Can democracies resist rigged election theories?

Against all odds, both Brazilian presidential candidates accepted the outcome of the election in Brazil on Sunday. But improved digital literacy and robust electoral institutions may not be enough to stand up to the ‘big lie on stolen elections’ theory, analyses the SWI swissinfo.ch global democracy correspondent.

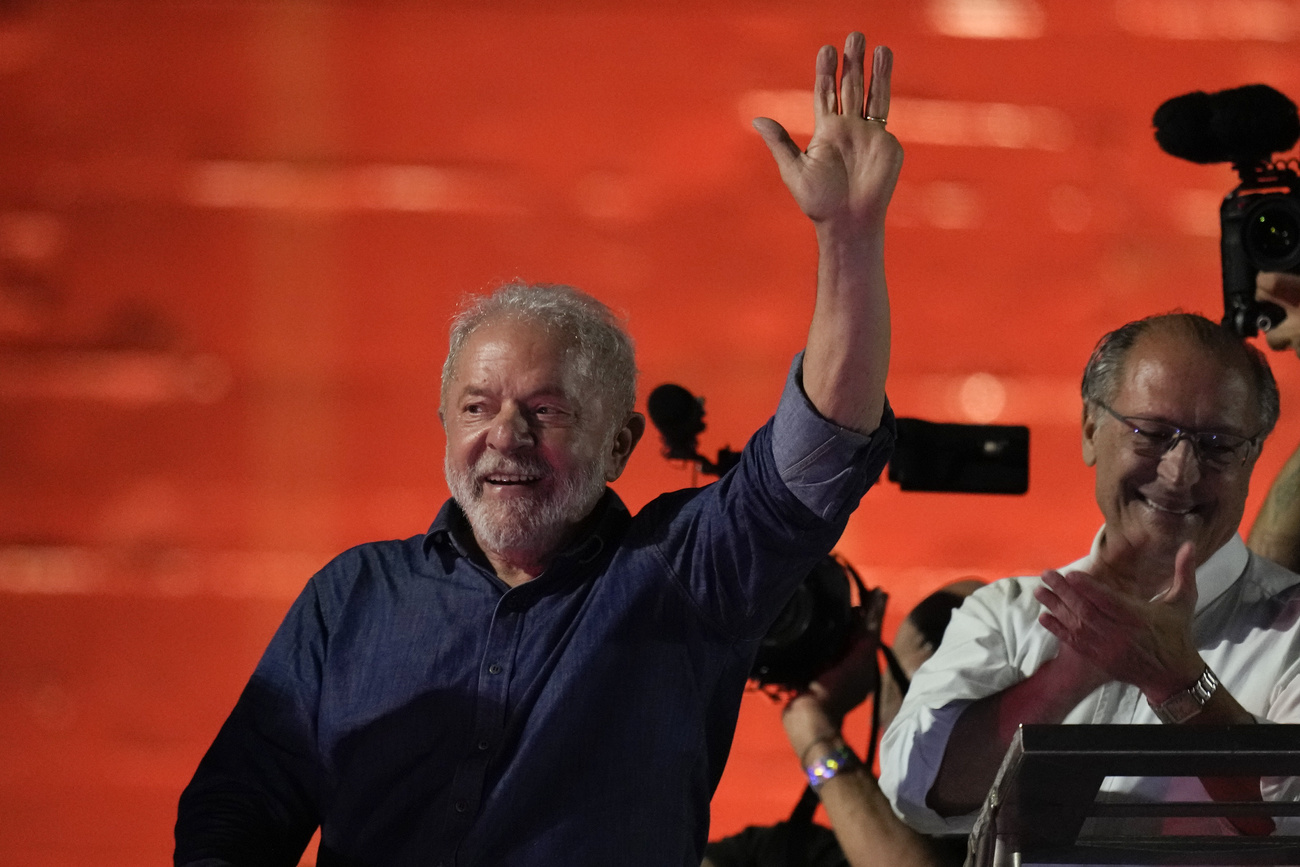

With all 120 million votes counted, Brazil’s Supreme Electoral Court (TSE), which runs the country’s elections, announced early on October 31 that Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva won 50.9% of votes, against 49.1% for the incumbent president, Jair Bolsonaro. Supreme Court Justice Alexandre de Moraes, who is also head of the TSE, called the election a big “victory for democracy, for the Brazil society and the voters”.

While Bolsonaro has yet to officially concede defeat and to congratulate the winner, he didn’t fall back on his “big lie on stolen elections” playbook which he had threatened to do in the run-up to the elections. Instead, Bolsonaro authorised his chief of staff, Ciro Nogueira, to start the transition of presidential powers. This was commented by the president-elect Lula on TwitterExternal link: “I am sure we will have an excellent transition, We will build a government for all Brazilians.”

