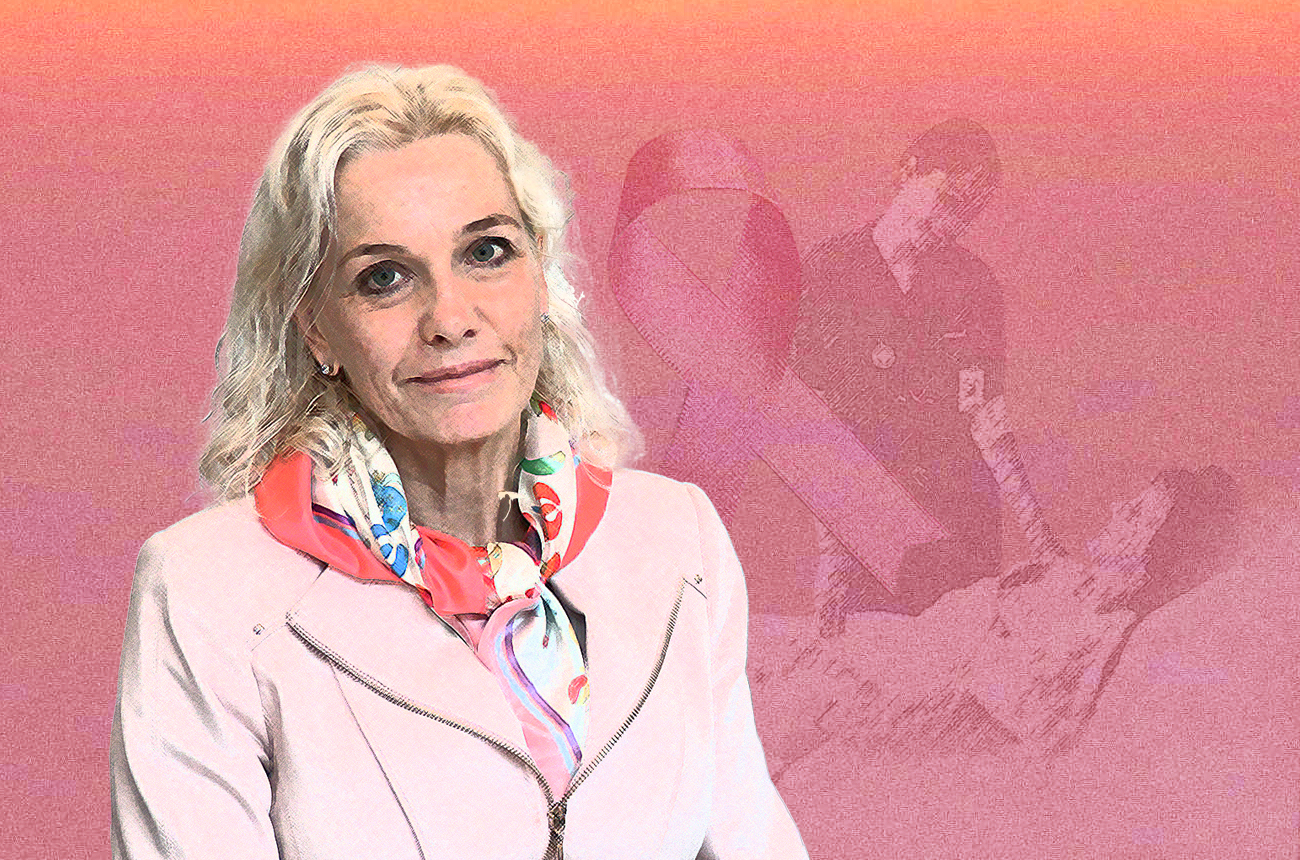

Pamela Munster, ‘From cancer doctor to cancer patient and back again’

Born in St Gallen, Pamela Munster recounts her battle against cancer in a poignant book published in 2018. A world-renowned oncologist, she has been working in San Francisco for 15 years - and now feels very much at home there.

“I didn’t choose California, California chose me,” Munster says. When she was appointed by the University of San Francisco, she already had an impressive career as an oncologist behind her. She trained in medicine in Bern, and had been practising for several years in Florida, having previously spent time in Indiana and Manhattan, which left a “trace of urban America” in her. What about the Bay Area, with its mists and Mediterranean climate? That had “never been in her plans,” she says. But never say never. And the challenge in a job that combines her two passions – research and patient care – motivates her.

In San Francisco, she discovered that fate had a stroke of bad luck in store for her. In 2012, at the age of 48, Munster was diagnosed with early-stage breast cancer. Her response was swift and professional: a preventive double mastectomy, followed by reconstructive surgery, then removal of the ovaries – also as a preventive measure. She had discovered that she carried a nasty mutation of the BRCA geneExternal link which increases the risk of cancer.

“It shattered my sense of immortality,” she says. “Not that I believe myself to be immortal, but in general, we don’t think about death every day, do we?” It has also changed her relationship with her patients. But she doesn’t mention her cancer during consultations, except when she thinks it might help them. “They don’t come to see me to hear about me,” she says. “But if someone says something like ‘you don’t know how bad I feel,’ then I can say ‘Yes I do’.”

