A weapon against superbugs lies in the Rhine River

Antibiotic resistance is a growing public health risk. A unique collection of beneficial viruses, called bacteriophages, gathered in Switzerland is helping researchers around the world to develop new therapies against incurable infections.

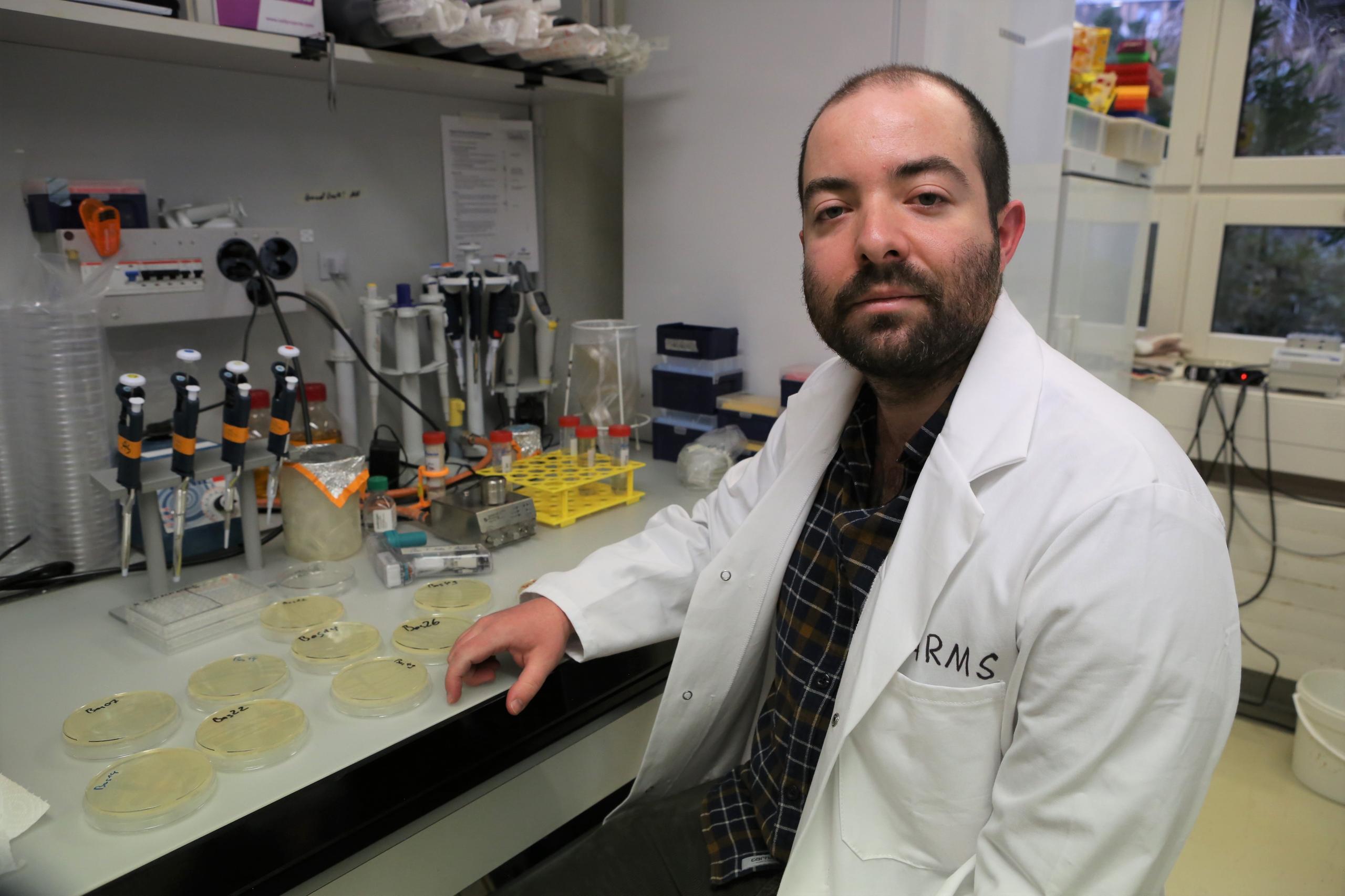

Talking about beneficial viruses after having just emerged from the Covid-19 pandemic may seem like a paradox. Yet not all viruses are harmful to our health. Those that infect bacteria, called bacteriophages or simply phages, can prove very useful and save lives, argues microbiologist Alexander Harms. However, little is known about them. “Studying them is like exploring the dark side of the moon,” he says.