More

Lula election ‘victory for Brazilian rainforest and indigenous people’

Can a peaceful transition and uncontested change of power in the Latin American country – the world’s fourth largest democracy – stabilise a world of crises, in which properly run popular votes, both elections of candidates and referendums, have increasingly been questioned from within?

‘Safeguarding Democracy Project’

One of the first examples of a contested election was the disputed United States presidential race between then Governor George W. Bush and Vice President Al Gore over twenty years ago. “Since then, a segment of conservatives and Republicans are talking about widespread voter fraud in spite of all reliable data pointing to the contrary,” Richard L Hasen told SWI swissinfo.ch.

Hasen is professor of law at the University of California in Los Angeles and leads the “Safeguarding Democracy Project”, which studies the “big lie on stolen elections”, a “hallmark of the [Donald]Trump presidency”, according to the scholar. This is designed to both “rile up the Republican base against Democrats and [set ]a basis to pass laws to make it harder for people to register and to vote”, he adds.

More

The US election shows democracy at its best – and worst

Interestingly, the 2020 US presidential election was called the “most secure in American historyExternal link” by the Cybersecurity & Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA), the competent authority that belongs to the United States Department of Homeland Security.

Despite his defeat, Trump nonetheless continued to claim that the election was “stolen from him”, leading up to the January 6, 2021 attack on the US Capitol building by his supporters. This resulted in the death of six people and injuries to over 130 police officials.

More

‘Disturbing, shocking, historic’: Swiss papers react to US Capitol riot

According to Hasen, the “big lie” is far from over. “In the upcoming mid-term elections, we see many Republican candidates running for electoral offices openly supporting the ‘big lie on stolen election’ narrative,” he said. This suggests that the freedom and fairness of electoral democracy is increasingly politicised and open to partisan bias. A recent CNN pollExternal link showed that around half of Americans (53% among Republicans and 49% among Democrats) believe it is at least somewhat likely that in the next few years officials will successfully overturn the results of a US election because their party did not win.

No US “Court of Democracy”

The decentralised structure of the US leads to institutional weaknesses. Unlike Brazil, for example, America has no comparable Supreme Electoral Court, a sort of “Court of Democracy”.

Hasen sees an additional weakness: the viral spread of disinformation on social media. “We need legal measures making it a crime to spread false information about when, where and how people vote,” he argues.

However, he does not support a strict regulation of social media, like in Germany, where the Network Enforcement Act covers the regulation of all social media platforms with more than two million users. The German law stipulates that such platforms must ensure that complaints are carefully examined and that all illegal content is removed within 24 hours. Instead, Hasen sees the broader need for “concerted collective action against any attempts to subvert election results”.

This proposal was backed not only by scholars in Brazil ahead of the election, but also in Switzerland.

“Hidden under the repeatedly voiced suspicion of election fraud are manifold efforts to restrict the right to vote in general,” says Sina Blassnig, assistant professor at the University of Zurich’s Department of Communication and Media Research. She describes the American and Brazilian systems, which have presidential regimes, as “much more susceptible to ‘stolen election’ campaigns” than the Swiss system, which has a proportional representation voting system.

Big small lies in Switzerland

In Switzerland, small “big lies” are most likely to occur in connection with controversial referendums, says Blassnig. “Before the [Covid-19] referendum vote last fall, such statements circulated sporadically on social media.” This was confirmed by Beat Furrer, press spokesperson at the Federal Chancellery, Switzerland’s highest electoral authority. “In the run-up to the votes on the Covid-19 law in 2021, there were attempts (primarily via social media) to cast doubt on the correct conduct of the votes,” he declared.

“The overall effect of these efforts remained limited. The voting complaints that were subsequently raised were dismissed by the relevant authorities, if they were acted upon at all”, Furrer told SWI by email last week. He added that voting complaints are also repeatedly filed to try to influence public perception surrounding a voting issue.

The Federal Chancellery does not keep statistics on the number of complaints filed. In general, there is a lack of data in Switzerland on the manipulation of elections, said Andreas Glaser, co-director of the Center for Democracy Aarau (ZDA), told SWI in 2019.

At the same time, the many popular votes in Switzerland on a large range of topics and the small-scale of the issues help to ensure that the stolen election myth has so far not been able to gain a foothold in Switzerland, Blassnig notes.

At the national level alone, Swiss voters have been able to have their say more than 100 times over the past ten years.

To ensure that the situation never goes that far, the Zurich-based researcher recommends increased and targeted investment in education and the media. “This includes the competent use of digital media and the existence of strong public service media,” Blassnig says.

However, she doubts Switzerland will rigorously regulate its social media, as is currently being debated by the European Union. “On this issue, we are traditionally somewhere between the permissive US and the restrictive EU,” said Blassnig. Switzerland relies more on the judgment of individual users than the rest of Europe, but less than America.

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.