A life devoted to chimpanzees

Swiss-born Daniel Hänni has spent most of his adult life working with chimpanzees. As part of his efforts to protect them, he has dedicated the past 15 years to restocking the forests of Uganda.

Hänni from the northern Swiss canton of Thurgau has been fascinated by primates since he was a child, when he would scribble the names of different species of marmosets on his pencil case. He spent hours observing chimps in zoos and reading articles about the famous British primatologist, Jane Goodall. Asked why he was so obsessed with primates, he replied, “I think it’s because they are so human-like.”

He now runs the Jane Goodall Institute Switzerland External link(JGI Switzerland), which he set up in 2004. It aims to promote the protection of great apes and their habitat. He also organises tourist trips to Uganda to visit the natural habitat of chimpanzees. Funds raised are used for conservation.

A chequered career

Becoming a professional anthropologist was not straightforward for Hänni. A powerfully built man, now in his fifties, he was previously a Swiss national athletics champion – in 1992 his Winterthur team won the Swiss championships in Olympic relay. He was also a 400-metre champion for canton Zurich. He trained extensively for the track while also doing an apprenticeship as a draftsman, which led to a job in real estate. It was at the age of 26 that Hänni took the plunge to live his passion in full. He left his job and went back to school to qualify for a degree course in anthropology.

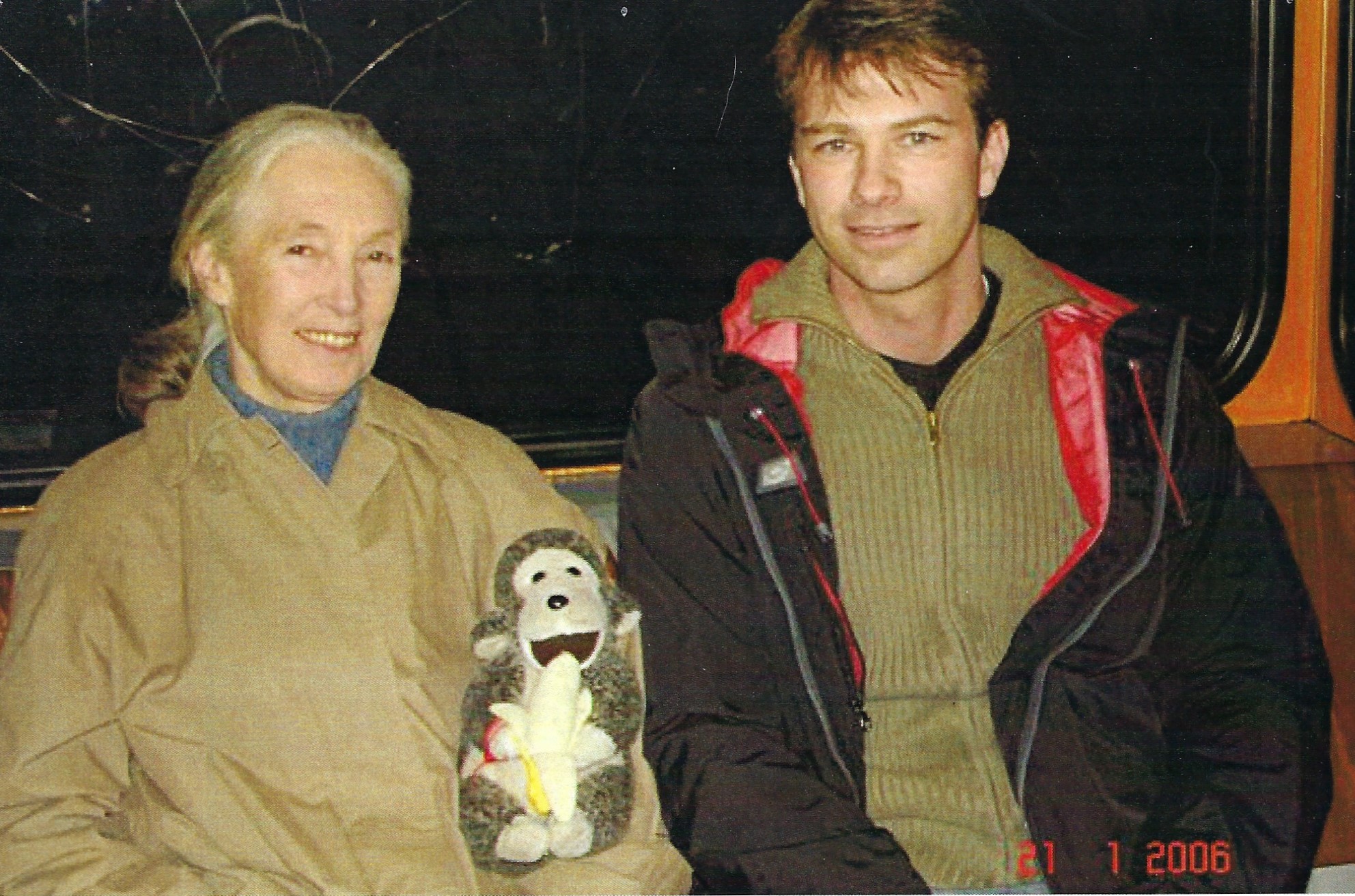

He was then qualified to set up the Swiss branch of the Jane Goodall institute. In the application process he was finally able to meet the British primatologist.

