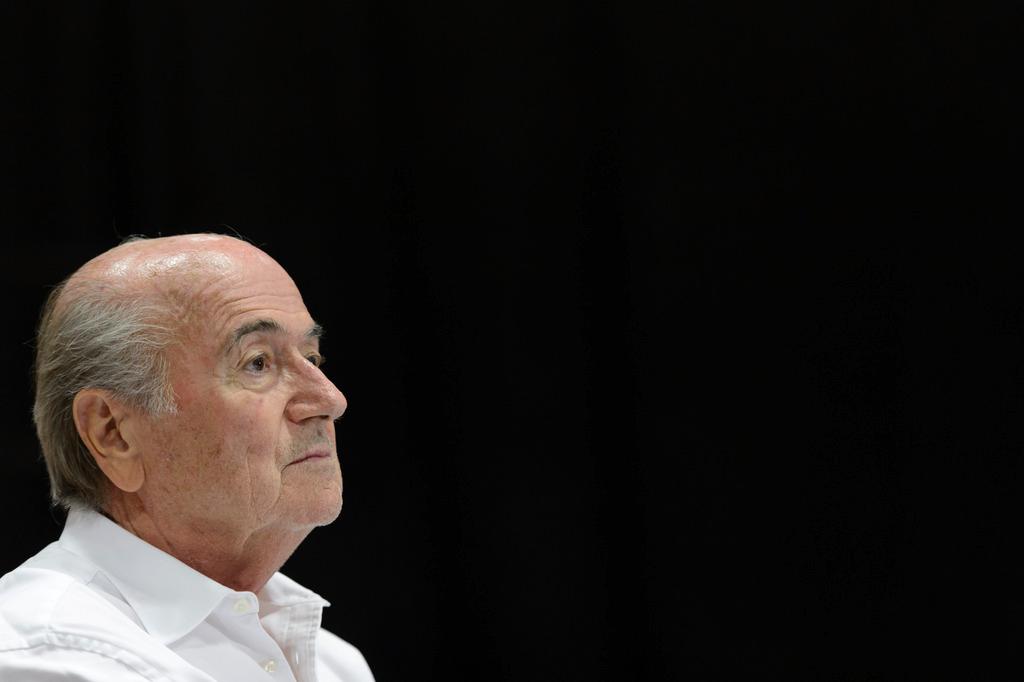

Lunch with Sepp Blatter

Sepp Blatter likes to start the day just before 6am. He skips breakfast but drinks a cup of coffee and does a little dance to stay in shape. "Rhythm, rhythm of life is very important. Also in football, but everywhere," he says.

But on May 27, 15 minutes after he woke up, his morning routine was broken by a phone call. Swiss police, acting on extradition requests from the US Department of Justice, launched a raid on Zurich’s Baur-au-Lac hotel and arrested seven senior FIFA officials on suspicion of taking more than $100m of bribes between them.

The arrests, which were followed by another raid on FIFA’s headquarters on a hill above Zurich, came as hundreds of football officials were gathering in Switzerland for an election to choose a new FIFA president. “I felt like a boxer who was just going into round 12 and said, ‘I’m going to win.’ But then: BONG!” says Blatter, 79, mimicking a knockout blow.

The effect was seismic: although the vote went ahead two days later, and Blatter was re-elected for a fifth term, he stepped down the week after, claiming he needed to “protect FIFA”. It was not enough. Swiss prosecutors put Blatter under investigation and, on October 8, he was suspended from all football activities and evicted from his office at FIFA. While you can physically remove Blatter from FIFA’s headquarters, separating the man from the organisation he has built in his image for the past 40 years – first masterminding football programmes in Africa, then becoming general secretary and finally president – is a tricky proposition.

More

Financial Times

External linkWe meet at Sonnenberg restaurant, which in its literature describes itself as the “FIFA Club”, run “under the patronage of Joseph S Blatter” and as a place “where football fans from the worlds of Swiss business, politics and sports meet with their guests for business lunches, exquisite dinners and networking”. I arrive early but Blatter is already waiting, chatting to the restaurant’s head chef, whose white jacket is embroidered with FIFA’s blue logo. We are ushered into a private room with magnificent views over vineyards, then over the city and all the way down to Lake Zurich.

More

The colourful world of Sepp Blatter

The door shuts behind us and there is an awkward silence. The man who has served for years as a lightning rod for so many shocking accusations of corruption and backroom-dealing suddenly seems frail as he fidgets with his cutlery and rubs his hands together. It turns out that he has a great deal to get off his chest, and several grenades to toss into the fragile process to find his successor, but it is difficult to know where to begin.

We clink glasses of a Swiss sauvignon blanc and I ask him how he feels now that the end is in sight. In February, he will permanently leave FIFA after a fresh presidential election. Others have told me that it will be an existential crisis for Blatter and hinted darkly that he may not be able to bear it. He freely admits that he is a monomaniac who cannot, and will not, stop thinking about FIFA.

