Banks face expensive US tax ‘holding pattern’

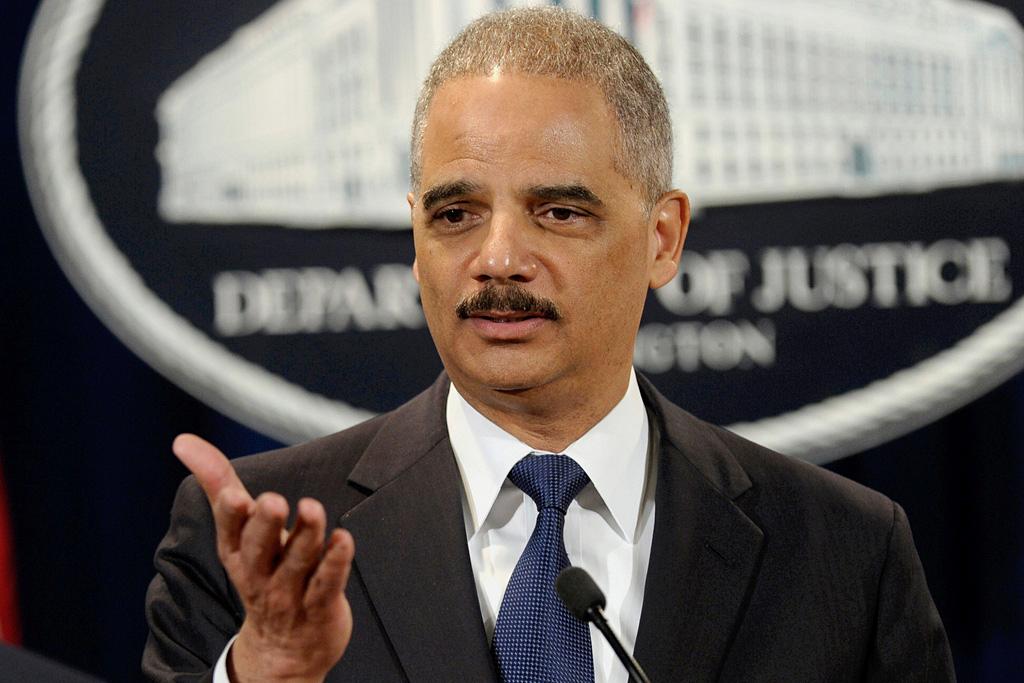

Around 100 Swiss banks are bleeding money as they wait for a legal process, aimed at resolving United States tax evasion issues, to regain momentum. The programme ground to a halt last autumn after a row over small print with the Department of Justice (DoJ).

Banks had hoped that a deal negotiated by the Swiss government and the DoJ in August 2013 (see box below), would clear up legacy tax evasion issues by the end of last year. But many Swiss banks have entered 2015 still uncertain of whether this will be put to bed in the next 12 months.

“The message being sent out by the DoJ in 2013 was that they wanted this issue to be closed by mid-2014,” Fabio Oetterli, a lawyer appointed by the Swiss Bankers Association to help banks through the legal process, told swissinfo.ch. “We hope the programme will be closed by the end of this year, but it is the DoJ that controls the pace.”

“All the while that banks are waiting, the costs continue to mount because their lawyers are still active,” he added. “Banks used to assume that the DoJ penalty would absorb two-thirds of their total costs with another third taken up by legal expenses. Now they have reversed that ratio.”

The process hit a major snag last October when Switzerland rejected the DoJ’s Non-Prosecution Agreement (NPA), a document intended to be used to wrap up individual cases against banks. The most contentious article in the NPA was a demand that the US could share banking information with other countries – a clause that clearly violated what is left of Swiss banking secrecy laws.

It has now been sent back to the drawing board. Negotiations are ongoing but no timeline has been set for its redrafting, or even any guarantee that the US will back down on the contentious points.

Serious dollar signs

A sense of how much this is costing banks was delivered by regional banking group Clientis late last year. Clientis, comprising 15 small domestically-focused bank with no history in the US, racked up CHF500,000 ($490,000) simply determining there was no case to answer. The group then promptly withdrew from the US tax programme in December.

Those banks still in the programme, having worked overtime to churn out a mass of data supporting their presumed culpability in the US, now find themselves in an uncomfortable “holding pattern”, according to Milan Patel, a lawyer at the Anaford practice.