It’s a mission into the unknown that he launched in 2019 together with a group of high school students. During a summer course in Basel, Switzerland, they collected samples of bacteriophages occurring in nature and determined their key traits. Today, these viruses have become an important resource for research institutes around the world and could help in the treatment of bacterial infections.

Killers of bacteria

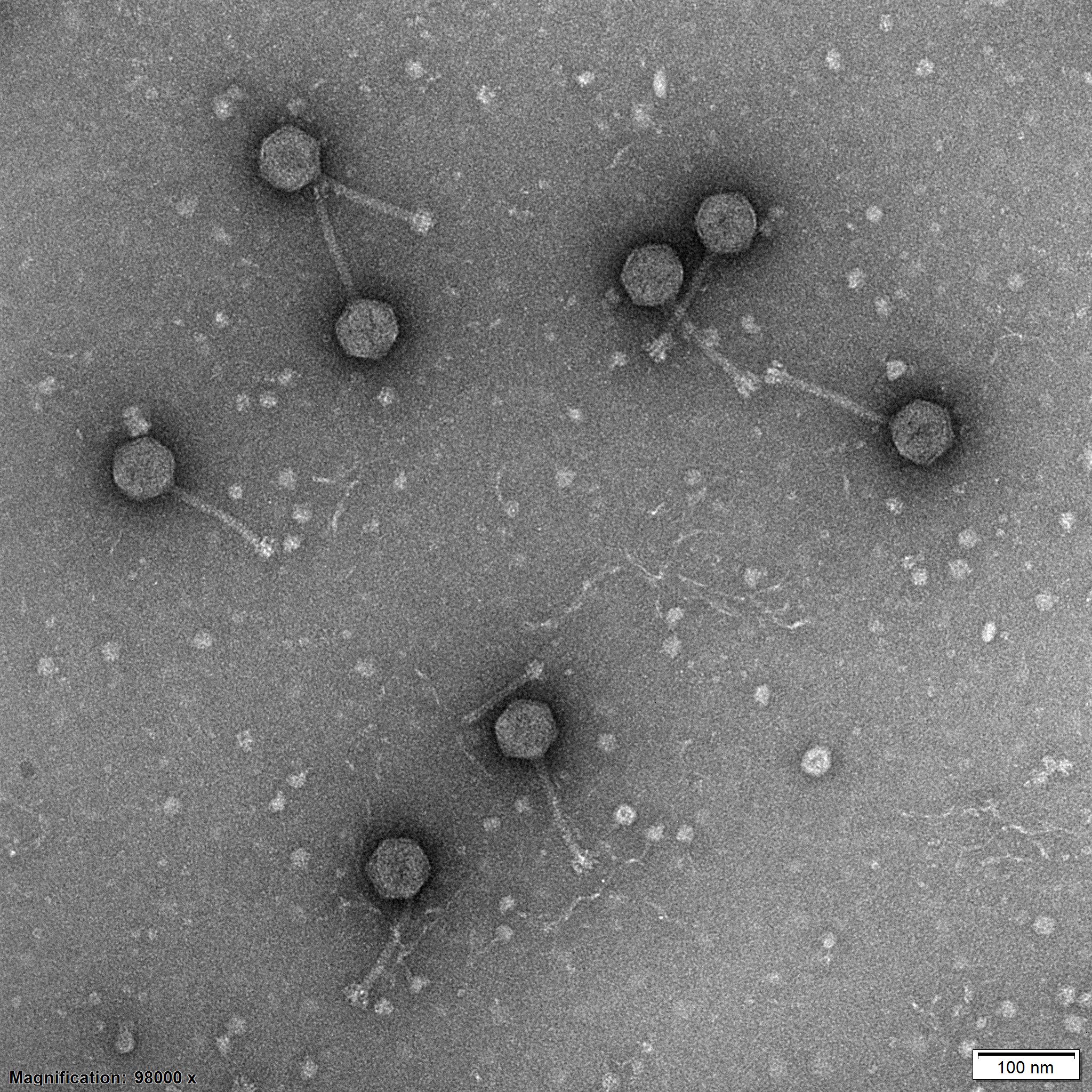

Phages, like all viruses, cannot replicate on their own, but must exploit the metabolic apparatus of the bacteria they infect. After replication, phages induce the death of their host by rupturing the cell membrane (cell lysis).

Phages number in the trillions and are found in virtually every ecosystem on Earth, from the forest floor to the surface of the ocean. They play a pivotal role in the carbon cycle contributing, for example, to the spread of nutrients contained in marine bacteria thanks to their lytic activity. “They are among the driving forces of our planet,” says Harms, who until last year worked at the BiozentrumExternal link of the University of Basel, an institute specialised in molecular and basic biomedical research.

