Politics and the potential of nostalgia

Once described as a Swiss sickness, nostalgia has become a powerful weapon in the hands of politicians from Trump to Putin to Brexit proponents. The more we understand nostalgia and its Swiss beginnings, the more we understand one reason why populist movements are riding high.

Nostalgia was considered largely a Swiss illness up until the 19th century, and cures included moving a patient to high ground, since at the time it was believed the ‘illness’ mostly affected Swiss mercenaries fighting for armies across Europe’s lowlands. These soldiers were said to be unaccustomed to the difference in air pressure from their beloved Alps. If their nostalgia wasn’t cured, it could lead to death.

Nostalgia, a Greek compound word, was translated into German as ‘Heimweh’, and thus homesickness in English. Today, instead of a longing for the familiarity of home, nostalgia is, according to the Oxford dictionary, a sentimental longing for a period in the past.

Nostalgia – Swiss origins

It was Swiss doctor Johannes Hofer who in his dissertation in 1688 described it for the first time as a sickness, and introduced the word nostalgia. Another Swiss in his dissertation a few decades later even asserted that the sound of the melody (Kuhreihen in German or Ranz des Vaches in French) sung by Swiss farmers to call their herd of cows together was so strong it could lead to Swiss mercenaries deserting.

Hofer believed it was a suffering caused by being torn away from familiar surroundings which could only be healed by returning to the homeland. Zurich scholar Johann Jakob Scheuchzer argued it was caused by air pressure, which was higher in the low countries of Europe compared with the Alps and therefore impeded the blood circulation of the Swiss who, he said, lived on the “upper summit of Europe”. Scheuchzer believed relief could only be had by relocating sufferers to high ground.

In an encyclopedia published in Switzerland in 1774, Albrecht von Haller considered the melancholy caused by nostalgia could weaken a person, make him sick, even lead to death. An 18th century rumour had it that Swiss soldiers in foreign armies faced the death penalty if they were caught singing the Kuhreihen.

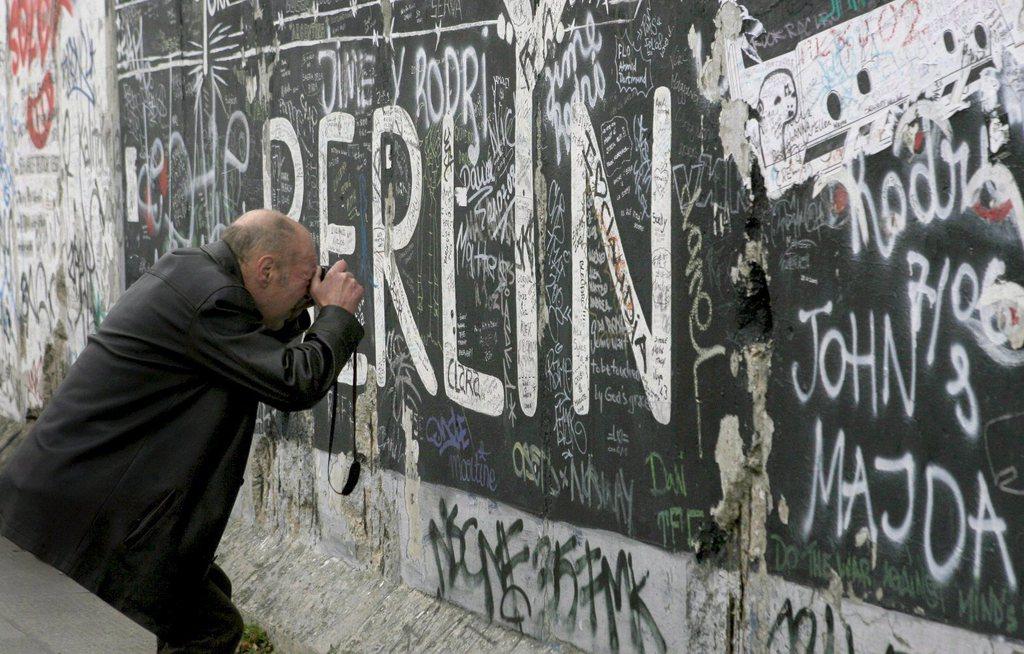

It can be argued that Donald Trump and Vladimir Putin, along with populist movements across Europe, enjoy fighting on the proverbial ‘lowlands’, to keep voters nostalgic for ‘better times’.