“I would not hold my breath for a revised NPA before the summer or for any final resolutions with banks before the late autumn at the earliest – and perhaps even later,” Patel told swissinfo.ch. “There are law firms out there that are seeing serious dollar signs.”

“The DoJ is woefully behind in this process. More banks entered the programme than they anticipated and they simply don’t have enough people to deal with it.”

According to the DoJ, 106 banks signed up under the most onerous category 2 (see box below) at the end of 2013, signalling that they had broken US laws by allowing tax cheats to hide money in their vaults. But after carrying out due diligence, around ten pulled out last year believing that they were not guilty of criminal acts after all.

Patel does not rule out more banks exiting the programme this year. “It boils down to two basic questions: cost, or calculating the penalty that needs to be paid to fix the problem,” he said. “The second question is culpability – did we really do anything wrong?”

Pope proving virginity

In many cases, the process of negotiating a penalty is not likely to prove straightforward as the banks and the DoJ might have different ideas of exactly which accounts broke US law and the extent to which banks were responsible for enforcing US tax compliance on clients at the time.

In addition, some clients are playing hard to get with banks when asked to provide proof that they have joined a voluntary disclosure tax scheme in the US – which would give banks some mitigating evidence to soften penalties. It appears that such clients are unwilling to help the bank save costs when they are facing a severe tax bill themselves.

It is not known exactly how many banks joined the programme in the latter half of 2014 in categories 3 or 4, but this number is believed to fall far below the category 2 entrants. The Raiffeisen group is the biggest name to confirm category 3 status, but many decided there was no point as categories 3 and 4 simply state that the banks believe that they are innocent.

Or as Patel puts it: “It’s a bit like someone asking the pope to prove that they are a virgin.”

Patel believes that the DoJ will leave category 3 and 4 banks until they have dealt with the category 2 batch. Some of the dozen or so banks in the so-called category 1 – not able to join the non-prosecution programme because they were already under active criminal investigation – may also have to wait the best of a year to learn their fate as the DoJ may want to use information gathered from category 2 banks against them, Patel speculated.

Uncertainty remains

Another Swiss lawyer involved in the process, Carlo Lombardini, believes that the whole programme was badly thought out and negotiated from the Swiss side. Whilst under the severe pressure of watching banks, like Wegelin, disintegrate under the weight of DoJ charges, the Swiss authorities should have done better, Lombardini told the Swiss News Agency (ATS).

“There is much uncertainty. The programme was negotiated poorly,” he complained in the recent interview. Lombardini lamented the fact that banks are struggling to get to grips with the text of the agreement that is often vague and appears loaded against them.

“The Americans intelligently applied the leverage that had been able to gain” from successfully prosecuting UBS and smaller banks like Wegelin to force Switzerland into an unequal bargain, he concluded.

The Swiss Bankers Association declined to comment. The State Secretariat for International Financial Matters (SIF) said that it had intervened to object to the original NPA.

But the authorities, having set up the framework of the agreement, are no longer actively involved in the legal process. It is now up to individual banks to negotiate their cases with the DoJ.

The non-prosecution agreement signed between Switzerland and the US in August 2013 sets out a programme for Swiss banks to avoid landing in the US courts on tax evasion offences. Those banks that believe, or suspect, that they may have illegally accepted the assets of US tax cheats had to register by the end of 2013. Some 106 banks chose this route, although some may have had their arms twisted by the country’s financial regulator. These banks had to supply the DoJ with documentation last year showing their business activities in the US, including names of lawyers and other parties they dealt with and the names of their own staff involved in such business. They did not, however, have to provide the names or account details of their clients. Penalties will range from 20% of the value of assets held in accounts opened before August 1, 2008 to 50% in accounts opened after February 28, 2009.

Banks that have US clients but believe they complied fully with US tax law were able to enter the programme as category 3 between the end of July and December 31 last year. The same entry window was open for category 4 banks that are so small they have no US exposure.

The DoJ did not allow 14 Swiss banks, or Swiss-based branches of foreign institutions, to join the programme because they were already under active criminal investigation in August 2013. These included Credit Suisse, which was fined $2.8 billion last year, Julius Bär, Pictet and the cantonal banks of Zurich and Basel.

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.