A ‘neutral’ hub for artificial intelligence in the Swiss Alps

In a new laboratory in Davos, scientists from all over the world are working to develop algorithms with human-level intelligence. The Swiss Alpine city wants to become known as a research hub for “politically neutral” artificial intelligence to counterbalance the influence of China and the United States.

In a historic villa in the centre of Davos, scientists are trying to understand the fundamentals of human intelligence. They are convinced that decoding the brain is the key to developing an artificial intelligence (AI) that serves humanity instead of autocratic governments or big interest groups. In this way, they hope to help solve the biggest challenges of our century, such as climate change and diseases.

Thanks to its status as a neutral country with strong research capacities, Switzerland has the potential to challenge the approaches of China and the United States, which have been using AI to impose their models of power: dictatorship on the one hand and capitalism on the other.

“Globally, we need a third AI research pole that does not function as a corporation or a state-owned enterprise,” says Davos mayor Philipp Wilhelm. “What is missing is a neutral, independent and humanistic approach.”

A centre for neutral AI

Davos, known for hosting the World Economic Forum (WEF) annual meeting, has long been home to renowned research institutes. But until recently, AI was hardly a topic in the valley in southeast Switzerland: it’s been more commonly associated with the much larger cities of Zurich, Lausanne and Lugano. That is until Pascal Kaufmann, a Zurich-based neuroscientist with a passion for ancient languages and philosophy, decided to set up an international laboratory for “human-level” AI research, in Davos. Lab42 opened its doors at Villa Fontana in July 2022.

Both Kaufmann and Wilhelm believe that the Alpine resort, with its 11,000 inhabitants, has the prerequisites to attract talent from around the world and become another Swiss AI hub.

“Davos is a world-leading science city, embedded in fantastic nature,” says Kaufmann. “The air is clean and the infrastructure is top notch thanks to the WEF.”

Video: Davos Mayor Philipp Wilhelm explains how the mountain town developed into a major research hub.

Kaufmann has a self-described “friendly” relationship with Davos. His NGO Mindfire, which advocates for AI that approximates human intelligence, launched its first initiative to crack the code of our brain in Davos in 2018, inviting experts from around the world. A few years later, when his team wanted to turn these initiatives into a laboratory with a physical location and a virtual community, the city welcomed them with open arms.

“The Davos approach is to research the most important global issues,” says the city’s mayor Wilhelm. “Digitalisation is one of them.”

