Patent system needs overhaul, say researchers

Markets are much better than patents in stimulating intellectual curiosity and discovery, according to Swiss-led research.

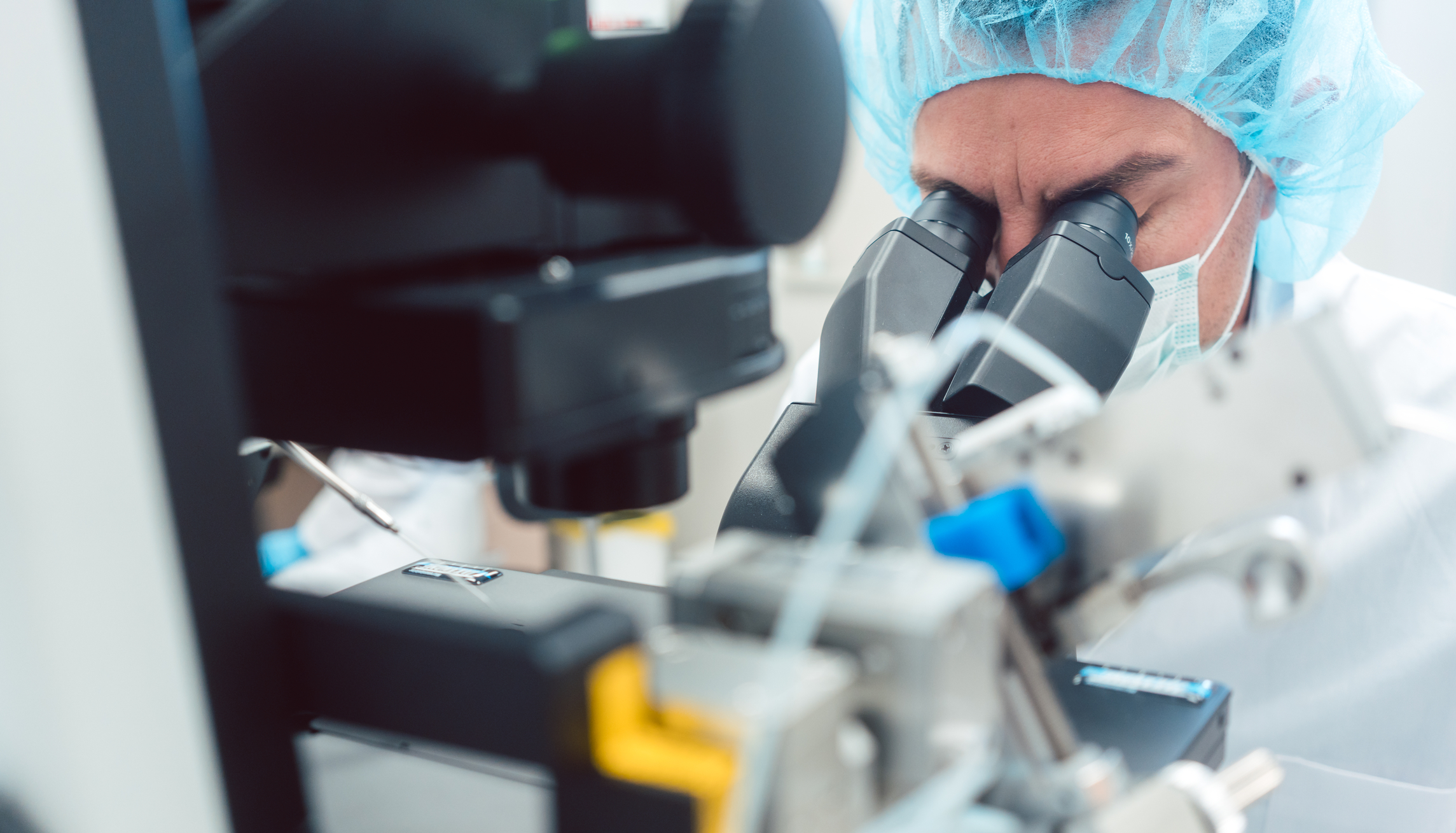

An international team, led by Professor Peter Bossaerts from Lausanne’s Federal Institute of Technology, carried out experiments to quantify the ways patent systems and market forces might influence someone to invent and solve intellectual problems.

Their findings were published in the latest issue of the journal Science.

The researchers claim that a market economy, where inventors buy and sell shares of the key elements of their discoveries, beats the winner-takes-all patent system, especially in terms of the number of beneficiaries, levels of collaboration and pace of development.

“From a classical economic point of view, the result is rather surprising,” Bossaerts told swissinfo. “The experiments showed us that the patent system works, but the market system also works, and in some ways it works much better.”

