Treehouses of language: inside a Swiss literature foundation

Rousseau, Hesse, Highsmith, Mann – fabled, yes, but did any of them ever write a book in a treehouse? A new centre for literature is offering global writers the opportunity to do just this.

Arriving in the small Swiss town of Montricher, surrounded by farmland and rows of vines, you might wonder about the large construction looming over the eastern edge of the village. Is it a futuristic research centre? The all-white complex, with several cabin-like pods suspended underneath a vast overhanging canopy of elliptical shapes, looks like the space-age dream of a Silicon Valley billionaire.

It is not – at least not quite. It is the Jan Michalski Foundation for writing and literature: a philanthropic venture run by Vera Michalski-Hoffmann, a Swiss publisher and patron who named the centre after her late Polish husband. Go further in amongst the pillars of the ultramodern architecture and you will find a five-floor, eight-language library; an exhibition space (currently dedicated to Federico Garcia Lorca); and – since the beginning of this year – a collection of writers from around the world, chosen to come and stay on a revolving basis.

More

Irish author maps out literary Switzerland

So far, says Aurélie Baudrier, head of communications at the centre, the results are positive. After years of development, designing, gradual openings to the public, getting the writers on board was the final “piece of the puzzle,” to borrow a phrase from her boss, Michalski-Hoffmann. And the quality of the applications, as well their volume, has been phenomenal: 900 were received for this year’s residencies, of which just 29 made the cut.

Is it the sign of a literary boom in Switzerland? After all, just several kilometres down the road from Montricher, the equally-impressive Château de LavignyExternal link welcomes global writers for similar residencies; the shores of Lake Geneva, a few minutes further again, are host to several international literature festivals throughout the year – the Salon du LivreExternal link, the far°External link festival in Nyon, Le livre sur les quaisExternal link in Morges – and this is only French-speaking Switzerland.

‘Fire up your brain’

Either way, with a history ranging from Rousseau to Hesse, as well as current interest in Swiss literature (spurred by global successes such as that of Genevan Joël Dicker) it’s small wonder so many foreign authors are keen to come. The conditions in Montricher aren’t bad either: return travel from home country to Montricher, breakfast and one meal per day, accommodation in a hanging pod (more on this later), and a CHF1,200 monthly allowance.

I go to meet some of them. The first, Taran Khan, is a journalist and essayist from Mumbai. She is half-way through a three-month stay at the foundation, writing a book about the cultural life of Kabul. Why does an Indian author come to Switzerland to write a book about Afghanistan? The beautiful location, the calm, the 60,000-volume library, all offer “a break from the daily structures of her life” in Mumbai, she says. She can step back, take time, and “see the connections in her own work that [she] would not otherwise have seen.”

There are also the other ‘writers-in-residence’. At any one time, around half-a-dozen international authors are staying in the centre – swapping ideas, cooking together, walking together in the grounds. And the fact that they come from such diverse parts of the world (this year writers have come from Poland, Brazil, America, Singapore, Iceland, Egypt, Wales, and more) can make for serendipitous interactions. It can help “fire up your brain,” Khan says, and avoid getting bogged down in a project.

‘Pardon America’

