Why Americans are ‘adopting’ Swiss alpine farmers

From New York to California, upscale American grocers and speciality food store owners are “adopting” Swiss dairy farmers to bring hard-to-find alpine cheeses to the United States, while supporting a unique way of life in the Alps.

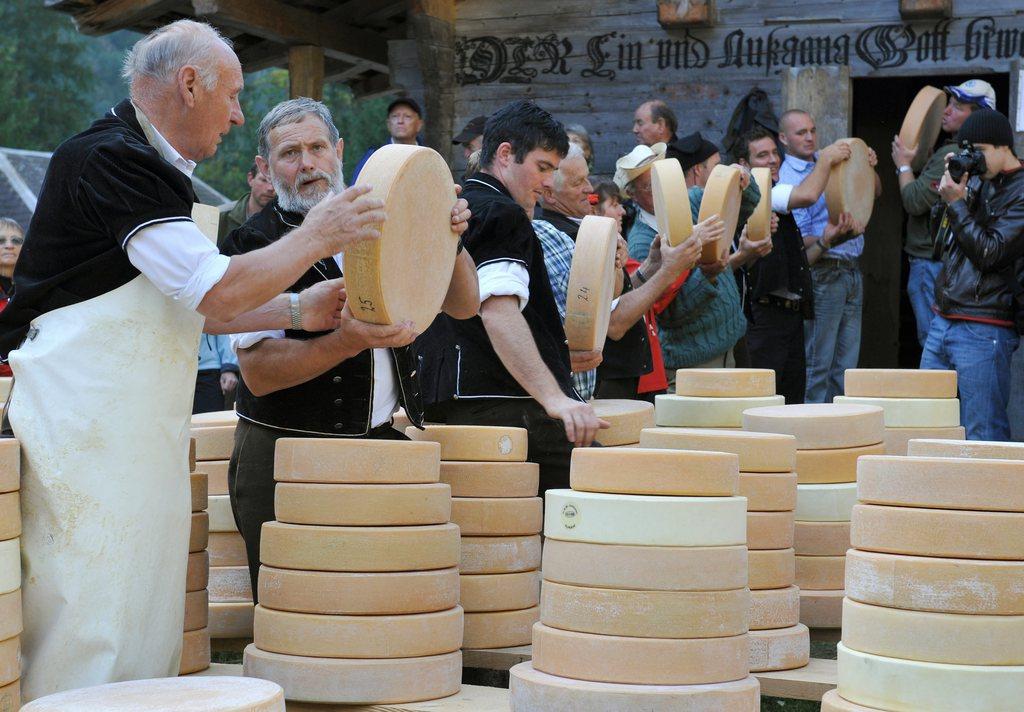

The concept comes thanks to a private business called Adopt-an-Alp that’s run by a Swiss expat in Florida. It hinges on personalised business-to-business matchmaking. The company helps American retailers and restauranteurs find Swiss farming families making Alp Cheese (Alpkäse in German), a variety of full-fat, raw-milk cheese that’s nearly impossible to find on this side of the Atlantic. When the cheese is ready in the autumn, the Americans promise to buy at least ten wheels of cheese from a farmer of their choosing. The farmers set the price. There is no contract.

Alp Cheese has a story that might resonate with American consumers willing to spend more on higher quality food. To make the cheese, farmers spend summers in Switzerland’s high alpine regions tending cows and turning the milk into cheese on the spot – an ancient, organic tradition.

+ Read about the role of “climbing cows” in the tradition

The farmers help build enthusiasm for the cheese by sending updates and photos of the summer cheesemaking process to their American counterparts, who then use those materials in promotions.

“Transparency in where your food is coming from and what’s in it is a definite trend I’ve noticed among more and more (Americans),” says Jess Weiland, the food and farm director for the High Desert Food and Farm AllianceExternal link, a non-profit group in Oregon that promotes direct links between farms and consumers. “The connection is really important and it’s increasingly becoming more important.”

So far this year more than 60 American businesses have used Adopt-an-AlpExternal link to connect with 27 dairy operations that span Switzerland from the pastures high above the Rhone valley in the west to the mountains of southeastern Switzerland. Of Switzerland’s 26 cantons, 14 of them produce Alp Cheese, and all 14 are represented through the business.

“You just adopt the one that you feel fits you the best,” says Sonja Hoffmann, owner of RacletteCornerExternal link, an online shop based in South Dakota, who recently adopted Alp Maran near the ski resort of Arosa.

“That’s the only place making raclette in [canton] Graubünden,” she says. “That’s my heritage. I’ve been there before.”

Transhumance

Adopt-an-Alp is the brainchild of Caroline Hostettler, a Swiss expat and entrepreneur who has built a career around importing fine Swiss cheeses, in part, to improve the “horrible state of the American cheese landscape” that greeted her when she first moved from the western Swiss town of Biel to Florida more than two decades ago. For years, if you were American and wanted a properly aged Gruyère, you probably went through her.

Hostettler’s work growing that business, Quality Cheese, not only helped move the needle little by little on American respect for European cheeses, but it also put her in contact with many Swiss farmers who practice “transhumance,” or the moving of livestock between grazing areas in accordance with the seasons. Alp Cheese is a direct product of transhumance since it can only bear the name on its label if it is made on the “alp”, the summer mountain pastures where cows graze freely on a wide variety of wildflowers and natural grasses. The cheese must use raw milk from those cows, exclusively, too. Different cows and different pastures mean every farmer’s cheese is unique.

