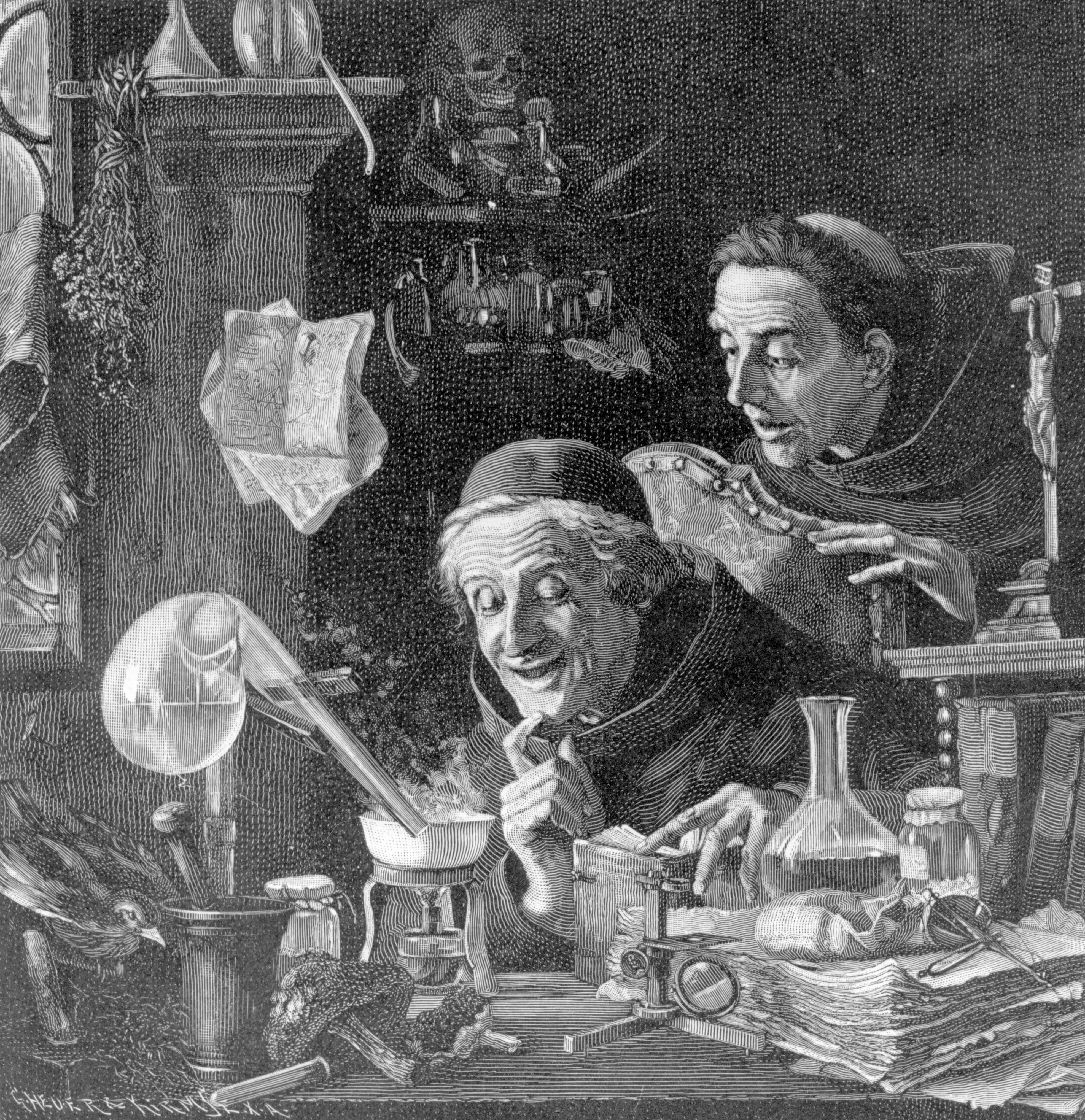

Let the chemical games begin!

