Bombed-out Swiss village used as training ground for disaster operations

Switzerland is home to a unique derelict, bombed-out village near Geneva where rescue teams from around the world come to train for missions in earthquake or war zones.

A narrow street and winding paths lead through the village of Epeisses on the banks of the Rhone river in canton Geneva, near the border with France. The word “village” is misleading – this former gravel pit contains a dozen concrete ruins, burned-out cars and a few containers. All that remains of the local Hotel Ibis are chunks of stone and a crooked sign. If the bombed-out houses were any taller, one would think this was Aleppo in Syria.

A dog clambers over the concrete blocks and debris, sniffing around in cracks and crevices, before stopping and starting to bark. It has detected human scent.

The man who is pulled unscathed from the rubble after hours of waiting on this gloomy November day is a member of the Swiss military rescue force. As part of a refresher course, he was assigned the role of earthquake victim.

The man spent the night in a sleeping bag under tonnes of rubble. With no internet connection, he whiled away the time by scrolling through the photo library on his smartphone. “I sorted through a thousand photos,” he says with a grin. Now he is tucking into a plate of steaming potatoes with meat and gravy.

Not an extra burden

Several metres away, people in orange protective suits are ladling out dry food mixed with hot water. They are rescue troops from different countries, who have come here to receive UN certification for international missions. The fact that they can only eat packet emergency food is part of the so-called classification process.

When international rescue teams are sent abroad after earthquakes, floods, forest fires or explosions, they are supposed to help the authorities there and not be an added burden, for instance because hotel rooms and meals have to be organised. As a result, the teams here must also be self-sufficient for ten days.

