Google design guru Claude Zellweger puts people and nature before technology

In San Francisco, he is one of the heads of industrial design at Google - which also manufactures objects, especially phones. But this native of Meggen, on the shores of Lake Lucerne, is anything but a technology addict. SWI swissinfo.ch met with Claude Zellweger.

“We’re a low-tech family,” Zellweger says. “In 26 years in California, I’ve never had a television, and my children don’t play video games, or at least very rarely.” Zellweger is facing the imposing structure of the Bay Bridge, which links San Francisco to Oakland. On a mild September afternoon, we’re standing next to the Ferry Building, where the boats that cross the bay still dock, and where Market Street, one of the city’s main thoroughfares, begins. Google has opened an office complex in a 43-floor tower here.

With his Californian wife and their 14-year-old twins, Claude Zellweger refuses to “surround himself with technological gadgets” apart, of course, from the indispensable phone. He is, he says, “the exact opposite of a nerd.”

What motivates him above all is “art, design and music, but also people, nature and movement,” he says. Living in the city, he enjoys the little things that he wouldn’t be able to do in Switzerland, like putting on his wetsuit to surf the icy ocean waves before going to work. He gets to work by running, cycling or taking public transport to his design studio in Mountain View, Silicon Valley, near Google’s headquarters. The car, an electric one, of course, is mainly used by the family to go hiking at weekends.

For a full version of the interview, listen to our podcast the Swiss Connection.

From La Tour-de-Peilz to San Francisco, via Pasadena

“I chose the technology industry because it plays an essential role in defining the way we play, learn and communicate,” says Zellweger. Aged 50, he is relaxed and elegant. He says his aim as a designer is to try to help “shape our future – with humility and respect”.

Silicon Valley and Switzerland are both considered among the most innovative areas in the world. Why? What divides them and what brings them together? What can they learn from each other? In this series, we tell you about Silicon Valley through the eyes of the Swiss who experience its temptations, promises and contrasts up close.

His career began in the 1990s in La Tour-de-Peilz, on the shores of Lake Geneva in the canton of Vaud – to be exact, at the Château de Sully, which at the time housed the European site of Art Center College, a design school whose head office is in Pasadena, near Los Angeles. Later, the opulent building became the home of Shania Twain, the world-famous country-rock star.

“Technology plays a critical role in defining the way we play, learn and communicate”

At the time, the best students were given the opportunity to complete their training in California. Zellweger was one of them. At the age of 20, his American dream was to live in a huge urban area, “with a culture and way of life totally different from Switzerland’s”. He is attracted to “places that are so big that whatever your interests or inclinations, you are sure to find people to share them with.”

At first, he had no plans to stay. Then he started working for design agencies. The biggest of these were in San Francisco, so he settled in this city with its temperate climate and a more human scale than that of Los Angeles.

With two friends, he set up his own design agency, which did so well that it was bought by the Taiwanese phone manufacturer HTC after a few years. And in 2016, Zellweger was contacted and hired by Google.

Google culture

Today, he heads the team that designs augmented reality products and Google Pixel mobile phones. Though still little-known in Europe, these phones rank third in US sales, behind Samsung and Apple’s iPhones. In Japan, they even take second place, behind the iPhone but ahead of the Japanese brands.

“Our team has a unique profile within the company,” Zellweger says. Rather than being spread over several sites in different countries, it is concentrated in one studio, which is furnished with materials and objects that the employees have brought back from all over the world. Their mission is “to imagine how we will use technology in the next three to five years, and sometimes even beyond that.” Their aim is “to adapt technological progress to the way people live and communicate, and not the other way round.”

All this comes with famous Google-style working conditions, based on the principle that “if you feel at home in the office, you’ll be more inclined to spend most of your time there.” This ethos has become a model for others, though it has receded a little at Google, which has grown from a start-up in the late 1990s into a multinational corporation with almost 200,000 employees.

For Zellweger, the human landscape at Google is what enriches his job. More than having a games room or fitness centre at the office, “Google represents a true cross-section of society, with very different skills and backgrounds,” he says. It’s a particularly stimulating environment, with a strong appetite for innovation, and “the right to fail and question yourself,” he says.

But that also has a flipside. “People here let their jobs define who they are and how they live. They mix work and personal life, which may make them more relaxed at work, but also less relaxed in their free time,” he says. He says that in contrast, he has remained “rather European” in this respect, keeping work and leisure separate. But that doesn’t stop him from “constantly designing things in his mind,” whether he’s running in nature or busy in the kitchen.

Artificial intelligence for everyone

With his mission to anticipate the future, Zellweger should be in a good position to sense what “the next big thing” will be. Unsurprisingly, like most people who work in tech or follow it closely, he names technologies to combat global warming and artificial intelligence. “Unlike the metaverse or web 3 or 4.0, where people are still wondering what use they will have in their lives, AI is a technology everyone can already use,” he says.

Since the launch of conversational robots such as ChatGPT and Google Bard, everyone can see that, despite its imperfections, AI has entered our lives. In fact it has already been there for some time, but discreetly, whether it’s recommending internet content, controlling our vacuum cleaner, braking our car or adjusting the settings on our phone when it takes a photo.