The International Year of Chemistry has been officially launched in Switzerland with the aim of raising awareness and whetting the appetites of young boys and girls.

swissinfo.ch dodged the (controlled) chemical explosions in Bern on Tuesday and spoke to a Nobel Prize winner, the secretary of state for education and research and a top female scientist about the importance and their love of chemistry.

“It’s the surprises,” Richard Ernst, who was awarded the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1991 for work on magnetic resonance spectroscopy, told swissinfo.ch.

“Experiencing surprises was how it started. In our attic I discovered a box full of chemicals which belonged to an uncle who died in 1922…” In a chemical accident? “Er, no, they were photochemicals. So I took them down, started to play with them and I was excited by what happened.”

Ernst, whose work laid the basis for MRI scans among many other applications, said it was producing something he couldn’t understand and then finding a reason for it that stimulated his interest in chemistry.

“I wanted to understand why that all happened in my basement and why I survived and why our house survived!”

The sprightly 77-year-old believed this was the best way to attract young people to science.

“Let them do experiments! Sometimes people say chemistry is too dangerous – you can’t do this and that with children – but that’s not really true. There are a few rules which you have to obey, but otherwise you can do a lot of experiments,” he said.

“You experience the joy of discovery very often in chemistry.”

Does science receive enough support in Switzerland? “I think it’s a very positive climate here – among the public and in politics too. Our universities are relatively well supported by the government,” he said.

“The link between science and industry is very close in Switzerland – it’s very clear that the country gains from investment in science. It’s so obvious that even politicians understand it!”

Brain drain

One pro-science politician is Mauro Dell’Ambrogio, secretary of state for education and research, who addressed 200 invited guests and afterwards told swissinfo.ch that this link was central to combating brain drain.

“The link between industry and academic research is one of the keys to not only attracting but also retaining talented people. Until now we were draining brains from all over the world.”

This, he said, was one of the secrets of Switzerland’s Nobel Prize success. Per capita, the country’s 24 Nobels – six in chemistry – are a world record.

“I don’t think Swiss people are more intelligent than average. But Switzerland has always been open to talented foreigners,” Dell’Ambrogio said.

“In the middle of the 19th century, when the Federal Institute of Technology in Zurich was founded, of 18 professors 16 were foreign. Today, more than 40 per cent of university professors don’t have a Swiss passport. I think that’s more or less unique and the key to this success.”

However, he acknowledged challenges to maintaining this world-class level, including a shortage of science teachers and difficulties in convincing girls to study science. He said one possible solution to the former would be to pay science teachers more than teachers of, say, languages.

“We have to open a discussion about it. That’s generally what happens in the market: if you have a lack of qualified people, the reaction of the market is to pay them better. I ask myself why the same principle isn’t accepted in public administration.”

Female minority

Helma Wennemers, a chemistry professor at Basel University, is passionate about spreading the chemical word to young children and is an exception to the rule that few women reach the top in science.

“To be honest, my schoolteachers were not the ones who enthused me about chemistry,” she told swissinfo.ch (listen to audio for extended interview).

“But I decided to study food chemistry because I wanted to do something to improve the value of food. Luckily this involved studying chemistry as the main course – and I never looked back.”

Wennemers, 41, admitted that female chemists were still in the minority. She pointed out that although one in three students who start a chemistry degree is female, the higher you get – in industry and academia – the smaller the percentage.

“Maybe you need more possibilities, more visions how to combine child day-care centres with professional life,” she said.

“Also, when I look at projects we’re doing for smaller kids, I feel that children are still taught from society that sciences are for boys, languages are for girls. Obviously with the events that we’re going to do throughout this year (see link) we’re going to try to change that and get girls interested.”

The International Year of Chemistry 2011 (IYC 2011) is a worldwide celebration of the achievements of chemistry and its contributions to the well-being of humankind.

It has been organised by Unesco (the United Nations science agency) and the International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry.

Under the unifying theme “Chemistry – our life, our future”, IYC 2011 will offer a range of interactive, entertaining, and educational activities for all ages. The Year of Chemistry is intended to reach across the globe, with opportunities for public participation at the local, regional and national level.

(Source chemistry2011.org)

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.