Are Swiss banks really chopping environmental devastation from trade financing?

As awareness of the Amazon rainforest’s role in balancing the global climate builds, banks financing Switzerland’s important commodity trading sector are starting to re-evaluate the environmental impact of their business.

In February, BNP Paribas, once the world’s leading trade finance provider, announced it would no longer financeExternal link companies that produce or trade beef and soybeans originating from land cleared in the Amazon after 2008.

BNP Paribas’ move came just weeks after it joinedExternal link Credit Suisse and Dutch lender ING – whose trade finance desk is also in Geneva – to stop loaning to traders that buy and sell oil from the rainforest in Ecuador.

Trade finance allows for commodity traders to buy and sell large volumes of raw materials by having banks take delivery of shipments, and enable them to manage their own risks. Banks become consignees of customs documents and cargos. With much of global commodity trading being conducted in Geneva, most financial institutions offering credit to the traders have also made the Swiss city a main hub for their business. This differs from project financing where banks lend money to companies to prospect for oil or grow crops.

According to the latest study by the Swiss Trading and Shipping Association (STSA), Switzerland is the biggest global hub for trade finance, followed by the United Kingdom.

Commodity trading represents 4.8% of Swiss GDP, employing roughly 35,000 people in the country, according to the latest data from 2018 provided by the Swiss Trading and Shipping Association (STSA), an industry group which also includes trade finance banks among its members.