These are seen in the campaign slogans of leading Brexiters like Nigel Farage and his UKIP party, “We want our country back”, or Donald Trump’s “Make America Great Again”, or how Switzerland’s conservative right, Swiss People’s Party, capitalises on the past. As part of its anti-immigration campaign, the party claims: “At one time, Switzerland was one of the safest countries on earthExternal link”.

In Russia, a majority of Russians would like to see the Soviet Union restored, according to the Levada Center independent polling instituteExternal link. Putin’s military moves to annex Crimea and his support of rebels in eastern Ukraine are not surprising when one considers the Russian leader’s 2005 speech in which he regretted the collapse of the Soviet Union and the fact that “tens of millions of our co-citizens and co-patriots found themselves outside Russian territory”.

Old-fashioned values

In politics, the nostalgia card is most effective when played for an older audience. A Russian television channel called ‘Nostalgia’ is mainly popular with middle-aged menExternal link, born during the height of the Cold War (1950s to 1970s). In the UK, a pre-Brexit poll showed 54% of over 55s supporting the ‘Leave’ campaign, with only 30% in favour of remaining. “Getting out of Europe would mark a return to more old-fashioned valuesExternal link,” wrote Geoffrey Edwards from the University of Cambridge, trying to understand the reasoning of older voters.

In Switzerland, the People’s Party – the country’s largest political party – has been accused of glorifying a time in the past when women stayed at home and men were the sole breadwinners. In a 2014 campaign to buy new fighter jets to replace the current 30-year-old fleet, the party’s Ueli Maurer, then Swiss defence minister, compared the jets with household articlesExternal link, arguing that one gets rid of old items. One of the only old articles left in his home, he smiled, was his wife whose job it is to take care of the house. Instead of being met with a backlash of complaints forcing the People’s Party minister to apologise, the joke was greeted with laughter at the well-attended events he addressed, encouraging Maurer to repeat it.

When things were better

Whether Putin, Trump, Brexiters or Switzerland’s People’s Party, politicians are playing on a weakness that middle-aged and older voters have for a perceived bygone era. Our ageing brains tell us that, according to our remembered experiences, things were better when we were younger.

Volumes of research has been published on this phenomenon, which is known as the ‘reminiscence bump’. This describes the fact that older people have a greater recollection of memories from their adolescence and early adulthood than any other period in their lives.

There are explanations why this may be so: our ability to store memories is at its greatest during our teens and early adult years. This is also a period when we experience many firsts.

And we have a better recall of positive events, a fact that can be exploited by politicians. One explanation for having happy memories of our life between the ages of 15 and 30External link is because this is when we leave home, finish our education, get our first job, get married and start a family. It’s thought negative events could be suppressed by a built-in defence mechanism.

Once considered a disease by 17th century Swiss doctor Hofer, nostalgia’s health benefits are now being touted. Greek professor Constantine Sedikides and fellow researchers claim that “nostalgia may facilitate use of positive perceptions about the past to bolster a sense of continuity and meaning in one’s lifeExternal link”. And it is being used to treat people with dementia in various countries, including Switzerland.

But when it comes to the serious business of politics and casting our votes to decide the future of our countries and their place in the world, we should be reminded that all was not better, once upon a time.

Do you think things were better when you were a young adult, wherever you were living at the time? We’d like to hear from you.

Follow the author on Twitter @dalebechtel

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.