Alien spiders in Switzerland – how worried should we be?

This autumn media reports and social media posts about the rapid spread of so-called Nosferatu spiders have caused unease throughout Switzerland. But scientists say the threats posed by such non-native spiders– and other invasive species – are largely misunderstood.

Every autumn it’s the same: when temperatures drop outside, spiders are increasingly drawn into people’s homes, where they seek shelter and warmth. Frightened residents who notice them on their walls take photos of the cold-blooded animals and share them on social media. Then Wolfgang Nentwig’s phone starts ringing.

“This is about the 20th request from journalists since September and shows the big interest, but I’m not sure if this interest is justified,” says the ecologist, somewhat frustrated, when I reached out to him in November. My interview request was prompted by the sighting of an unfamiliar brown spider on my refrigerator door, with legs up to eight centimetres long. Its black abdominal markings bear a resemblance to the face of the vampire from the 1922 German silent film Nosferatu, which gave the spider its common name.

Originally from the Mediterranean region, the Nosferatu spider is now widespread in Switzerland and has made headlines in the local press this autumn, for example “Unidentified spider causes guesswork”, “Nosferatu spiders lurk on the ceiling” or “Five centimetres with poison claws – Nosferatu spider spreads in Switzerland”.

This video, originally posted on TikTok by Swiss commuter newspaper 20Minuten, shows the spiders as spotted in people’s homes:

@20minutenExternal link Die Nosferatu-Spinne breitet sich in der Schweiz aus #20minExternal link #newsExternal link #fypExternal link #spinneExternal link ♬ Originalton – 20 MinutenExternal link

Expansion in Switzerland

“It looks like a media hype with a lot of half-right information and much exaggeration,” says Nentwig. As a professor emeritus in community ecology at the University of Bern and president of the Association for the Promotion of Spider ResearchExternal link, Nentwig has been observing the presence of Nosferatu, or Zoropsis spinimana, for more than 30 years.

He points out that Zoropsis spinimana has been in central Europe for a while, having first been sighted in the Swiss city of Basel in 1994, followed by in Austria in 1997 and in Germany in 2005. The species continues to spread northward with confirmed sightings in Cologne, Hamburg and Berlin as well as in Belgium, the Netherlands and southern England, adds Nentwig.

The spider can primarily be found at lower altitudes in Switzerland, especially in cities and at sites along the north-south traffic axes, according to one report from 2013.External link The spread of such non-native species is often attributed in media reports to climate change, which may well allow spiders to establish themselves in regions where they were previously unable to survive and reproduce. But Nentwig points out that a clear distinction must be made between natural spread and unintentional spread by humans.

“Natural spread, which is only a bit enhanced by climate change, is a normal process,” he says. Since spiders move at best about one kilometre per year, the natural range of a spider species usually increases in small increments, Nentwig adds. But by hiding in packaged or boxed goods on trucks, for example, a spider species can double or even triple its range within a few years.

“We expect the settlement of new spider species in Switzerland will accelerate immensely with increasing global trade,” says Nentwig.

Spiders: elusive and hard to track

Very little is known about the spread of alien arachnids in Switzerland compared to other classes of animals, according to the Swiss Federal Office for the Environment (FOEN). Mites, daddy longlegs and pseudoscorpions are not even recorded by the national database Infospecies.External link This is mainly because the habitat of spiders and other arachnids is so scattered and difficult to track, unlike in the case of quagga musselsExternal link or Asian clams, for example, which are easier to monitor in the closed waters they colonise.