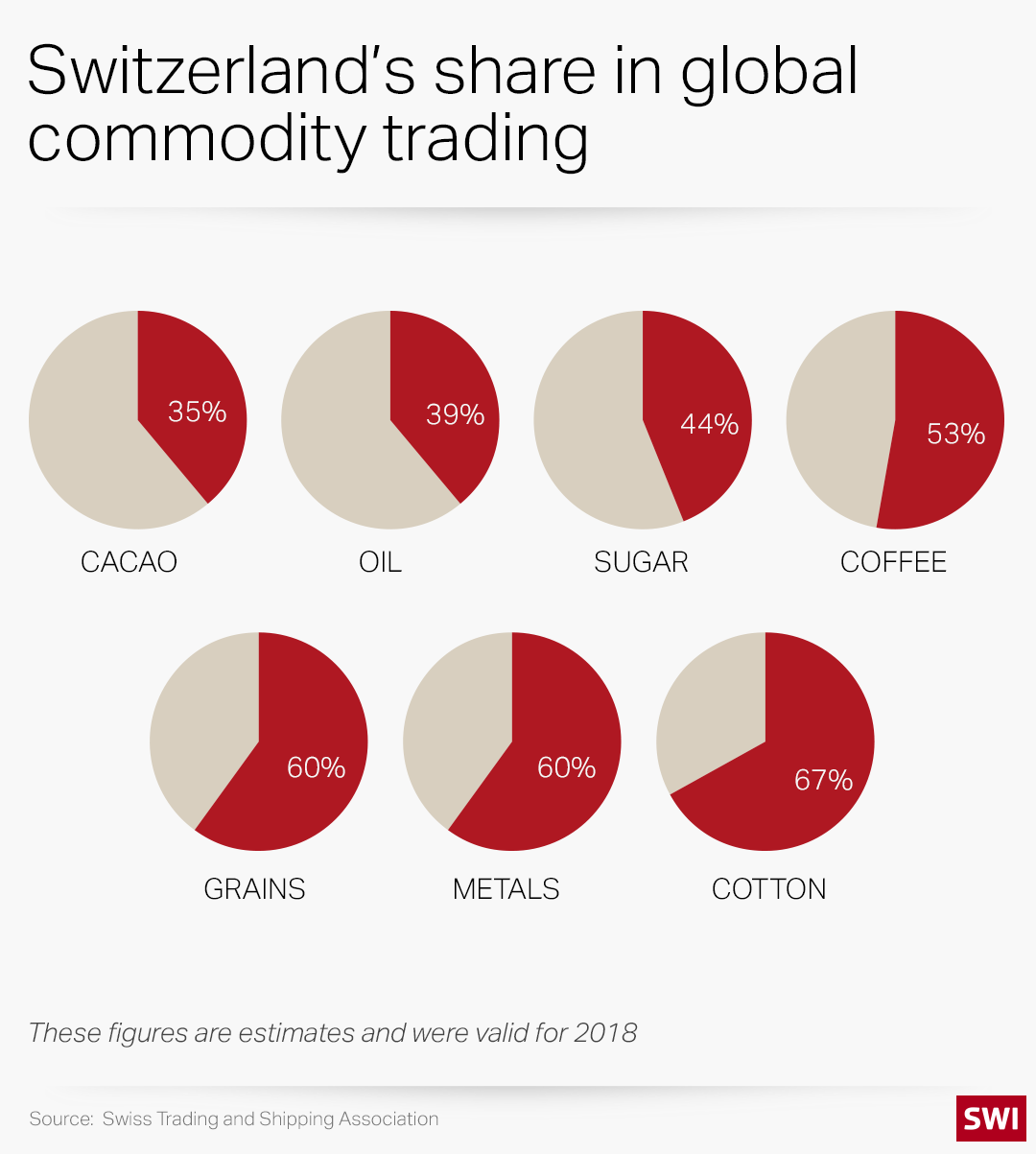

Swiss traders buy and sell 39% of the global oil, 44% of sugar, 60% of metals and 53% of coffee. STSA was unable to provide corresponding estimates for the global trade of soya and beef.

‘Polluted’ money

Trade financing is part of a billion-dollar commodity trading industry which is responsible for oil spills within the Amazon Sacred Headwaters region of the rainforest, home to half a million indigenous people. Contaminated rivers have left local communities at times without drinking water.

In April last year, for instance, a pipeline burst and spilled crudeExternal link into the Coca River, in an area that had already experienced years of toxic waste dumping by the Chevron-Texaco Oil Company.

“The impact of the financing is very serious. Our lands have been polluted: they are covered in oil and full of injustice. There is no drinking water, no education and there is no health,” Marlon Vargas, president of the Confederation of Indigenous Nationalities of the Ecuadorean Amazon (CONFENIAE) told SWI swissinfo.ch by phone. He said oil extraction along the Amazon River’s tributaries “exploited” the Indigenous communities’ territories.

A 2020 report by campaign group Stand.earthExternal link and Amazon Watch named six mostly Geneva-based trade finance banks for financing some $10 billion worth of oil since 2009, from Ecuador’s Amazon to the United States. The fossil fuel is sourced in one of the most biodiverse rainforests on Earth – with future expansion expected in the Yasuni National Park, a UNESCO World Heritage site. The report prompted several banks to make public announcements. By January, in addition to ING, BNP Paribas and Credit Suisse, Dutch bank Rabobank announced that it had stopped financing the cargos in early 2020.

Contacted by SWI swissinfo.ch, Credit Suisse confirmed it would phase out supporting trades of Ecuadorean and Peruvian oil. In a statement, the bank wrote that it “reviews and updates its sector-specific policies on a regular basis” and “introduced further restrictions on financing fossil fuels in the course of last year.”

Turning point for corporate responsibility?

The question of cleaning up business in environment sensitive zones is not new. For many years, retailers and producers relying on commodities sourced in the Amazon and other vulnerable environments, as well as traders themselves, have announced both in-house and industry sustainability standards. Many of these were non-binding and their implementation lacked independent oversight.

However, increasingly pressure is building on the commodities sector to change behaviours. “For commodities producing companies and for commodities trading companies, they see that responsibility of environmental degradation and human rights violations is extending beyond the direct affiliate and subsidiaries on the ground and goes more to the parent company and those involved in the commercialization of commodities,” said Gilles Carbonnier, professor of development economics at the Graduate Institute in Geneva. He said he is seeing a shift in the sector that may be driving it to divest or distance itself from risky business.

