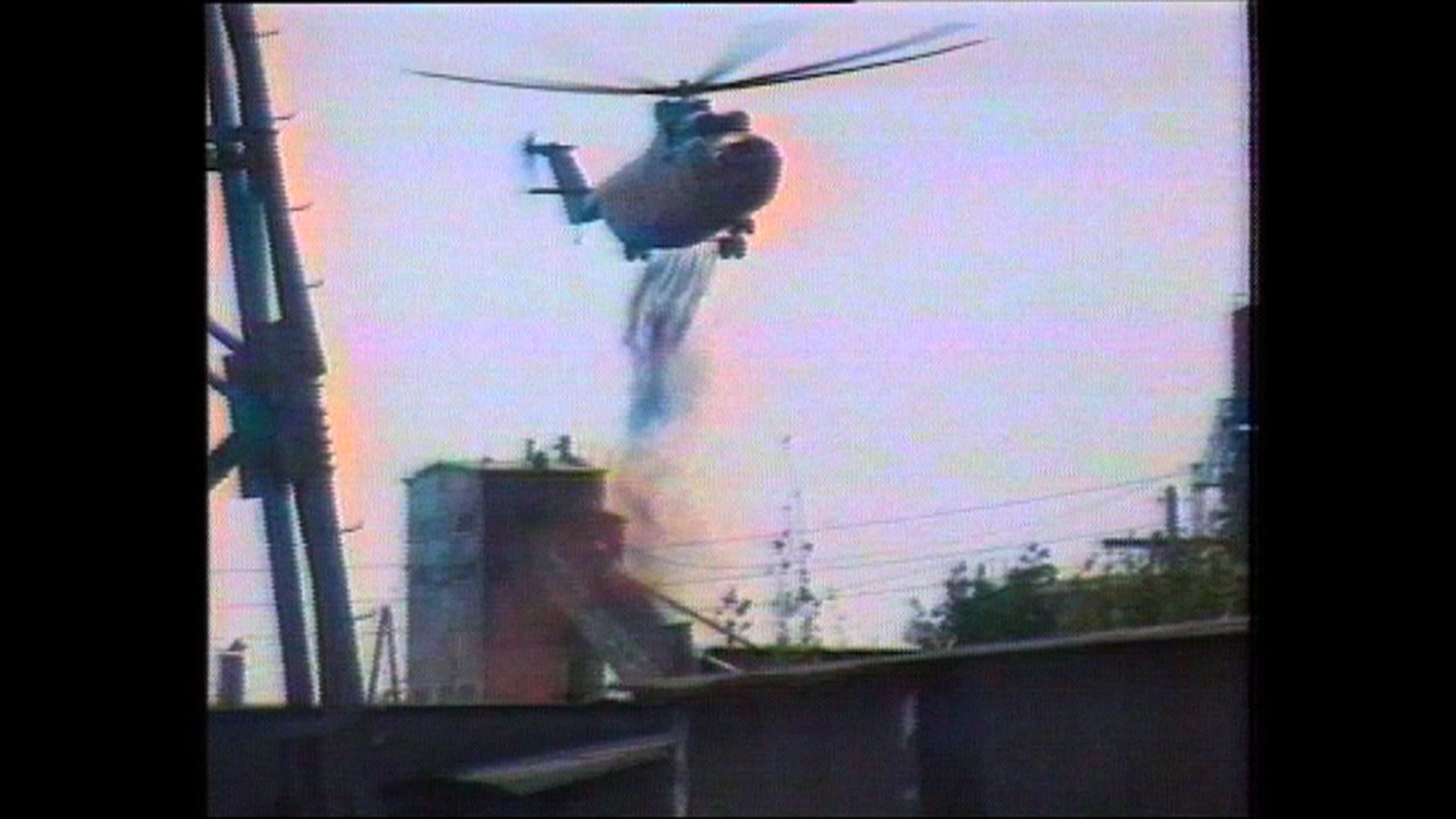

April 26 1986: Reactor four at the Chernobyl nuclear plant in Ukraine explodes, releasing a cloud of radiation.

May 3 1986: The Swiss authorities publish precautionary measures against radioactive fallout, advising pregnant women not to drink fresh milk, and to wash thoroughly all fresh produce.

21 June 1986: Over 20,000 protest against nuclear energy outside a power plant in Gösgen.

1988: The government shelves plans to build two new reactors, in the face of growing public opposition.

23 September 1990: Voters approve a ten-year moratorium on the building of new reactors.

22 October 1998: The government signals it is in favour of a phasing out of nuclear energy.

18 May 2003: Voters reject a proposal for a new moratorium on building new plants, as well as an initiative calling for a phasing out of nuclear energy.

1 February 2005: A revised nuclear energy law comes into force. A referendum on building new plants is planned.

Switzerland has five nuclear power plants, capable of producing 3.2 Gigawatts of electricity, including:

Beznau I und II (operational from 1969, 1972)

Mühleberg (1972)

Gösgen (1978)

Leibstadt (1984)

Nuclear power supplies 38% of Switzerland’s energy (this can rise to 45% in winter), compared with a European average of 33%.

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.