Exploring the soul of Swiss architecture

Despite its small size, Switzerland has a trove of fine architecture. Not everything is built for beauty, but the best Swiss architects excel at transforming “age-old materials” into lasting or ephemeral treasures, as a new book shows.

The book, “Swiss Sensibility: The Culture of Architecture in Switzerland”, is a 256-page homageExternal link in lyrical essays and high-quality photos and drawings to the creative confidence and restrained artistry of Swiss architects, who enjoy a sophisticated culture of building design. Their small creative practices are backed by a strong education system, high quality craftsmanship and open competitions that encourage young talent.

From among hundreds of possibilities, author Anna Roos focuses on 25 diverse buildings in Switzerland designed by 15 influential Swiss architectural practices. They range from the jutting, austere grandeur of the San Gottardo Guesthouse on Gotthard Pass, to a delicately poetic 11-metre-high viewing tower at Reuss Delta by Lake Lucerne, and to the crisp elegance of a temporary base camp of aluminum and wood shelters set up on the Matterhorn in 2014 while the historic Hörnli hut was being renovated.

“It is the perfectly meted understatement one often sees in Swiss architecture that gives it its force,” Roos writes, while admiring the Gotthard’s Alpine guesthouse that mimics its craggy setting.

History of prominence

The Swiss have excelled at architecture for centuries. The Italian-speaking Swiss architect Francesco Borromini and his contemporaries, Gian Lorenzo Bernini and Pietro da Cortona, were leading figures during the Italian Renaissance. Borromini began by learning from his father, a stonemason.

More

Architecture

Charles Edouard Jeanneret, better known as Le Corbusier, is the most famous of 20th century Swiss architects. He began by learning from his father, who painted watch dials. Bruno Giacometti, Jacques Herzog, Pierre de Meuron, Mario Botta and Peter ZumthorExternal link also helped put modern Swiss architecture on the world map.

Central to the book is Roos’ interview with Zumthor at his home in Haldenstein, in the eastern canton of Graubünden. He describes how, after a building boom in the 1960s and 1970s, it was necessary to “rebuild the reputation of the architect” by showing responsibility toward the environment and respect for the past.

More

Inside Peter Zumthor’s 900-page, 6kg monograph

The venerated Swiss architect gained a huge international reputation from his work mainly by taking on small, complex projects. His previous awards include the 2009 Pritzker Prize – the world’s most prestigious architecture award – and Britain’s 2013 Royal Gold Medal. His newest award is the 2017 Association of German Architects (BDAExternal link) Grand Prize, an honour for lifetime achievement bestowed on July 1.

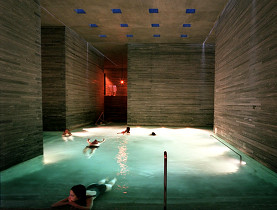

Zumthor is known for his careful use of materials in buildings that respond to location and function, and for the atmospheric quality of the spaces within. He began his career as a carpenter after learning from his father, a cabinet maker. Speaking with Roos, Zumthor compared his work process to being a conductor and composer with a big orchestra.

“I want to do something which works well and which fits to the place; as if it were for myself. I have to be excited about it. The building has to fit to the place; it has to fit to its use,” Zumthor says. “I write a building like a piece of music, like you would write a book, or write a poem and then this is just how it has to be.”

Levels of detail

In recent years, young Swiss architects have preferred modest designs and compressed wood, concrete and sheet metal rather than stone – a bow to economic, environmental and energy-saving concerns. While working on her book, Roos said she encountered architecture critics who use the term “Swiss” as a synonym for “good design”.

“If you ask me what characterises Swiss architecture, one of the things I would think first is the level of detail in the construction,” says Marilyne Andersen, a professor of sustainable construction technologies and dean of the School of Architecture, Civil and Environmental EngineeringExternal link at the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology in Lausanne (EPFL).

“Concrete is a material that is very often used in Switzerland, but with a level of professionalism that is very impressive,” Andersen cites as an example.

To her, Switzerland’s architecture is defined by its “sober and clean” features with a connection to where in the country it is built, whether in the mountains, on a lakeshore or on the plain.

Sense of materials

Not every building in Switzerland is designed well from an aesthetic standpoint, but even the most banal are usually well constructed. The iconic Swiss chalet popularised in the 19th century comes in all flavours ranging from kitsch to 21st century sleek. Most are built from available building materials that can withstand the Alpine climate.

The best Swiss architects bridge the modern with the old, the natural with the urban, and the luxurious with the economical. They rely on a deep-rooted tradition of craftsmanship that pervades stonemasonry, carpentry and other related fields, the book observes, and there is little class division between the architect and the craftsperson.

Other important factors include practicing architects who work in academia, clients that respect good work and have the means to pay for it, and Swiss architects’ intimate knowledge of their working materials.

“It is this deep understanding of the physical nature of making objects out of age-old materials – wood, stone, glass, concrete – that shines through the buildings of many Swiss architects, both historically and today,” Roos writes.

In the book, Swiss-American author R. James Breiding contributes an essay highlighting the precision, frugality, reliability and trustworthiness that he views as chief characteristics of Swiss architecture. “Collectively,” he writes of Switzerland’s 26 cantons and 2,249 communities, “it is a laboratory for architectural experiment and individually a dream for any budding architect.”

Landscape-driven

Motivated by her curiosity about the Swiss approach to design, Roos provides the insider and outsider perspectives needed to explain the Swiss minds behind these spectacular buildings – and the mélange of influences that produce what she describes as a “rich and deep-rooted tradition of architecture in Switzerland”.

In an interview, Roos, an architect, teacher and writerExternal link, emphasises that Swiss architects tend to exhibit an intimate relationship to the landscape even in urban environments.

“It’s this ability to show the innate qualities of material, for the innate quality itself,” she says, “and to put these together in a way that keeps the weather out, that looks clean and concise and is beautifully built”.

More

The Swiss in charge of architecture and design at MoMA

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.