Brilliant minds wanted

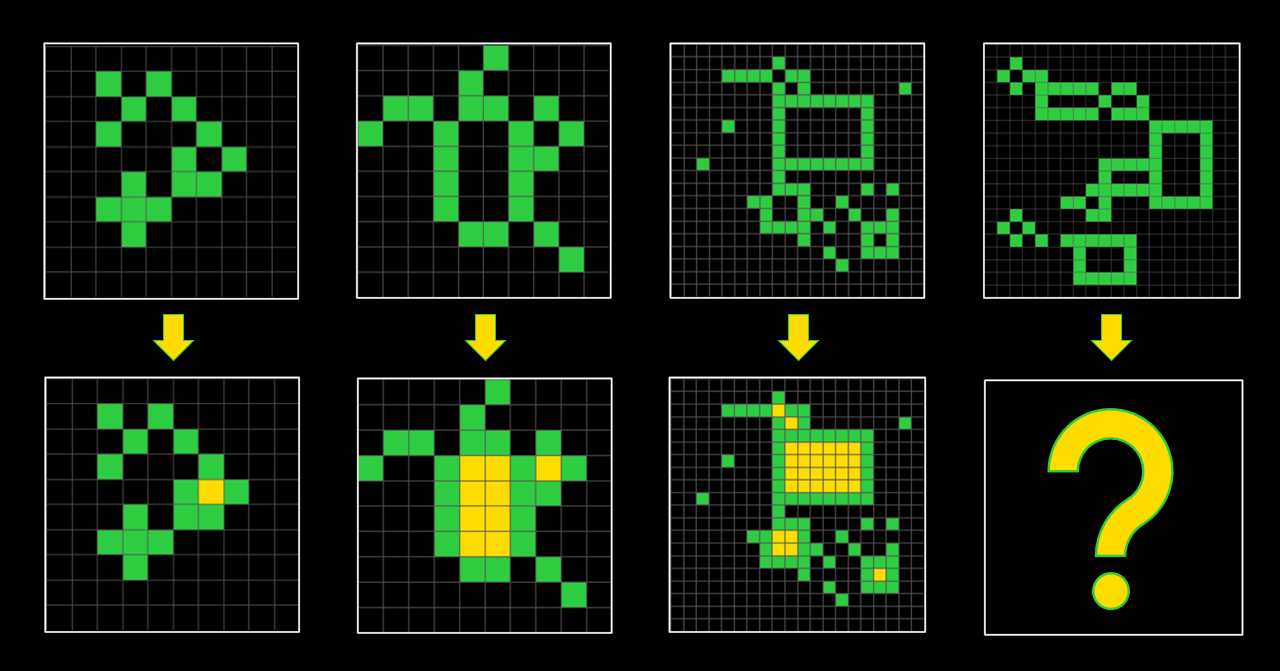

But the network that Kaufmann and his colleagues aspire to build goes far beyond the Alps. Using online challenges in the form of puzzles or multi-level games that current machine learning approaches and algorithms cannot yet solve, the Lab42 team scouts the brightest minds in the field of AI around the world and connects them with each other. An example is the Abstraction of Reasoning Corpus (ARC), a challenge that the French software engineer and AI researcher François Chollet, currently working for Google, created in 2019. ARC is considered an intelligence test for algorithms and consists of 1,000 different tasks, many of which require abstraction capabilities that AI does not have today.

The participants whose algorithms solve the greatest number of tasks win cash prizes and are invited to stay in Davos and contribute to the lab’s research. Around 100 scientists and collaboration partners have visited the lab since July, but Kaufmann says it’s not enough.

“To make a real breakthrough in AI, we need hundreds of thousands of scientists to work together,” he says.

The lab, funded by donations, employs a dozen researchers. Donors include several public institutions, such as Swiss cantons and the municipality of Davos, as well as the manufacturer MaxonMotor and banks UBS and GKB. There are further private backers, but Kaufmann does not disclose their names.

‘Human intelligence is not enough’

So far, the most sophisticated AI-based tools have managed to solve only 20% of the ARC test. For this reason, Kaufmann and his team insist on understanding how the human brain works in order to advance AI in areas such as abstraction and reasoning.

“Human intelligence of individuals is not enough to solve the world’s problems, but that is where we have to start,” he says.

Lab42 has just launched a global competition called the ARCathon II, with the hope of attracting even more talented people to its circuit. “We want to get to the point where we can build robots that can perform some complex tasks, like planting trees to fight climate change, or develop treatments for incurable diseases,” says Rolf Pfister, who heads the lab.

AI tests are not the only means to this end: the lab also held a writing competition, which ended at the end of December, to gather opinions on the principles of intelligence from experts and disciplines with no direct link to AI, such as philosophy, biology, and the arts. The third-place winner was a music student.

“It is precisely this transdisciplinary insight from the outside that is very valuable and provides new ideas,” says Pfister.

According to Pfister, most technology companies rely on the same approaches, such as those used for the chatbot ChatGPT, despite their inherent limitations. Since its launch in November last year, this technology – capable of simulating and writing human-like interactions – continues to make waves, with tech entrepreneur Elon Musk tweetingExternal link it’s “scary good” and “not far from dangerously strong AI”. But Pfister believes that although ChatGPT delivers impressive results, it lacks any understanding of the world and is therefore unreliable.

This type of understanding is at the heart of human-level and human-centric AI, says Kaufmann. “Once we know the principle of intelligence, Europe will finally be able to make a qualitative breakthrough in applicable human-level AI and compete with China and the United States, which focus mostly on optimising deep learning and brute force approaches,” he says. Kaufmann believes Davos and Switzerland would provide a politically neutral location for the development of responsible, inclusive and democratic AI-based technologies.

Sophie-Charlotte Fischer of the Centre for Security Studies (CSS) at the federal technology institute ETH Zurich also believes that Switzerland can play an important role in the field of AI. Fischer sees Switzerland as a credible host for international AI research and governance initiatives because it is the home of the European headquarters of the United Nations, is one of the most globalised countries in the world, and is neutral and a non-member of the European Union.

However, Fischer, whose research focuses on AI governance and the technological rivalry between the US and China, also says that cooperation on AI has become increasingly difficult as global competition intensifies – as evidenced by the recently introduced US export controls targeting China’s semiconductor industry.

Developing Davos

But Davos, when not overrun by tourists or WEF visitors during the winter season, remains rather isolated geographically. Its mayor Wilhelm says this is no longer a problem in the digital age, pointing out that dependence on large urban centres is decreasing while work-life balance is becoming more important. Davos, with its research institutes, skiing in winter and hiking in summer, offers a good quality of life, he adds.

But the lack of living space, especially for locals and those who come to work, is a worry for Wilhelm.

“We are working intensively on a housing strategy to ensure that in the coming years there will be sufficient housing for families, accessible to people of different income classes,” he says. Davos’ family-friendly policies and job prospects for young generations are close to the heart of 33-year-old Wilhelm, a Social Democrat and one of the youngest mayors in the city’s history.

“We want our young people to also participate in the research progress being made in Davos.”

Edited by Sabrina Weiss and Veronica DeVore

More

The ethics of artificial intelligence

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.