The expert said civil suitsExternal link brought by affected communities suing – and winning – against polluters in foreign courts where commodities companies are based have raised the stakes of businesses’ involvement in environmental and social abuses within their supply chains. In 2020, six years after BNP Paribas was found guilty of violating US sanctions by financing Sudanese oil trading, Sudanese victims reopened the case in France, accusing the bank of complicity in crimes against humanity.

“Social expectations and norms are also shifting rapidly towards climate change, which have become major concerns not only of governments but civil society organisations,” Carbonnier added. “The Amazon basin and the preservation of the rainforest is becoming quite an issue, especially the Ecuadorean Amazon.”

The change observed in corporations is also in line with how Switzerland wants to portray itself. Two years after the formal end of Swiss banking secrecy, the country has been seeking to promoteExternal link itself as a global centre for sustainable financial services. Many of the largest trade finance banks are part of Sustainable Finance GenevaExternal link (SFG), which has mobilised cooperation between the city’s banking sector and International Geneva, including international organisations, NGOs and think tanks.

Jean Laville, deputy CEO of Swiss Sustainable Finance, a nationwide industry group that SFG is part of, said trade finance banks are facing a “new paradigm”. He said that there is now a realisation that the sector is “on the bad side of history.”

More

Deforestation: Are banks still taking a big cut?

Can do better

Andreas Missbach, head of commodities, trade and finance at civil society group Public Eye takes a starker view of the banks. Public Eye recently penned a report entitled “Trade Finance Demystified”External link, which underlines the lack of transparency in the attribution of credit by Swiss banks to the traders, and that banks themselves have little appreciation of the details of the multitude of trades that they finance.

“Banks have no clue at all of what is being done (with the financing) and where the traders source from,” said Missbach. He also doubted that trade finance banks may have been motivated by environmental concerns to discontinue financing for oil trades, as was the case in Ecuador.

According to a follow-up statementExternal link by Stand.earth, some banks are still flying under the radar. In January, the NGO pointed its finger at Natixis, a French bank working with Swiss traders, saying it was “the only bank among the top six to make any trades in Amazon oil after the release of the [August] report.”

Stand.earth researcher Angeline Robertson said that Natixis continues to finance oil trades from the Amazon region.

Another bank surveyed by Stand.earth is UBS. Robertson said in an email that her organisation and Amazon Watch, have shown that “UBS did not apply their standard correctly to its trade financing for Amazon oil until we publicised information about that breach. This gives us concern that without active stakeholders taking the lead, UBS may overlook other potential breaches of their policy.”

“We believe that without a proactive commitment to ending financial support for Amazon oil, UBS cannot currently assure Stand.earth and Amazon Watch, nor the banks’ investors, that the bank can avoid negative impacts in the Amazon from its banking activities,” the research teams concluded.

Responding to questions, UBS sent a statement to SWI swissinfo.ch in which did not specify any changes in business by the bank toward financing Amazon oil. It did however say that a “constant dialogue with numerous stakeholders and non-government organisations” is being maintained, and that it applies an “in-depth environmental and social risk policy framework to all of our transactions, products, services and activities, including Commodity Trade Finance.”

While the Ecuadorean oil report may have moved banks to consider their reputational risk over continued support of “dirty” trades, on the demand side for trade finance, some energy traders are also undergoing profound shifts in business. Informally, traders admit that climate regulation and the surge of e-mobility is kickstarting a rethink in investments.

For the people on the ground more could still be done by the financial institutions.

“That three or four banks have suspended finance to Ecuadorean oil is a great achievement. for humanity. We hope that more banks, that they all, will stop financing,” said Vargas, the indigenous leader. “What they are doing is totally contradictory to what they say at international climate conferences. Some banks are simply not respecting the rights of indigenous people. They are causing so much damage to the existence of humanity.”

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

Join the conversation!