For a full version of the interview, listen to our podcast the Swiss Connection.

So many destinies

A few years after the ordeal, a friend suggested that she tell her story in a book. “At first, I thought I’d never have the time, but he put me in touch with an agent, and guess what? I did it,” she says. Reading these 260 pages, it’s clear that the aim was not to exorcise the demon that had threatened to devour her. She wanted “to give people an insight into what it’s like to have cancer, and to remind them that there is always hope.”

Published in 2018, Twisting FateExternal link does not focus on the author herself, although her story is the common thread. It follows the journeys of many of her patients – most of them women but also her father, who died of pancreatic cancer six years after being diagnosed. In fact, the main character is cancer itself, which is so multifaceted that virtually every case is unique.

Silicon Valley and Switzerland are both considered among the most innovative areas in the world. Why? What divides them and what brings them together? What can they learn from each other? In this series, we tell you about Silicon Valley through the eyes of the Swiss who experience its temptations, promises and contrasts up close.

Without pathos or voyeurism, the writing is clinically precise, with the necessary discretion when it comes to dealing with the most intimate details. The whole book is permeated by the empathy the doctor shows in her relationships with her entire staff, her family and, of course, her patients.

But not all their stories have happy endings.

“I have finally managed to forgive myself for not being able to save everyone,” she writes towards the end of the book. “When you start out in medicine, you really hope to be able to cure and save people from disease,” Munster says. But, of course, no one ever fully succeeds. Especially with cancer. “You can’t be a good oncologist without having a deep, personal and emotional connection with your patients. And that requires the ability to not blame yourself if a treatment fails.”

Beating cancer

But Munster continues to believe that medicine, through “creative approaches,” can beat cancer. “Not cure it exactly but make it a treatable disease that you can live with, like AIDS,” she says.

That is the direction of her multiple research activities, at the University of San Francisco, but also at Alessa TherapeuticsExternal link, the start-up she founded in 2018. Alessa produces implants that deliver treatment directly into the bodies of prostate cancer patients. Two clinical trials are underway (in the US and Australia/New Zealand) and a third is in the pipeline. “We’re not the only ones in this market, but the advantage we have over our competitors is that our implants remain active for two years, compared with six months for the others,” Munster says.

She also sits on various committees for the development of new cancer treatments. She publishes widely and frequently holds awareness-raising conferences in the United States, the United Arab Emirates and India. But even such an energetic, strong-willed woman can’t do everything, and she admits that she hasn’t maintained professional ties in Switzerland.

But she has kept up her personal connections there. “Of course, it’s my family I miss the most here, but also nature and the way the Swiss look after it. And also the food, especially the chocolate,” she admits. Although she returns regularly, Munster doesn’t think she’ll ever live in Switzerland again. Her three children, her husband – also an oncologist – and her life and work are in the United States.

Strength of spirit

What about Switzerland, which regularly tops the world rankings for innovation? She worked there when she was starting out, and describes the experience as “very innovative,” albeit with its drawbacks. In her view, encouragement is lacking. The Swiss mentality pushes people in key positions to ask too many questions like “Will this work?”; “Are you sure you can do it?” or “Why do we need this?”

In Silicon Valley, where she lives, she is not confronted with these questions. “Here, it’s better to have a bad idea than no idea at all, and if it doesn’t work, no one will penalise you, they will just say ‘pull yourself together and try something else.’ Because no one looks at where you’ve come from – instead they look at where you’re going.”

“After working in the Swiss system and the American system, that’s the difference I see,” she says. Her view is that if this spirit of innovation and experimentation were more widespread in Switzerland, the country could easily rise to the level of Silicon Valley. “Because the skills are there, the motivation is there, the money is there. But it’s the mentality that’s not quite there.”

Healthy living

Healthy in body, mind and spirit, as the saying goes. In San Francisco, it seems to inspire many people – including Munster of course. In the morning, runners are everywhere, people do yoga in the parks and those who can afford it try to eat healthily – there are very few overweight people. Cigarette butts, the scourge of European cities, are almost completely absent from San Francisco’s pavements, and with the exception of cannabis enthusiasts – which California legalised in 2018 – it’s very rare to come across a smoker.

Does this healthy lifestyle have an impact on the number of cancer cases in California? “It’s well established that a healthy lifestyle – especially food and exercise – reduces the risk of cancer. And here, we’re starting to see the benefits,” Munster says. On the map of cancer mortalityExternal link in the United States, California is one of the least affected states. With 132 deaths per 100,000 people, it is far behind West Virginia, the stronghold of the tobacco industry with almost 185 deaths per 100,000 inhabitants.

A nature lover, hiker and a keen sportswoman, Munster’s childhood in the St Gallen Alps left her with a passion for skiing and a taste for risk-taking. “My lifestyle puts me in more danger than cancer ever will,” she notes humorously in her book, which begins and ends in the snow. An avalanche could have killed her in Switzerland on the eve of her 20th birthday as would losing her balance in a ravine during a wild descent in Canada in 2018. “But my cancer taught me that you always find help in the end,” she writes. And even if the fear is still there, her story is “about life, not death. A life beyond our fears.”

Edited by Samuel Jaberg. Adapted from French by Catherine Hickley/ac

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.