Kindred spirits

“She said she was impressed with my CV, and had expected to meet a much older man,” recalls Hänni. “She’s a kindred spirit.” A long-lasting friendship ensued, evident in the many photographs he shows us of the pair together.

It was she who inspired him to pursue the conservation work that catapulted him into the next chapter of his professional journey: the jungles of Uganda.

In 2006, Hänni visited an anthropology conference in Uganda to identify problems chimpanzees were facing in the Albertine Rift Valley, a 1,200 km-long valley in central Africa that is prime territory for primates. A chimpanzee census carried out from 1999 to 2001 revealed that chimpanzee populations were in decline due to loss of habitat from deforestation.

When the JGI Uganda made a plan to reconnect scattered ape communities through reforestation, Hänni volunteered to participate in a new ape count as groundwork for the conservation work. After attending a course at St. Andrews University to learn how to carry out a proper scientific census, Hänni was put in charge of the JGI Uganda project.

Swamps, posho and beans

All of Hänni’s romantic ideas about working with chimpanzees were quickly dispelled. It was a challenging 18 months. Hänni and his team of international researchers and local assistants scoured the forests, not for chimpanzees, which tend to make themselves scarce, but for the sleeping nests that they build daily in the trees. The quantity of nests they leave behind provide insights into the density of the colonies.

“We walked between seven and 21 kilometers each day. Sometimes the forests were flooded, so I would take my boots off to keep them dry and wade barefoot, but you had to look out for thorns in the streams,” Hänni recalls.

He continues: “When we had to reach transects deep in the forest, we would pitch our tents there. We always kept two people in the camp to protect it from wild animals, illegal hunters or loggers. We were often covered in ants and had to eat the same diet of posho and beans for days on end.”

The results of the survey were sobering: the numbers of chimpanzees had declined since the last census. Hänni set out to work with the local population to protect their habitat.

Information collected by Hänni’s team and a subsequent census ending in 2017 demonstrated a continued decline in the chimpanzee populations of Uganda. In the western Wambabya forest, populations decreased by 22.5% between 2000 and 2008, and 31% between 2008 and 2017. The central Bugoma forest revealed a similar picture ( 34.5% and 28%). The decline is due to deforestation and urban growth.

Local knowledge

This was the start of Hänni’s love affair with the country and its people. “I wanted to get to know them, to find out what made them tick,” he says. He realised that conservation work would be impossible without cooperation. He met and married a local woman, Carmen, the mother of his two children. They lived in Kigaaga, close to the forest, sharing a house with a teacher and research assistants.

“If I hadn’t lived with the people and got to know their culture, I imagine I would have made many, many mistakes,” he says.

Hänni was the only white resident in the district. “When I was walking with my assistants in the town and saw a white person, I wondered what they were doing there, forgetting that I was also white.” They remained in Uganda for two years, during which Hänni commuted between his house and the forest.

Hänni’s approach was to reverse the effects of deforestation and plant millions of trees, thousands of which, he soon found out, were stolen as the project progressed.

“We planted a big nursery and noticed that thousands of trees were stolen during the night and resold elsewhere, so we set up smaller nurseries on the farmers’ land,” he says. “Now, several thousand farmers are involved, and they receive new trees every year.”

Some trees are planted specifically to provide building materials, so people do not fell the forest trees where the chimpanzees live.

There were other reasons for deforestation. “In one forest we noticed trees were only felled when parents had to pay school fees,” Hänni says. “We found those families and paid the school fees for them. But in return, they have to plant trees. This is how we saved this forest”.

JGI Switzerland has helped to fund the planting of over 5 million trees in a corridor between Budongo and the Bugoma Forest. In 2009, the institute funded the establishment of an education centre for children in Kigaaga. The centre works with 10 schools with over 4,000 children in total and explains the conservation projects.

Conservation tourism

One way to make his project sustainable was to launch eco-tourism projects. These would generate income for conservation of the forest. This venture was not without its critics.

“I often receive emails from people who say the animals would be better left alone,” Hänni says. “It would be great if we could just leave forests as a protected places but if we don’t go there with tourists, then the local people can’t protect them. They don’t have the money, and neither does the government”.

Hänni returned to Switzerland in December 2012 and now lives with his family in Homburg, a small village in canton Thurgau. The former draftsman designed and partly built his wood and clay house. But he has not completely left behind his former life in Uganda. He leads about four safaris there per year with small groups of Swiss visitors.

To date, Hänni has taken more than 250 clients on small group tours of Uganda and about 80% of them have contributed to projects that promote wildlife and chimpanzees. Hänni also has his own business, Africa Wild AdventuresExternal link, which organises trips to track chimps and gorillas. He is still invested in the Albertine Rift Valley and is optimistic that his corridor project will reach fruition.

“We must work with communities and show them that humans and chimpanzees can live together,” he says. “If people see that their livelihood is improving because of chimpanzees, there is a good chance that the apes will still be there in 20 years.”

The Ugandan tourism ministry says visitors bring in an estimated CHF1.29 billion ($1.4 billion) annually. Joshua Rukundo, executive director of the Chimpanzee Sanctuary and Wildlife Conservation Trust in Entebbe, Uganda, says, “A lot of this revenue has gone into the development of the national park, and enforcement of wildlife and park protection”.

The Swiss Jane Goodall?

Despite more than 15 years dedicated to the conservation of chimpanzees and their habitat, Hänni rejects the moniker “The Swiss Jane Goodall”.

“I just had a dream as a child to live in the jungle, climb trees and protect the animals and the forest,” he says.

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

Join the conversation!