The stolen childhood of the factory children

The United Nations has declared 2021 the International Year for the Elimination of Child Labour. Making children work has been outlawed in Switzerland since the 19th century.

During the industrial revolution, children slaved away in Swiss factories to the point of collapse. A political outsider is to thank for the fact that child labour was banned relatively early.

“Workers sought: Two big working families with children capable of work will be well cared-for at a spinning works.” With this advertisement placed in the Anzeiger von Uster gazette, a Swiss factory owner was looking for employees in the 1870s.

It was a matter of course that the children of labourers had to work too. Child labour was nothing new when the first factories opened, but the industrial revolution turned it from a day-to-day reality into exploitation.

Peasants and home-workers saw their children primarily as labourers before the industrial revolution. The family was first and foremost a labour unit; working children were essential for its livelihood.

As soon as a child was old enough, he or she helped out in the farmyard or the workshop. But they were spared the more demanding adult work.

Children usually only performed tasks that were appropriate for their strength. They were not fully-fledged labourers.

Industrial Revolution

Then the wave of industrialisation rolled over Switzerland. In the 19th century, the view that children were labourers survived the change of scene from the farmyard to the factory.

That is where the real exploitation began: in contrast to the farmyards, there was almost no distinction between adult and child labour in the factories. Muscular strength was not required to thread a loom.

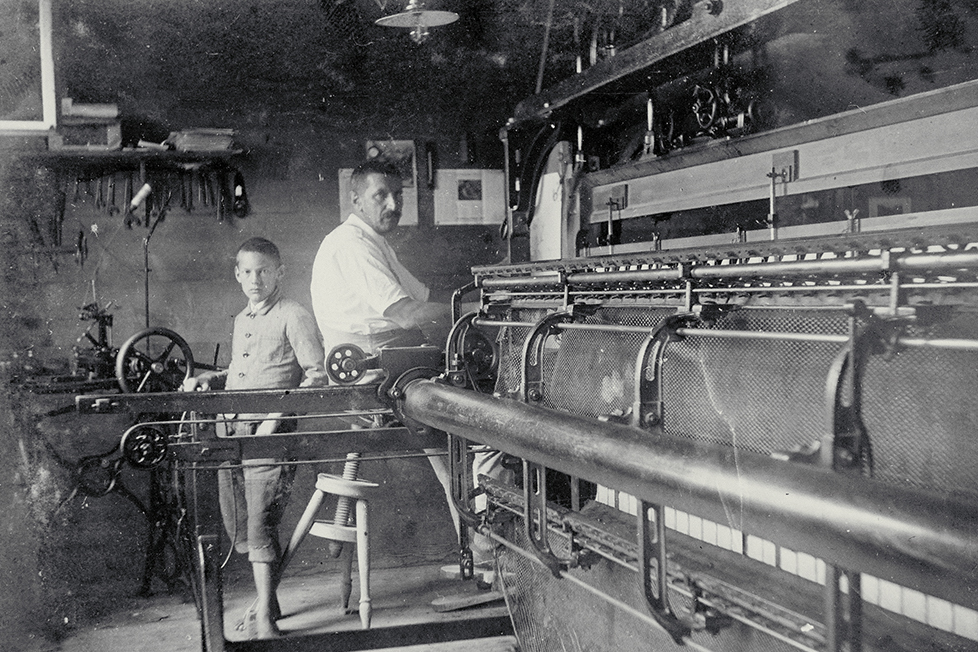

A great number of these “factory children” sat at looms and embroidery machines.

