A bittersweet trip: visiting Brussels with Swiss EU fans

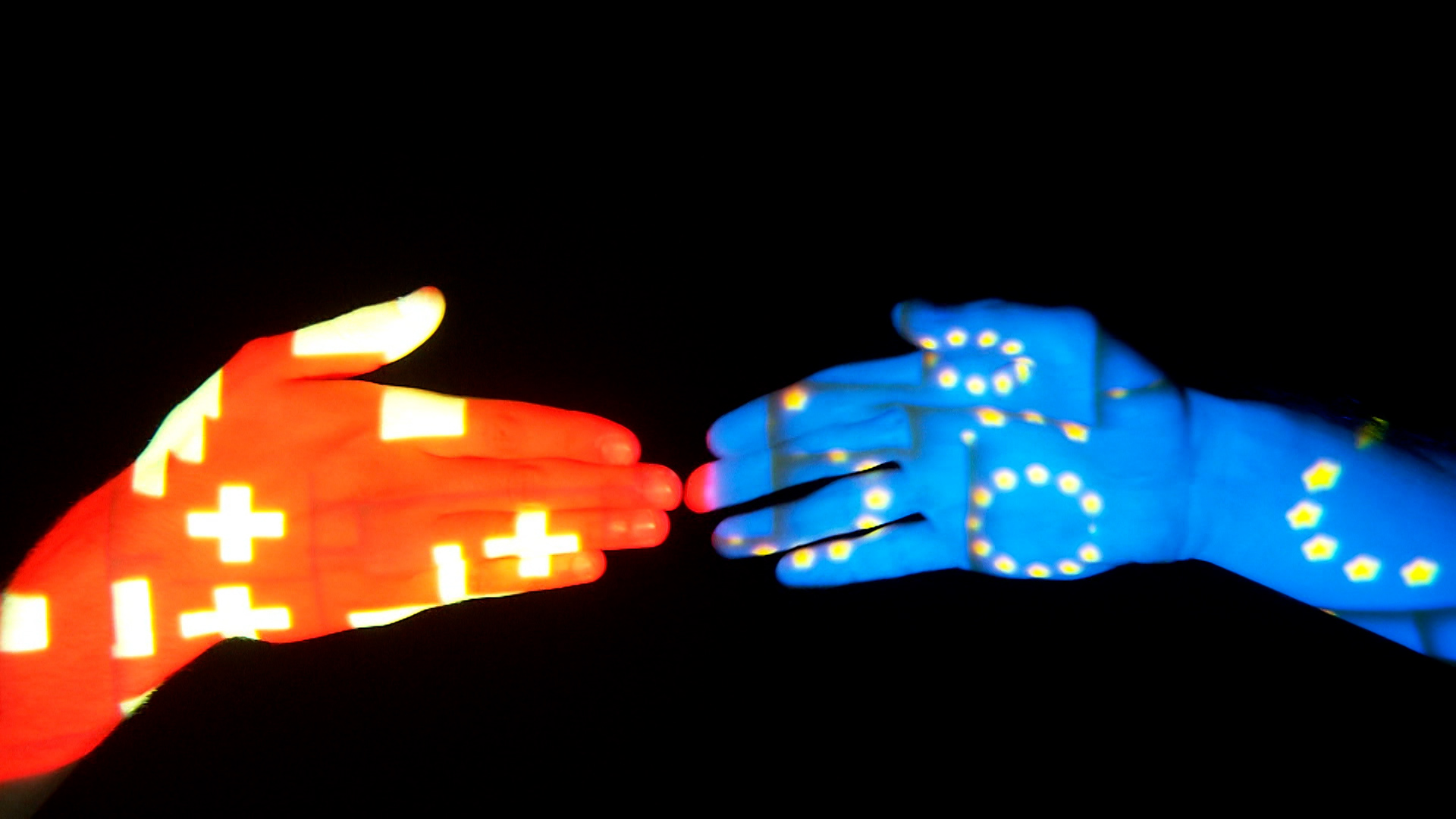

Never has it seemed less likely that Switzerland will one day join the European Union (EU). “Why, though?” asks a group of Swiss pro-Europeans. SWI swissinfo.ch joined them on a five-day tour of Brussels and its institutions.

The trip culminated with a visit to the European Commission. There, the officials showing the group around took the same line as most of the other people met over the week.

Switzerland? Of course it is a member of the European family, but it sure is an awkward one.

What about future relations? Well, comes the reply, that depends entirely on Switzerland, as the EU has long since made its position clear.

Switzerland – the EU staff imply – either does not know what it wants or is deliberately holding back from saying it clearly.

The Brussels officials need not expect any deep-running criticism from the Swiss visitors. On the contrary, there are many nods of agreement within the group. Although they come from Switzerland, the participants have strong sympathies with the EU. The trip was organised by the European Movement Switzerland, which – as the name suggests – is in favour of accession to the EU.

