Explainer: why should we care about science diplomacy?

Geneva has just welcomed 1,000 scientists, academics, diplomats, business leaders and members of civil society for discussions around science diplomacy at the GESDA summit, which wraps up on Friday. Topics included longevity and artificial intelligence. SWI swissinfo.ch takes a closer look at science diplomacy and the role it plays in Switzerland’s foreign policy.

What is science diplomacy?

Many of the major challenges of the 21st century, such as climate change, food security, pandemics and the risks of artificial intelligence have scientific aspects, and science plays a crucial role in addressing them.

Recognising the potential impact of science on global affairs and the need to come up with solutions, several countries including the United States, the United Kingdom, Japan and Switzerland have created posts of science advisors within their foreign ministries. Some have also posted science attachés to key embassies.

Since 2010 science diplomacy has a formal definition made up of three pillars:

- Science for diplomacy: science as a soft power tool to improve international relations.

- Science in diplomacy: using scientific evidence to inform foreign policy.

- Diplomacy for science: using diplomacy to support international scientific collaborations.

Science diplomacy is any one of the three, or a combination of two or three pillars.

A Swiss scientific and diplomatic project to safeguard and study the Red Sea corals, which are particularly resilient to climate change, has resumed in Sudan after a brief hiatus. SWI swissinfo.ch met the project’s leader, Anders Meibom of the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology Lausanne (EPFL).

Swiss ambassador Alexandre Fasel explains how rapidly evolving scientific discoveries will change the face of the world.

Swiss Foreign Minister Ignazio Cassis is trying to give the country’s foreign policy a new twist, including getting more involved in science. Here he argues for development of a cross-cutting field called “Science Diplomacy”.

What are the major successes of science diplomacy?

CERN (European Organization for Nuclear Research), created in 1954, is often considered a success story of science diplomacy. Initially the institute launched by 11 countries aimed to conduct research in atomic physics through international collaboration. Today it includes 23 countries ranging from the UK to Israel and Hungary. CERN made possible some of the first contacts between Israeli and German scientists after the Second World War. However, Cédric Dupont, Professor of International Relations at the Geneva Graduate Institute, argues that “it is an overstated example of science diplomacy. Whether it is about science diplomacy or purely scientific research is an open question.”

As opposed to the fight against fossil fuels, which has yet to reach international consensus, the battle against the hole in the ozone layer and the chemicals contributing to it is another example of successful science diplomacy. The Montreal Protocol, adopted in 1987, is one of the rare treaties to achieve universal ratification. The protocol is a multilateral agreement that regulates the production and consumption of nearly 100 man-made chemicals referred to as ozone-depleting substances.

Science diplomacy also paved the way for the signing of the Antarctic treaty in 1959. The treaty protects the region from military activities and the exploitation of mineral resources.

Another well-known example is the IPCC, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, established by the World Meteorological Organisation (WMO) to provide policy-makers with a scientific view of climate change. Its reports, released every six or seven years, provide key input for international negotiators to tackle climate change.

What are the major challenges facing science diplomacy?

Achieving scientific consensus takes time – years, decades and sometimes centuries. “During the time leading up to a consensus, if you offer many scientific opinions to diplomats, it is hard to think that they will converge on anything,” says Dupont. “The first 20 years of the IPCC’s work was undermined by that. Some scientists managed to throw a spanner in the works, by claiming they were not convinced about human-caused climate change.”

Another challenge is that research funding is anything but neutral, he argues. “Very little scientific research has been done in certain domains, due to the lack of interest from the main economic powers, the Global North. Therefore, diplomats will not get involved, simply because there is no science available. Funding of science follows trends and politics. Lots of countries in the world have very limited research capacity, so there is a risk of imposing the research agenda of the North on global politics.”

Another challenge to overcome is a misalignment between the time horizon of scientists and politicians. “Politicians tend to think short-term, while a lot of research in natural sciences is carried out in the long-term,” says Dupont.

“Lastly, how much science remains once you have gone through the cycle of international discussions is a question,” he says. “The IPCC report, for example, puts increasing pressure on states, although probably not enough yet, as politicians have been able to push back so far. But without the IPCC report, we wouldn’t know what’s going on.”

Is Geneva a centre for science diplomacy?

Geneva is home to many international organisations that focus on science such as the IEC (International Electrotechnical Commission), ISO (International Organization for Standardization), ITU (International Telecommunications Union) and WIPO (World Intellectual Property Organization). Nonetheless experts argue that these entities cooperate technically on issues such as standards and patents rather than innovate or use science as a solution to global problems.

“Science diplomacy is another level,” says Dupont. “It involves more fundamental research in science that gets to reframe the discussions at an international level. That’s what we mean by science diplomacy. Geneva has potential to become a centre for science diplomacy, but I don’t think it is there yet.”