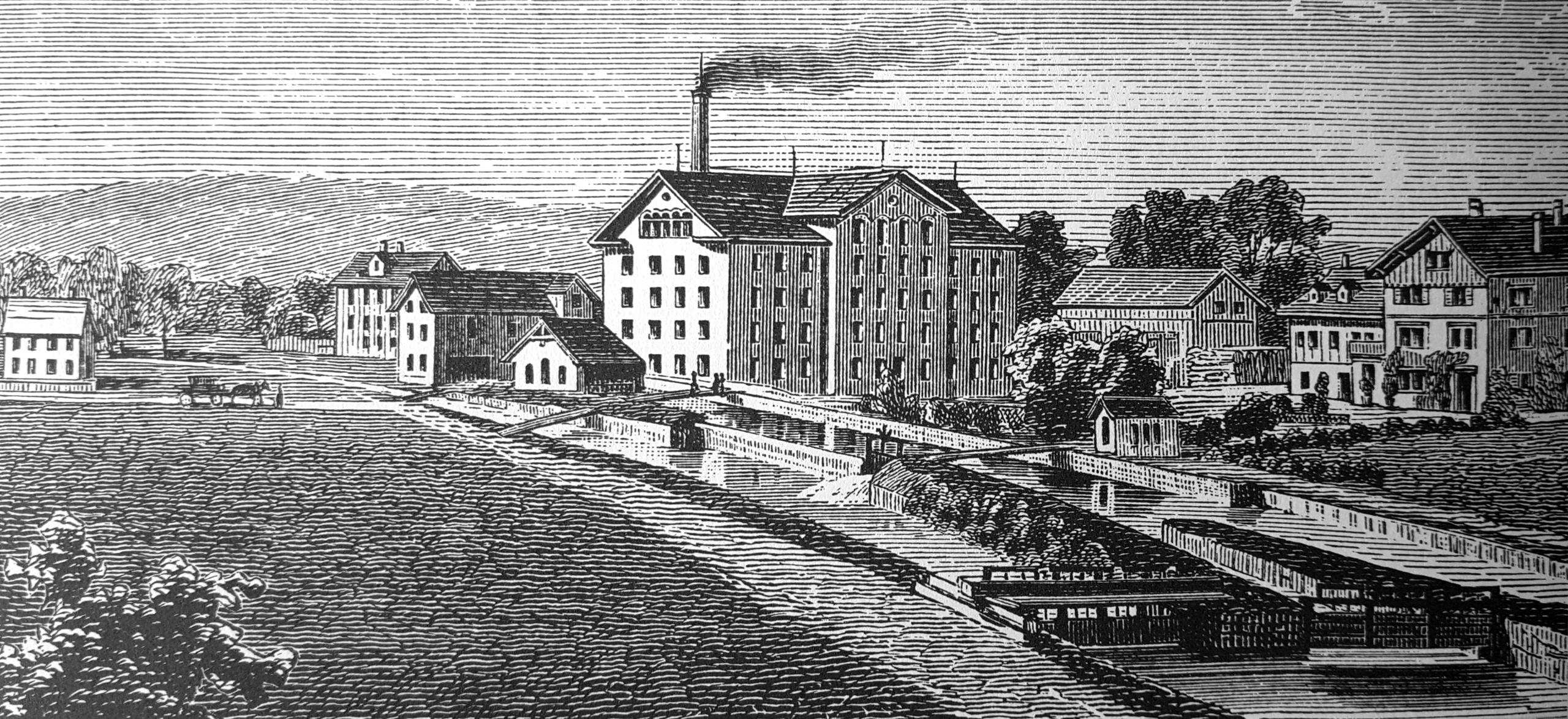

Most Swiss textiles factories were in the east of the country, and outside Zurich. A hub of the textile industry – and of child labour – sprang up along the Aabach river, between Lake Pfäffikon and Lake Greifen. Almost a third of the workers in these factories was under the age of 16.

Some families had their own loom or embroidery machine at home, and worked for the big textiles manufacturers. Children were also employed as labourers in the home.

From dawn to dusk

The destinies of the sons and daughters of a family of textile labourers were sealed early on, whether in a factory or at home.

In practise, they had no chance of following their own desires. Early in their childhood, they spent most of their time on monotonous work at home or in the factory – they were seldom at school and had no play time at all.

Some children were already employed to thread embroidery needles at the age of six.

In those days, threading the machines was a time-consuming job that required little fingers, and was therefore primarily carried out by women and children.

If these children reached school age, it was normal that in addition to their schooling they spent as many as six hours a day threading – early in the morning before school, at lunchtime and after school, deep into the night.

Economic factor

Of course the heavy workload had an effect on children’s health. Inspectors noticed the hunched backs, the bad eyesight and the tired listlessness of the children.

In 1905, a pastor from canton Appenzell-Outer Rhodes wrote that overburdening child labourers had led to “their being tired, sleepy and subdued; they are both mentally and physically weak, they are inattentive and sit there absently, showing no interest – their attention is elsewhere, they are elusive and indifferent.”

The exploitation of children was systematic, but it didn’t happen merely as a result of malevolence or ignorance.

Low wages meant that families often needed the additional income. On top of that, in the families of labourers, craftsmen or peasants at the turn of the 20th century, children had a completely different status from today. Parents still saw them primarily as workers.

For businessmen, this was convenient – the children provided especially cheap labour. Many liberally minded citizens defended child labour with economic arguments.

Victor BöhmertExternal link, an important economist of that time, wrote that the spinning works “must ideally take advantage of child and female labourers at low wages” to compete with foreign rivals.

External criticism

Towards the end of the 19th century, critical voices gained momentum and child labour was recognised as a serious problem.

Even Böhmert, the economist cited above, had his reservations. He described child labour as “the worrying dark side of our modern factories.”

It is astonishing today that criticism of child labour came from the bourgeoisie and not from the working families themselves. The labourers were afraid that they wouldn’t be able to survive without the additional income their children earned.

Although many middle-class politicians recognised the problem, they did little to change anything. It was a political outsider who set the ball rolling.

Maverick with mission

Wilhelm JoosExternal link, a parliamentarian who was not affiliated to any party, delivered the first initiative for a nationwide factory law in 1867.

The Schaffhausen native was known for his engagement to protect the socially weak.

This was a time when such political issues caused heads to shake in many sectors of society.

In his lifetime, he was viewed as an eccentric figure – today he is seen as a visionary politician. When Joos first initiated a nationwide proposal, some cantons already had laws regulating factory work including child labour. But these were often too lax and the rules differed widely.

It took time for Joos’s idea for a law to come to fruition.

But in 1877, ten years after his first motion, Switzerland introduced its first national factory law. Child labour was banned. Switzerland’s first national labour law was one of the strictest in the world. The Social Democrat Interior Minister Hans-Peter Tschudi called it a “pioneering achievement on an international scale”.

Child labour despite factory law

On paper, children should now have disappeared from the factories. But it took some time before the new law was respected across Switzerland.

In canton Ticino, for example, children were still working in factories 20 years after its passage.

It took time, but little by little child labour disappeared from the factories.

In agriculture things looked different; child labour survived until deep into the 20th century. With “contract child labourers,” many farming families kept real child slaves. This dark chapter of Swiss history has only been properly addressed in recent years.

Translated from German by Catherine Hickley

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.