Phages are also present in our bodies. Fortunately, they don’t attack human cells, but they can have an effect on the composition of the bacterial community. However, their impact on the gut microbiotaExternal link is still poorly understood.

The ability to selectively infect bacteria – a phage recognises a certain species of bacterium and often only certain strains of that species – makes them extremely interesting research tools, according to Harms. Phages can destroy bacteria that have contaminated food, such as salmonella, or be used to treat bacterial infections affecting the urinary or respiratory tracts.

And it was precisely the interest in phages, which attack the so-called “sleeping bacteria” responsible for chronic infections, that prompted Harms to equip himself with test tubes and go in search of bacteriophages in nature.

New bacteriophages in the waters of the Rhine

In summer 2019, Harms and a group of high school students collected water and soil samples in the Rhine, garden ponds, compost bins and sewage treatment plants in and around Basel as part of the Basel Summer Science Academy, a course organised by the Biozentrum. “We didn’t know what to expect,” Harms recalls.

In the laboratory, his team then isolated many bacteriophages that infect Escherichia coli – one of the most widespread intestinal bacteria, which can also cause serious diseases – and detailed their characteristics. The result, published two years later in the scientific journal PLOS BiologyExternal link, was a collection of 70 phage types.

The collection confirms that similar groups of phages have the same function all over the world, from China to the United States. “This really surprised me,” says Harms.

Most importantly, the collection reveals the diversity of phages capable of infecting E. coli, says Harms. There are larger collectionsExternal link elsewhere with hundreds of phages, but none characterises them as systematically as the one in Basel, says Harms.

The collection will also be useful for researchers abroad who want to use phages to treat bacterial infections, as an alternative to antibiotics. For example, phages have already been shown to be effectiveExternal link against bacteria that infect ulcers and chronic wounds in people with diabetes, which often lead to amputations.

The revival of phages in medicine

The idea of using phages as a medical treatment – to be administered intravenously or as aerosols – emerged in the early 20th century, especially in the former Soviet Union. During the Second World War, phages were used to treat soldiers suffering from dysentery, an inflammation of the intestines causing bloody diarrhea. However, with the advent and spread of antibiotics following the discovery of penicillin in 1929, the research into these beneficial viruses took a back seat, at least in the West.

But as antibiotic resistance increases everywhere in the world, infections such as pneumonia or tuberculosis are more difficult to fight. Antibiotic resistance is responsible for the deaths of more than 1.2 million people worldwide, more than those caused by HIV or malaria, according to a studyExternal link published in 2022.

The World Health Organization (WHO) now considers antimicrobial resistance one of the biggest threatsExternal link to global health security. The number of deaths could rise to 10 million per yearExternal link by 2050. Western countries have also intensified research on phage therapies, as they promise essentially no side effects and few risks.

Same requirements as all other medicines

But although there is a lot of talk about it, the therapeutic use of bacteriophages is not yet so widespread, as Harms points out. The process of identifying the bacteria responsible for an infection and selecting the right phage to kill it can be complex and expensive. Phages can be susceptible to the body’s immune reaction or, like antibiotics, can induce resistance when administered repeatedly

A bacteriophage is complex. Unlike an antibiotic with well-defined and stable properties, which is thus replicable, a bacteriophage can undergo mutations. This characteristic makes it difficult to obtain authorization for therapeutic use. “If used for therapeutic purposes, phage preparations must meet the same requirements as all other medicines,” says Lukas Jaggi, spokesperson for the Swiss drugs regulator Swissmedic.

“So far, no such preparation has been authorised in Switzerland. A clinical trialExternal link was launched in 2015 and it cannot be ruled out that some doctors have used phages from abroad to treat infections in isolated cases,” Jaggi adds.

From the Rhine to Australia

Even though Harm now works at the federal technology institute ETH Zurich, he hopes the Basel collection of phages will stimulate more research into effective therapies, not only in the human field: “They could prove useful in the fight against bacteria that destroy plantations,” he says. For example, phage preparations could be sprayed on olive groves that are infested with Xylella fastidiosa, a bacterium that is killing thousands of plants in Apulia, Italy, or on apple and pear plantations in Switzerland affected by “fire blight”.

So far, more than 40 laboratories around the world have requested phages from the Swiss collection. Harms does not know whether they have saved any human lives or plants, as the relevant studies have not yet been published.

However, he says that it is a special feeling to know that the phages collected in the Rhine at Basel with limited financial resources are now being used for research projects in places as far away as Australia or the US.

“I want to share our phages with all interested people everywhere in the world. That’s how science works,” he says.

Edited by Sabrina Weiss

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.