More

Lake invaders: alien shellfish trouble Swiss waters

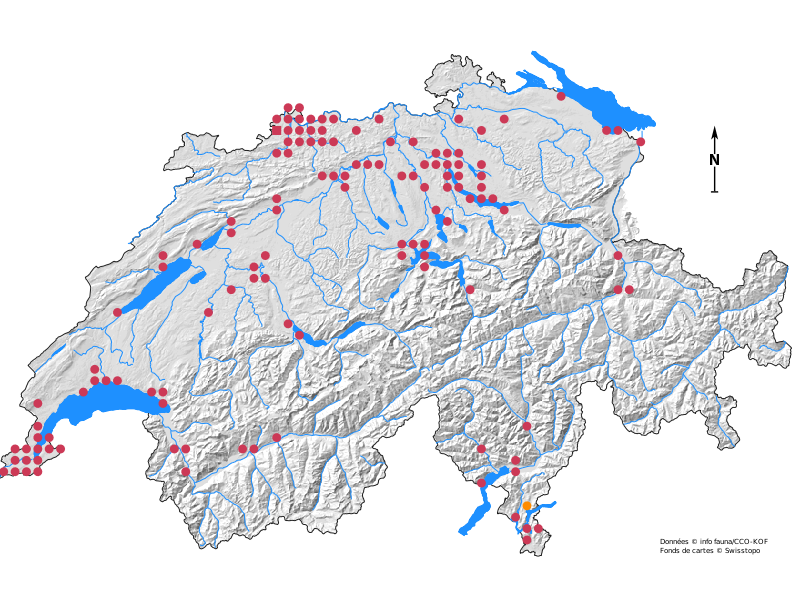

The Swiss Centre for Cartography of Fauna (CSCF) monitors the spread of certain non-native spider species in Switzerland for the FOEN. Based on sighting reports from researchers and members of the public, the Neuchâtel-based centre has drawn up a distribution map for Zoropsis spinimana that documents who saw it where and when.

In its latest reportExternal link on alien species, FOEN states that 11 types of spiders are considered well established in Switzerland, but none of them are currently defined as “invasive” or detrimental to the local environment. “Much more information and data are required to gain a more complete picture of alien arachnids,” FOEN spokesperson Nicolas Gurtner wrote in an email.

Good or bad ‘immigrant’

The presence of an alien species in an area does not necessarily mean that it causes harm. If an alien species displaces native species, interbreeds with it or causes considerable economic damage to agriculture or forestry, it is considered “invasive”. Typical examples are the Marmorated stink bugExternal link and the cherry vinegar fly, which originated in Asia and have infested many plant species across Switzerland and elsewhere.

Invasive species are on the agenda of the COP15 summit in Montreal this month, where delegates from nearly 200 countries are negotiating global measures to prevent and reduce the rates of introduction and establishment of invasive species by 50%, and to control or eradicate such species in order to reduce their impacts on native ecosystems.

For Switzerland, only partial information is available on the damage caused by invasive alien species. A 2019 report from FOEN,External link based on estimated costs for the entire EU region, estimates that the annual damage in Switzerland amounts to approximately CHF 170 million ($183 million).

Invasive alien species capable of causing extinctions of native plants and animals are indeed a serious threat to biodiversity. But recently, a research team led by the University of Geneva and Brown University in the US argued in an opinion articleExternal link that the potential benefits of non-native species should also be considered for a more balanced discussion.

“Long-standing biases against non-native species within the scientific literature have clouded scientific process and hampered policy advances and sound public understanding,” says Martin Schlaepfer, a senior lecturer in environmental sciences at the University of Geneva.

Schlaepfer gives the example of a non-native plant called goldenrod (Solidago gigantea), which has spread near the city of Geneva. It has displaced native plants on a local scale and thus is considered invasive in Switzerland. But it is also appreciated for its ornamental and medicinal properties, and it serves as a food resource for local insects.

When it comes to the alien spiders that are alarming so many Swiss residents, “so far, we haven’t seen any damage they caused to native animals, ecosystem or local biodiversity serious enough to require any measures to prevent their spread,” says Gurtner of the FOEN.

In August an international group of researchers published a studyExternal link on the depiction of spiders in the media. To do this, they analysed newspaper articles from 2010 and 2020 in 15 countries, not including Switzerland. The researchers checked for factual errors and counted the use of emotionally charged words, including “devil,” “killer,” “nasty,” “nightmare” and “terror” in each article.

They found that 47% of articles contained errors and 43% were sensationalist, which are intrinsically more likely to elicit emotional responses.

“One of the most remarkable aspects of modern human-spider relations is the prevalence of arachnophobia in places with few or no highly dangerous spider species,” the authors wrote in the paper.

There might even be benefits to involuntarily offering Zoropsis spinimana a temporary shelter in our homes during the cold months, according to Nentwig. The spider will eat anything that it can overpower, including mosquitoes, houseflies, other spiders, vinegar flies, cockroaches and carpet beetles.

“We have the choice: learn to live with them and accept the spiders’ free service, or struggle with pests if we eliminate the spiders,” says Nentwig.

More

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

![The four-metre-long painting "Sonntag der Bergbauern" [Sunday of the Mountain Farmers, 1923-24/26] had to be removed by a crane from the German Chancellery in Berlin for the exhibition in Bern.](https://www.swissinfo.ch/content/wp-content/uploads/sites/13/2025/12/01_Pressebild_KirchnerxKirchner.jpg?ver=14ffbad8)

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.