The problem with patents, argues the research team, is that they give the prize to the winner only; whoever comes in second or third walks away empty handed.

For the patent system to work well, “a large number of people need to think they’re the absolute best”, said the professor. The economic theory behind patent regulation even assumes that all people have an equal chance of being the best.

“But in reality very few of us think we’re the person most likely to come up with a unique solution to a problem before anyone else and so very few of us are likely to even try to solve a difficult problem. We just assume that someone else will beat us to the patent punch,” he explained.

Yet at the same time people are generally overconfident, he said.

“Eighty per cent of people will tell you that they are better than the median,” he said, adding that this is a statistical impossibility, but one that can be exploited in the marketplace to generate trade.

Rucksack game

In the “rucksack” experiments, participants were given a large number of items to pack into a bag that could not possibly hold all of them; the task was to try to work out how to maximize the number of “valuable” items they could fit into the bag.

Several participants had to solve one set of problems using a system similar to a traditional patent scheme, with a reward for working out the solution first.

The second set of problems was solved under a free-trading market regime where participants were encouraged to buy and sell “securities” attributed to each of the items.

The result was that several people in the “market” groups were able to benefit financially by coming up with a solution that was workable yet didn’t fully resolve the problem.

“They could solve only part of the problem – figure out a few items they believed would be in the solution, or those they thought wouldn’t be there – and focus on buying and selling those,” said Bossaerts.

For the Lausanne-based professor, the inventor retains the advantage, even in a free-market system “but you also give the second and third person a chance to profit from their work as well”.

It also led to numerous people trying different ideas each time the game was played.

Real world application

This theoretical approach could easily be applied to the real world, said Bossaerts, taking the example of a fuel-cell catalyst.

“If a scientist is really convinced that platinum, for instance, is the best catalyser for his fuel cell, the best way to go, he would go out and buy a bunch of platinum futures, knowing that once his invention got into the public domain, the items that go into that invention – in this case, platinum – will go up in price.”

Without a patent on the invention, other people would also be free to create platinum-based fuel cells. But there would still be a benefit to being the first.

That inventor would be the one able to buy up platinum futures when the prices were at their lowest, he explained.

Not convinced

But not everyone is won over by the new research.

“It’s an interesting game-theoretic experiment, but it doesn’t really give me any reliable information that market systems perform overall better than a patent system,” said Felix Addor, deputy director general at the Federal Institute of Intellectual Property.

After the free market, the patent system is a second-best solution, with disadvantages, such as temporary exclusivity, limited access and transaction costs, said Addor, who is also a professor at Bern University.

“But up to now there is no better alternative,” he said. “The patent turns an intangible invention into a tangible asset, which is tradable, and doesn’t lead to the market dominance of the winner.”

swissinfo, Simon Bradley

Requests for international trademarks hit a record last year, but have started to slow as the economic crisis unfolds, according to the Geneva-based World Intellectual Property Organization.

Trademark applications under the “Madrid system” in which businesses seek protection in foreign countries they designate totalled 42,075 in 2008, a rise of 5.3 per cent.

Switzerland climbed to number five in the rankings for the number of filings, with Nestlé and Novartis occupying the 2nd and 5th company rankings.

Patent filings from Switzerland rose by 8.6 per cent to 2,885 for last year.

Economic innovation can be measured in a number of ways: products and services, production and delivery methods, business models and marketing – to name some.

Switzerland has a long history of producing great innovators. These include: Alfred Escher (Credit Suisse bank, Swiss national railways, Swiss Life and the federal Institute of Technology), Henri Nestlé (Nestlé) and Charles E L Brown (ABB).

Switzerland is at the top of most charts that measure international competiveness in innovation (World Economic Forum, Economist Intelligence Unit). However, there are signs that this status is coming under threat.

There is currently a deficit of around 3,000 engineers and scientists needed to fill jobs in Switzerland. BCG estimates this shortfall could double by 2016.

Two-thirds of Swiss companies surveyed planned to increase R&D expenditure outside of their home country. In comparison, 40% said they would increase capacity inside Switzerland. In the past decade, R&D spending abroad rose 1.4 times faster than at home.

Switzerland churns out more patents to protect intellectual property rights per head of capita than any other European country. But the country saw just 3.5% new businesses in 2004 compared with 18.3% in New Zealand, 17.4% in Germany and 10.3% in Hungary. This represents a low conversion rate of ideas into enterprises.

The World Bank estimates that it takes 20 days on average to set up a business in Switzerland – five days in Singapore and two days in Australia.

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.