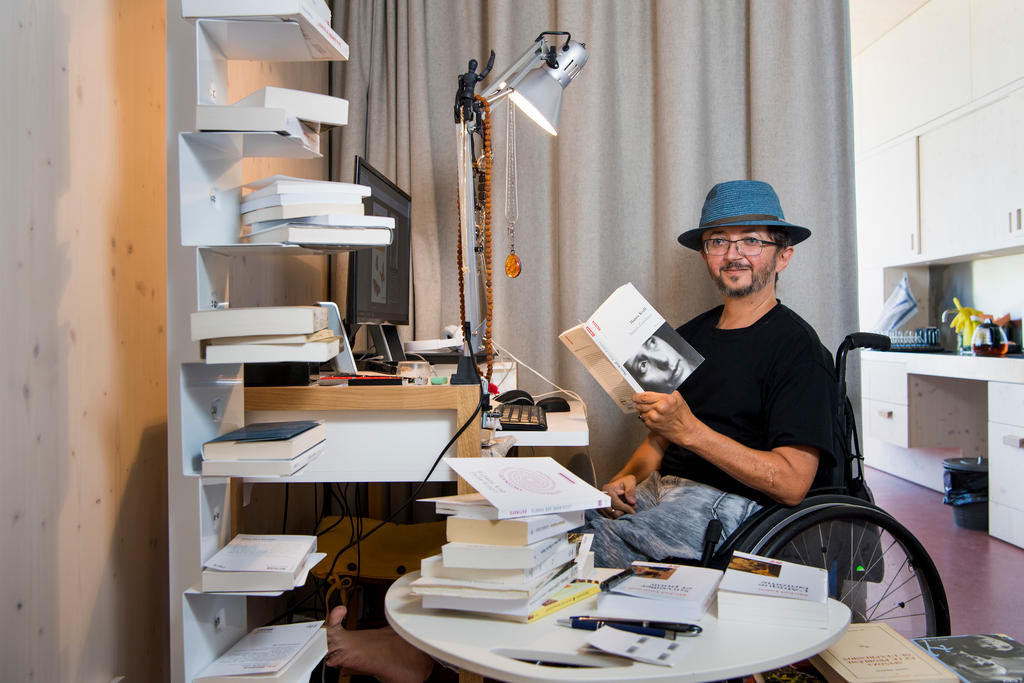

I meet one of these others, Philippe Rahmy, in his “treehouse.” It turns out that the hanging pods – they are not hanging, of course, but artily erected on staggered levels – are called treehouses, and they are where the writers live and work. Since my request to spend a night in one had been politely rejected (no vacancies), Rahmy hosts me with a coffee in his, a large box-like container with a vast view over the plateau towards Lake Geneva. This one is big and specifically tailored to disabled writers (Rahmy uses a wheelchair).

He has little interest in talking about the facilities. Barely have we sat down that he is pouring forth about his current project, his previous projects, his views on writing, his recent trip to disadvantaged areas of Florida, his background of German and Egyptian parentage growing up in Switzerland, his struggles to overcome a debilitating bone disease. A prejudice of mine, before coming to the Foundation, was that it might be staid and boring; Rahmy blows this away in a short minute.

Here, he is working on an account of his travels through the US, where he spent time with wrongly-convicted prisoners and undocumented children working in fruit plantations – kids who, he says, were literally chained to their beds at night by their “owners” so that they wouldn’t try to escape. Rahmy wants to collect their stories in a book, called “Pardon America”, that will be neither fiction, nor non-fiction, nor journalism, but something combining features of all three.

Above all, he explains, writing is an exercise in empathy, beyond questions of style and structure, which he feels have stifled literature for decades, especially in the French-speaking world. Rather, he says as he gifts me a copy of his latest work, Monarques, writing is about “bringing your own subjective umbilical cord into how you see the world,” in order to “challenge it on a common ground of empathy.”

‘We all need words’

This sounds great in theory, but in practice? Such a foundation, just like some perceptions of literature in general in an economics-obsessed age, could easily be seen as an out-of-touch ivory tower perched comfortably on its hillside while a carefree world spins slowly below.

More

Time travelling writer returns to Switzerland

The third group of writers I meet, the “mobile characters collective” from Lausanne, not far from Montricher, are trying to bridge the divide. Rather than spending the days in their secluded treehouse, they have set up office on a table outside the main shopping centre in the village; every morning, for several hours, they take “orders” from local residents to prepare short texts – poetry, prose, experimental – on specific topics.

Writers for hire? No, says Mathias Howald, one of the members. It is a new way of approaching the writing process: inspiration is no longer that of an isolated individual but rather born of fresh interactions with members of the public. “We are bit like scribes,” says Benjamin Pécoud, referring to the role of ‘écrivain public’ that is still common in the French-speaking world. “But we are more like ‘auteurs publiques’ [public authors] than écrivains publiques”.

They show me an example. A one-page arrangement of poetry, the words spiralling and forking into the shape of a tree, which the third member of the group, Catherine Favre, prepared for a local man who wanted something to represent his work in forestry. Others have asked for even more personal texts; requiems for dead family, divorce, living with Down’s Syndrome.

So far, the feedback is overwhelming. They received over 100 requests and the mayor of the town asked the group to prepare the text of his speech for the annual Swiss National Day on August 1. After the period in Montricher, the group plans to collect all the works in a collection, a small genealogy of the town, before moving on to repeat the experiment somewhere else, perhaps in German-speaking Switzerland.

It is a project with legs, they believe, and a worthwhile one. Because, ultimately, “we all still need words.”

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.