Zellweger is keenly aware of the limits and dangers of a technology that is still in development, but he sees AI as “a new collaborator that we bring to the table and that can have a different point of view and help us weave together a creative vision.” What’s more, AI can spare humans from certain tedious and repetitive tasks, leaving them to concentrate on “what makes us more human,” he says.

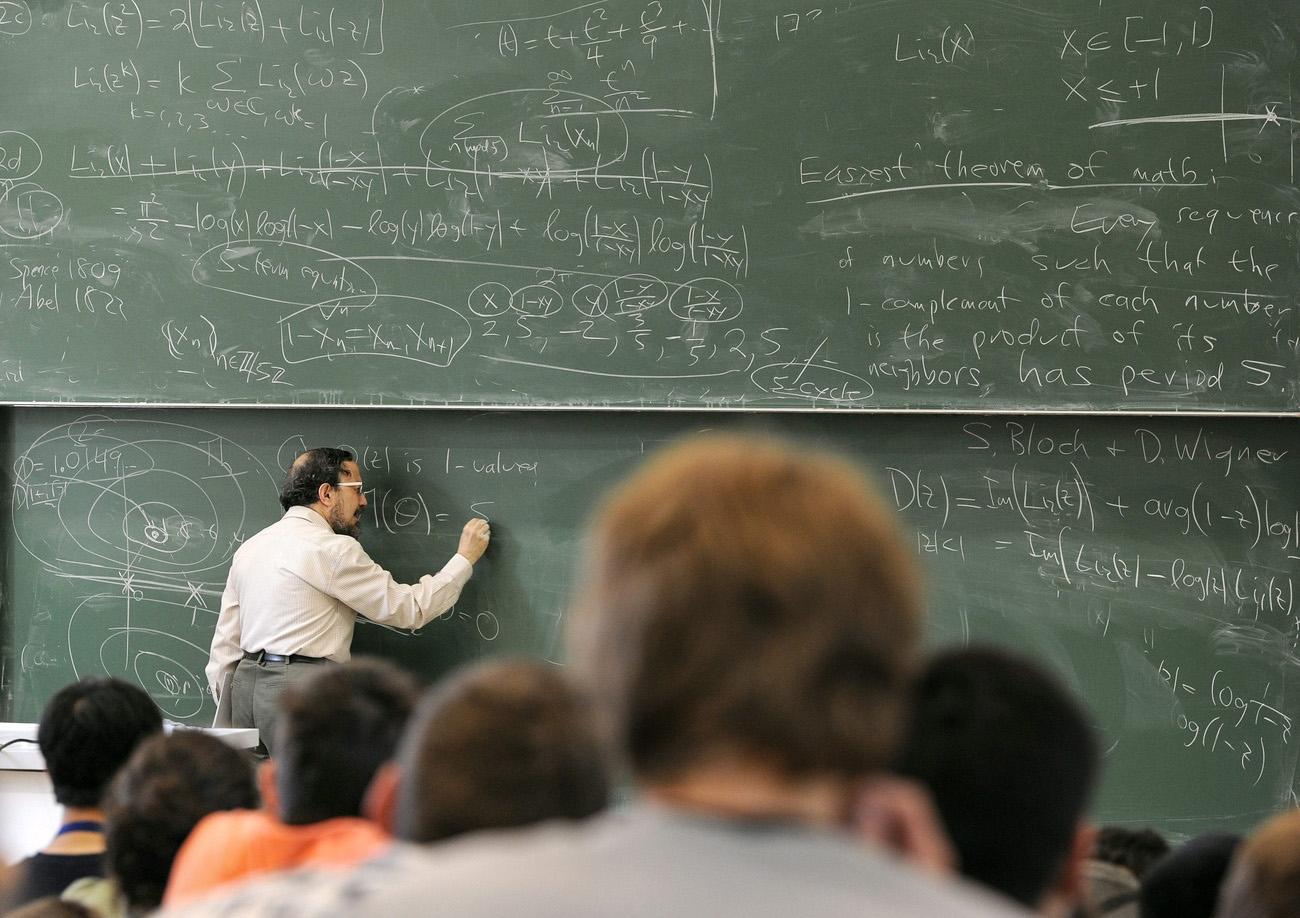

Of course, we’ll also have to deal with the challenges posed by robots that act as if they were thinking. Particularly at school. “Many teachers have already realised they can’t ignore the presence of AI,” he notes. And to prevent pupils or students from using these machines to get out of doing work themselves, we’re going to have to “integrate them into schools and recalibrate the entire education system. And that’s going to take years,” he says.

Home, sweet home

In San Francisco, which is now his home, Zellweger particularly appreciates “the ease of contact with the people, the multiculturalism, the progressive side and the fact that nobody judges you,” as well as “the majestic landscape.”

But faced with the, sometimes chaotic, reality of the big city on the bay, he admits that Swiss cities are better organised, for example in social terms and in terms of public transport.

So even though he has almost become Californian, he is convinced that one day he will live in Switzerland again. “Going back four weeks a year isn’t enough,” he says.

Translated from French by Catherine Hickley

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.