“I just got more and more fascinated with that,” Hostettler says. “It’s not an easy lifestyle that these farmers lead working 16 hour days but it can be a very satisfying one.”

More troubling to her: The number of people doing this is decreasing, slowly but steadily, she says, pointing to statistics by the Swiss Alpine Farming AssociationExternal link that show 15,000 people worked on 6,800 “alps” in 2017. That’s down from 17,000 people on 7,200 alps in 2013. A survey done by Swiss government authorities in 2013 found more than half of Swiss dairy farmers were considering abandoning the tradition.

“I don’t think I can single-handedly change something but I can keep a foot in the door and keep things going slower,” Hostettler says. “One night after dinner I told my husband we should do something to make people aware of this tradition.”

Cheese

Alp Maran, the one the RacletteCorner adopted, sits at about 5,500 feet near Arosa and is home to 60 cows and some goats, pigs and sheep. It’s not a family operation but part of a unionised, community dairy that manages 400 cows across three other alps, too. In summer all of the cows pump out 100,000 gallons of milk that master cheese-maker Walter Niklaus and a team of five employees convert into Alp Cheese and a tangy variation called Alp Grottino.

“Since we’re a very small operation it’s very important to us that we’re able to deliver our cheese to various customers at a good price and not be dependent on any bulk buyers,” says Niklaus. Each year he exports about 1,100 wheels, about 5,500 kilogrammes, to the US. “Adopt an Alp lets us [tell customers] about our time in the mountains and at the dairy.”

Swiss cheese exports to the United States as a whole grew by about 2.2% between 2016 and 2017 to 8,454 tons, according to a report by TSM Treuhand in the Swiss capital, Bern. That’s a fraction of the 116,000 tons of cheese Switzerland exported to the world in 2017, a 2.1% year-on-year increase. Most of that cheese goes to the European Union, and specifically, Germany. Manuela Sonderegger, director of public relations for Switzerland Cheese MarketingExternal link, says Germans ate nearly 32,000 tons of Switzerland-made cheese in 2017.

As for Americans, Le Gruyere is by far the most popular variety of Swiss cheese exports. Last year, more than 2,800 tons of the sharp, hard cheese came to the United States, figures show. That’s second only to Germany once again, which imported 3,224 tons of Le Gruyere over the same time period. Emmentaler – or Swiss Cheese as it’s often called – ranks a distant second in the US with 508 tons shipped to American markets. Ready-made fondue packets take third.

And Alp Cheese? In 2013, AlpFUTURExternal link, a survey of farmers and herdsmen done by the Swiss Federal Institute for Forest, Snow and Landscape Research among other organisations, found Swiss farmers at that time were making roughly of 5,000 tons of Alpkäse a year. That made the cheese the country’s “most important alpine-farming product,” the analysts noted. Despite the cheese’s lack of quality control measures and inconsistency, the market for Alp Cheese has “big potential”, AlpFUTUR added, “because of its old tradition, its association with nature and mountains and its special sensory and nutritional qualities.”

Choice Market

On a mid-summer day in Bend, Oregon, a town of about 85,000 people in the American Pacific Northwest, Kasia Wilson, a cheese specialist at an upscale grocer, was happy to talk Appenzell. Specifically, canton Appenzell Inner Rhodes and Alp Fählen, a stunningly gorgeous glacial valley pasture squeezed between the Säntis and Alpstein massifs at about 4,200 feet in northeastern Switzerland: this is her adopted dairy.

Some of the European cheeses that make it to Wilson’s store – there are 11 stores in the franchise called Market of Choice – come from large producers like Emmi or Mifroma, an arm of the $28.1 billion Migros group. Her Adopt an Alp order is different. All of the cheese will come from the Inauen family, a team of two adults and four kids, who tend 25 cows on Alp Fählen. A sign scratched in chalk above wedges of Norweigan Jarlsberg reads “We’re adopting!” It mentions the Swiss family and includes a picture of their summer alp. Customers ask about the sign frequently, she says.

“To think the family is out there now, two hours from the closest road, way up in the Alps making cheese for us, I mean, that’s great,” Wilson says. “There’s no way any of us could get this cheese unless we were in Switzerland, in Appenzell, in the fall, with the Inauens.”

Wilson suspects she’ll charge customers about the same for the cheese as she does for other European cheeses or about $20 a pound (SFr44 per kilogram). Galen LeGrand, a cheese department manager at a small grocer north of Bend in Mount Vernon, Washington, believes he’ll charge less. He adopted five alps that he visited this summer with Hostettler in person.

“You could easily sell this cheese for $44 a pound but I’ll make the money I need to make on mozzarella and cream cheese and try to keep the Adopt-an-Alp cheese below $20,” he says. “The education is more important to me. Farmers all over have the same struggles and cares and hopefully ethics. The blood sweat and tears that go into this cheese: people often don’t realise that when buying an end product.”

And are Swiss grocers and restaurants ready to adopt American dairies? “I wouldn’t,” Wilson jokes. “If I had all the cheese they do I wouldn’t look anywhere else.”

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.