Similar organisations exist in other countries, but few have it as hard as in Switzerland, where joining the EU seems so unthinkable today that nary a politician will speak out in favour of it. “That would be tantamount to political suicide,” says one of the dozen or so participants.

In truth, though, the situation is not all bleak – after all, one of the governing parties, the left-wing Social Democrats, has accession as a long-term goal in its programme. And of the last dozen referendums on EU-related issues, 11 were approved by voters. But a look at the statistics is telling. In 2019, just 6.5% of the 18–34 age group was in favour of joining the EU. In 2021, 19% of the total population aged 15 and over in Switzerland had dual citizenship, and at least half of these had an EU passport. Roughly calculated, then, not even all of them support accession.

Why change anything?

Why does Switzerland not want to think about EU membership? It was not always so. In the early 1990s, numerous voices in politics and society spoke out strongly in favour of it. The group of Swiss pro-Europeans tries to answer this question. Firstly, political parties today lack courage and vision, and the left in particular should be doing more. Also, no one wants to give fodder to the right-wing Swiss People’s Party, which has successfully cultivated the image of the EU as bogeyman over the past three decades. Lastly there is the paradox of the bilateral approach, which has become a victim of its own success. If everything is working well, why change it?

There is broad consensus in the group, however, that things will not simply continue to go smoothly. For years, the EU has wanted to lift its relationship with Switzerland to a new institutional level, so that the country would basically be treaty-bound to take part in European developments, rather than requiring a special regulation each time – which can easily arouse the envy of member states.

The group also agrees that time is not on Switzerland’s side. Brexit has left scars in Brussels, and the EU is grappling internally with right-wing chimeras. The continent’s importance in the world is declining for demographic, political and economic reasons. The war in Ukraine has made both Bern and Brussels painfully aware that they need each other – but also that the EU has far more important things to deal with than a Switzerland that many still see as a cherry-picker. “Our position in Brussels is becoming more and more difficult,” is how one participant sums up her impression, which is echoed by the other members of the group.

Victim of its own success?

Maximum proximity without accession: this seems to be the desired goal for most Swiss. The relationship is often seen as a commercial and purely technocratic one. This is exactly what Swiss Foreign Minister Ignazio Cassis said (“The EU Commission works technocratically”), when he ruffled his interlocutors’ feathers in a newspaper interview in 2021 – for Brussels does not appreciate comments of this kind.

There never was a European dream in Switzerland, even though Winston Churchill gave his groundbreaking “Europe speech” in Zurich in 1946. Elsewhere, European integration is seen as a peace-promoting mission with a metaphysical component. The experiences of the 20th century have clearly revealed the alternatives: in the Balkans in the 1990s and now again in Ukraine. Switzerland, meanwhile, is one of the few European countries that has suffered no historical ruptures over the last century. So joining the EU is seen not as a historical inevitability, but as one option among many.

And Brussels has in large part gone along with this, treating Switzerland as the special case that it likes to see itself as. “A democratic country, governed by the rule of law, neutral – Switzerland is never going to be a problem in Europe,” comments someone in the group. But times are changing.

Since the Russian attack on Ukraine, Switzerland’s long-cherished neutrality – an identity marker that helps build national cohesion – has been increasingly perceived as opportunism. The country’s refusal to authorise the export of Swiss-made weapons to Ukraine caused much ill-feeling. Just how reliable is a partner who also wants closer ties with NATO structures but does not guarantee loyalty in an emergency?

People in Switzerland often warn about mixing different, seemingly unrelated issues. But the supposedly technocratic EU officials often understand politics more holistically than is the case in Switzerland.

What next?

The trip is drawing to a close and we have a last lunch together – typical Belgian fries and strong local beer. The group looks back over the past week: they have learned a lot about the workings of the different EU institutions and talked to lobbyists, NGOs, trade unions, politicians and diplomats. The weather was – by Belgian standards – exceptionally good overall, and even now the sun is shining. A Babel of languages, also typical of Brussels, rises from the busy square in front of the restaurant.

The participants leave Brussels with a bittersweet feeling. Most of them have worked and lived abroad and are committed to Swiss cosmopolitanism. They see themselves as being on the right side of history, as politicised people do. In Brussels, they received the affirmation that is largely lacking at home. In all their visits, the Swiss EU fans were well received. They were repeatedly told that Switzerland would be welcome as an EU member.

They know for sure that this will not happen in the near future. So what is the path ahead for pro-Europeans in Switzerland? Some are content just to lament (“This country has no vision for the future!”), while others are calling for a referendum to push the government to “finally move forward – even at the risk of failure!”

Despite the group’s enthusiasm and dedication, what is perhaps Switzerland’s most complex political question today will clearly not be resolved on this trip either. The official visit is now over. The participants make their farewells – some are heading straight back to Switzerland, others are staying longer in Brussels, while others still are travelling on elsewhere. After a few minutes, the small group of Swiss EU supporters has vanished in the crowd.

Edited by Balz Rigendinger. Translated from German by Julia Bassam.

More

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.