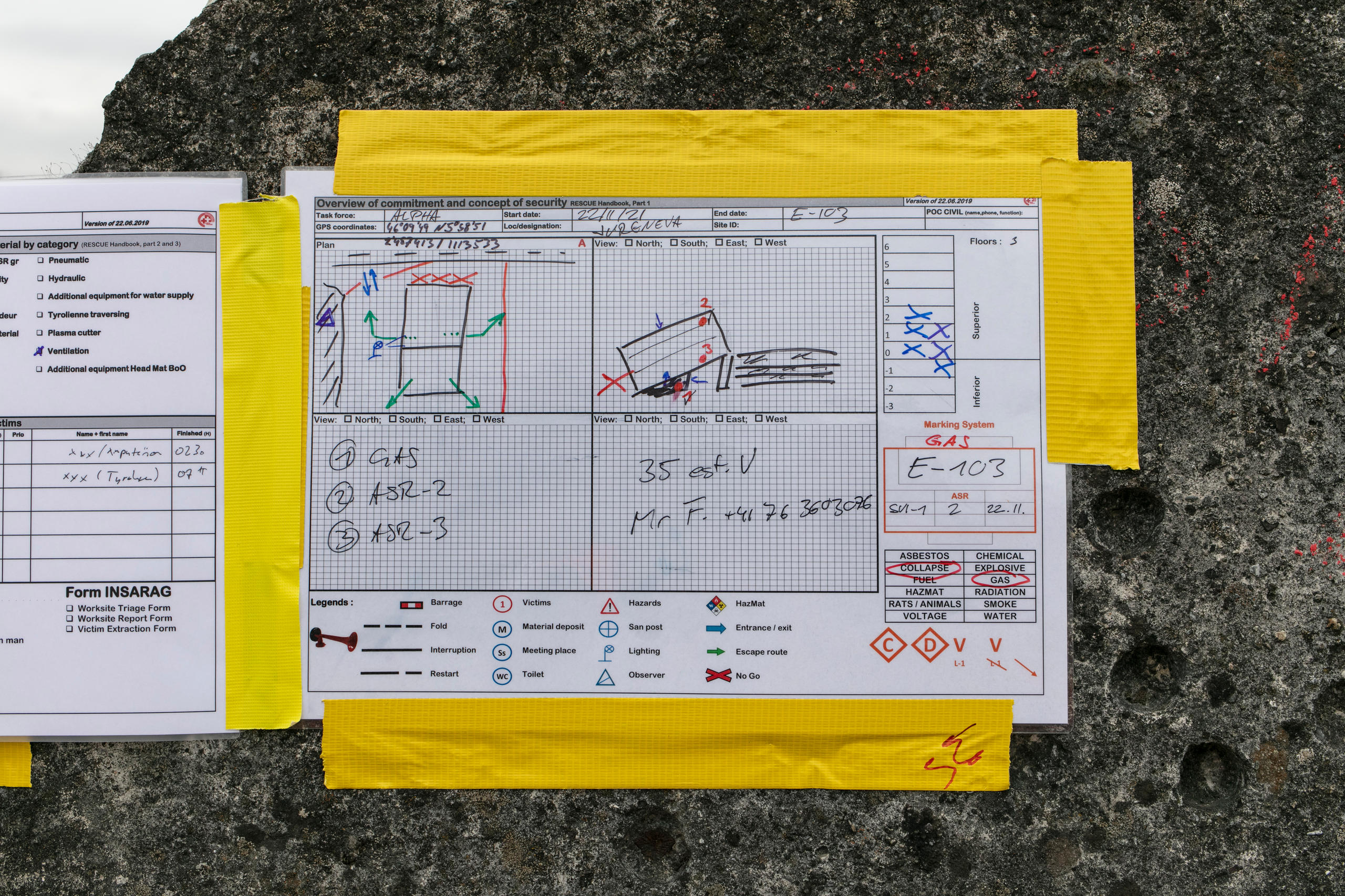

The training scenario is also very specific: a magnitude 7.1 earthquake has struck the Geneva area. Thousands of people have been buried. Rescue workers from France, Germany and Switzerland now have to retrieve the victims from the rubble.

The exercise lasts 48 hours and is organised by the Humanitarian Aid Unit of the Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation (SDC) and the Swiss armed forces. Pompiers de l’urgence international, @fire Germany and Swiss Rescue are being evaluated for their UN classification. Teams from Armenia, Holland and Luxembourg are taking part for training purposes, but will not be assessed. Everything must take place as in a real emergency. Only the buried “victims” are exempt from this. If they start to feel unwell, they may use an emergency tunnel.

Practising for the real thing

Tents have been set up a few hundred metres from the training village. We have to be quiet.

“Team Alpha is sleeping at the moment,” explains Martina Durrer, team leader at Swiss Rescue. “Team Alpha and Team Bravo work in eight to twelve-hour shifts.” The participants eat and sleep in the tent village. Before entering, they must first wash and disinfect themselves. This is not just because of Covid, but also because of any asbestos residues, which could be present in real earthquake or bomb debris.

Everything is managed realistically down to the last detail. For instance, there is no fresh milk for coffee, only powdered or condensed milk – you cannot take refrigerators with you on mission. Even the contents of the dry toilets, which the teams have brought along, will be taken away at the end of the operation, as no traces should be left behind.

What cannot be simulated, however, are the dust, the smell of corpses and screaming relatives begging you in a foreign language to dig for their buried family members.

“What cannot be practised is the stress of a real emergency, the encounter with suffering and death,” says Manuel Bessler, head of Swiss Humanitarian Aid. But the technical side can be rehearsed very well, he adds.

Realistic rubble village

Epeisses is so realistically modelled on real earthquake or bomb destruction that rescue teams from around the world come to Switzerland to train.

“This training village contains particularly ‘realistic’ rubble sites,” says Lieutenant Colonel Frédéric Wagnon of the Swiss armed forces. Switzerland recreated the destroyed houses and debris encountered by Swiss Rescue in real missions abroad between 2000 and 2008, by building and then blasting them with explosives. This is the only such place where teams can encounter a situation as unstable as in reality.

Other countries, such as Germany or Morocco, would like to create their own rubble villages following the Swiss model. After each exercise, the site is restored to its initial state for the next session.

And there will be more training exercises. “We want to strengthen cooperation at a national and international level,” says Wagnon. The army and civil organisations such as the police and fire brigade are not the only ones to use the village for training purposes. There are also international organisations like the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) and the International Organization for Migration (IOM).

Training, not intervening

Near the heaps of rubble, where victims are being lifted out by rope or carried away, men in blue jackets are watching the action closely. They are UN experts conducting the classification, which must be renewed every five years.

“The UN wants to extend international standards, so that teams on the ground can cooperate better,” says Simon Tschurr of Swiss Humanitarian Aid. The classification of international teams is also useful for the local authorities, he says, who then know what they are getting. “It’s like a common international language, akin to what doctors and engineers use among themselves,” says Tschurr.

However, according to Tschurr, interest in receiving help from international teams has waned.

“As time goes on, more countries have their own rescue teams,” he explains. It also makes more sense for Switzerland to train foreign teams than to send its own to the four corners of the globe.

“In a disaster, time is of the essence,” says Tschurr. Local teams are on the spot much faster than international ones, he points out.

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

Join the conversation!