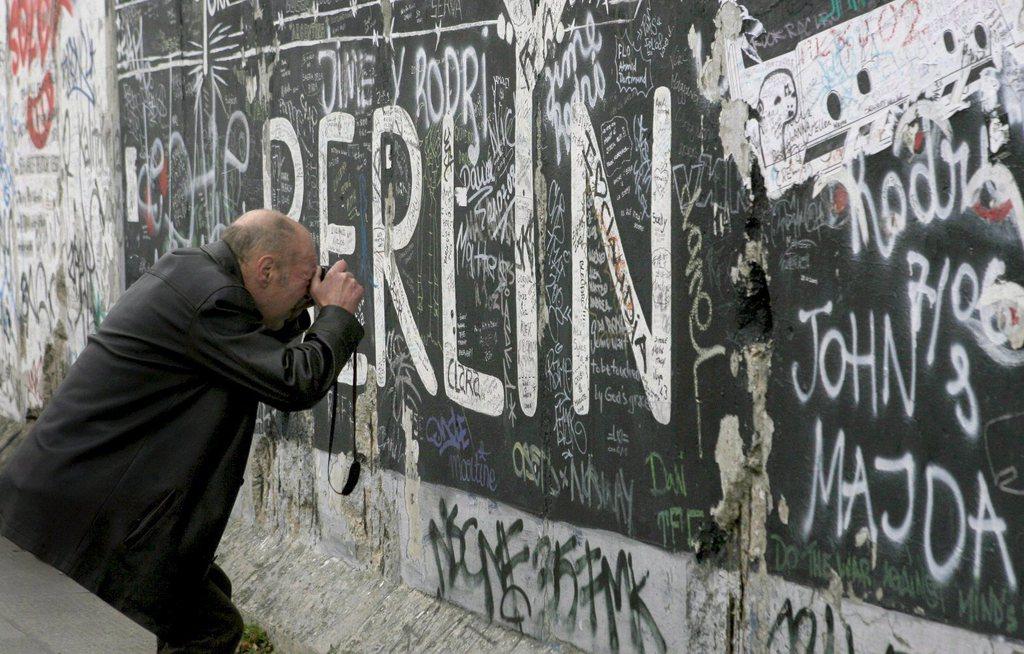

Trumpism as a stress test for democracy

Swiss immigration curbs, Brexit, and now Donald Trump. A series of populist anti-globalism shocks is a test for Western democracies.

Trump’s stunning ascent to the White House is the clearest signal yet of an anti-establishment revolt unfolding in major democracies, stretching across the Atlantic.

The vote to propel Trump to the US presidency reflects a profound backlash against open markets and borders, and the simmering anger of millions of blue-collar white and working-class people who blame their economic woes on globalisation and multiculturalism.

“There are a few parallels to Switzerland – that the losers of globalisation find somebody who is listening to them,” said Swiss professor and lawyer Wolf Linder, a former director of the University of Bern’s political science institute.

“Trump is doing his business with the losers of globalisation in the US, like the Swiss People’s Party is doing in Switzerland,” he said. “It is a phenomenon which touches all European nations.”

Trump’s populist and polarising campaign – an outsider in his own political party – reflects a growing political polarisation that plays out as rejection of the traditional political classes.

His vow to shake up the establishment echoes populist candidates in European countries such as Switzerland, Austria, France, Hungary, Poland and Sweden, where populism has gained despite economically stable conditions.

Listening to people

European and US elites are out of touch with workers, Linder said, because they have been “too much in the hands of big industry and all these clientele who have experienced the advantages of migration”.

And as a staunch defender of direct democracy, Linder sees it as a tool that Swiss voters turned to in 2014 to approve anti-immigration curbs that keep Switzerland, a non-EU state, at arm’s length from the bloc and its policies.

“As long as the ruling elites do not compensate the losers of globalisation, there will be a growing protest potential. And I think the situation is very similar in many industrialised countries with democracies,” he said. But, he warned: “The image or reputation of democracy is suffering, not only because of these US elections, but in general.”

In Switzerland, for example, the 2014 vote by a narrow majority to introduce quotas for migrants from the European Union put at risk not only a longstanding agreement with Brussels to guarantee the freedom of movement, but also jeopardised the many Swiss economic sectors that rely on foreign labour.

“The problem is that all these far right and populist parties raise all the problems, but they have no solutions,” said Linder.

After the 2014 vote, the Swiss president had to appeal for national unity and calm. Likewise, UK leaders scrambled to contain the damage after Britain’s shock decision this past June to leave the EU reflected the rise of working class anxiety amid an immigration surge.

Complications

According to a leading United Nations official, direct democracy can act as a counterweight to governments perceived as deaf to their own citizens.

“Direct democracy is undoubtedly one of the most efficient, reliable and transparent methods to determine the will of the people,” said Alfred de Zayas, an American international law professor in Geneva who is the UN’s top official for promoting democracy and equality in governments.

However, certain conditions must exist for these systems to succeed.

De Zayas said representative democracies – those based on representation through elected officials – have increasingly disappointed voters “because parliamentarians, once elected, rarely consult with their constituencies and sometimes take decisions that are clearly contrary to the expressed wishes of the electorate”.

The reverse also can lead to problems, as has been seen with the Swiss government and parliamentarians tying themselves in legal knots trying to figure how to implement the anti-immigration initiative.

Swiss example

However, the frequency of Swiss referendums provides something of a “safety valve” to guard against pressuring building up too much from any faction or movement, said Swiss political scientist Jürg Steiner, a political science professor at the University of North Carolina.

“Switzerland has some benefits, that the pressure is off to rebel against the establishment,” Steiner said. “In Switzerland, four times a year they can just decide on substantive matters, so if things go wrong they cannot blame the establishment.”

Perhaps most important, he said, is that people are no longer listening to each other, in part due to social media that makes it easier for people to live in their own worlds, so-called echo chambers. The big task for democracy is to overcome these divisions.

“We need more deliberation, which means that people are willing to listen with respect to arguments across deep divisions,” Steiner said.

“The lack of such deliberation can be seen in many places, for example in the EU about refugees, and yes, also in Switzerland. For me the main issue in the world is how to overcome these damaging divisions. We need less Trumpism, not only in the US but at many other places.”

How did they get it so wrong?

On the eve of the US presidential election, most national surveys gave Hillary Clinton a lead of around 4%, which translated into a high probability of victory.

The US pollsters who failed to accurately capture what was happening could learn a thing or two from the Swiss, said Steiner.

Swiss pollsters, he said, have learned how to adjust the results of a survey – helping improve their accuracy – when, for example, there is “a referendum on foreigners or a free labour market, and people are not exactly reporting what they are going to do. They may be embarrassed or ashamed”.

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.