How does science diplomacy fit into Swiss foreign policy?

Switzerland’s aim is to position International Geneva as a leading hub for discussing digitalisation and technology and finding solutions to challenges these issues raise.

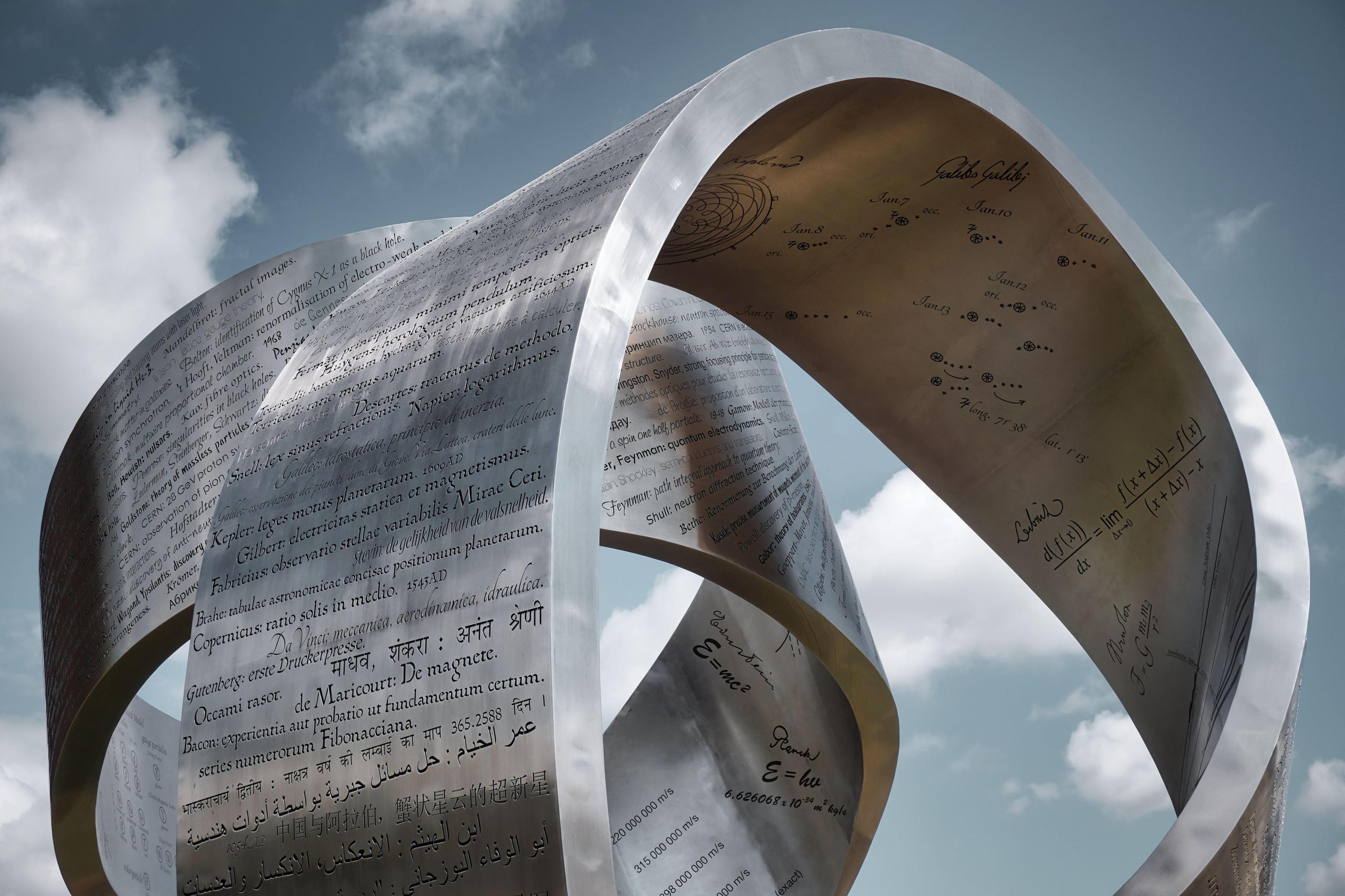

This allows the country to pull some weight on the international scene while maintaining its neutrality. With this in mind, the Swiss government and the canton of Geneva created GESDA (Geneva Science and Diplomacy Anticipator) in 2019 with the purpose of positioning the city as the world stage of science diplomacy. Its mission is to bring together different communities to anticipate scientific and technological advancements and, based on these, develop solutions for a sustainable future.

“The objective of the Swiss government is to keep International Geneva as a vibrant place for international cooperation,” says Dupont. “But this is not guaranteed. If multilateralism is under threat, there is no guarantee that Geneva can keep it forever. Therefore, you have to continue investing in it.”

Edited by Virginie Mangin

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.