He lives alone in an apartment in Zurich and works from a “very small” office with a desk, a computer, a football and a picture of the Matterhorn on the wall. “I regret I cannot go back to my office [at FIFA HQ], because my office [there] was a little bit more than an office; it was the ‘salon’ we were living in,” he says in accented and slightly topsy-turvy English (he is most comfortable in German or French but also speaks Italian and Spanish).

Blatter still wakes early, however, and scans the news for any developments about FIFA. “I answer my personal mail; there is a lot of mail. I am following very carefully what is happening in the office of FIFA and around this office. For the time being, I have not had any possibility to say, ‘Now I go a few days on holiday’,” he says. “I am following everything. I cannot just say I switch off because I am not any longer in the office. Because my office is my memory,” he says, tapping a finger to his forehead.

A waiter enters with a treat from the head chef: plates of salmon, cucumber and caviar. But Blatter is allergic to seafood, he says, shooing the dish away. “They know this. I do not know why they serve it.” He orders cured beef instead, which he eats with his hands, together with some bread.

As we settle into our conversation, he quickly pinpoints the moment when FIFA’s troubles – and his downward spiral – began. “It is linked to this now famous date: December 2, 2010,” he says, referring the day he pulled Qatar’s name out of the envelope as host of the 2022 World Cup.

More

FIFA and Sepp Blatter: Where will it end?

“If you see my face when I opened it, I was not the happiest man to say it is Qatar. Definitely not.” The decision caused outrage, even among those who do not follow football. “We were in a situation where nobody understood why the World Cup goes to one of the smallest countries in the world,” he says.

Blatter then drops a bombshell: he did try to rig the vote but for the US, not for Qatar. There had been a “gentleman’s agreement”, he tells me, among FIFA’s leaders that the 2018 and 2022 competitions would go to the “two superpowers” Russia and the US; “It was behind the scenes. It was diplomatically arranged to go there.”

Had his electoral engineering succeeded, he would still be in charge, he says. “I would be [on holiday] on an island!” But at the last minute, the deal was off, because of “the governmental interference of Mr Sarkozy”, who Blatter claims encouraged Michel Platini to vote for Qatar. “Just one week before the election I got a telephone call from Platini and he said, ‘I am no longer in your picture because I have been told by the head of state that we should consider . . . the situation of France.’ And he told me that this will affect more than one vote because he had a group of voters.”

Blatter will not be drawn on motives. He says he has only once spoken to Sarkozy since the vote and did not raise the issue. He does admit that the vote for the World Cup, carried out by a secret ballot of FIFA’s executive committee, was always open to “collusion”. “In an election, you can never avoid that, that’s impossible . . . when you are only a few in the electoral compound.”

One month after FIFA’s 22-strong executive committee voted 14-8 in a secret ballot in Qatar’s favour, the Arab state announced that it had begun testing French Dassault Rafale fighter jets against rival aircraft for a fleet upgrade. In April 2015, Qatar bought 24 of the jets for $7bn, with an option to buy 12 more.

The waiter arrives with our “FIFA salad”, a mix of lamb’s lettuce, croutons, lardons and diced egg. “This is Mama Blatter’s salad,” Blatter says cheerily. “We always made it with whatever greens were in season, and you put some croutons and a little bit of bacon.”

Blatter is from the small Alpine town of Visp (population: 7,500), about two hours from Zurich by train. A Roman Catholic, he plans to return there this weekend for All Souls’ Day. His father worked in a chemical plant and his only daughter, Corinne, still lives there, teaching English. He has a 14-year-old granddaughter called Selena. Blatter admits that his troubles have hit her hard. “I think she was suffering more than me,” he says, indicating that he lets criticism wash over him while she takes it personally.

When I ask Blatter what he thinks of Platini, he sits back in his chair, pauses, and then gives a diplomatic, if strained, response. “Platini was an exceptionally good player. He is a good guy. He could be a good successor, yes. It was foreseen, once, that he shall follow [me].”

Platini is still in the race for the FIFA presidency, but his campaign was effectively derailed following his suspension, at the same time as Blatter, after a CHF2 million ($2 million) payment from FIFA to his bank account in 2011 came to light. “You do not need to have a contract written down [ . . .] according to Swiss law,” Blatter says of the Platini payment, adding that even witnesses are not necessary. “Handshake contracts are valid. The Anglo-Saxon system is not the same as the system here in central Europe.”

He is correct – Swiss law does provide for oral contracts – but I point out that this is not the way that large companies behave. “But we are a club,” he responds. When I point out that the payment was not accounted for, he shuts down the conversation.

While Blatter pays lip-service to the idea of reform at FIFA, saying there “must be more than a few changes”, he remains brass-necked about the culture of handshakes, favours and secret deals that he encouraged. “The system is not wrong,” he says, adding that if he had been allowed to remain as president, “then we would be in the right way”. His successor, he believes, should not try to change what he has created.

I ask him about the money, the allegations of bribery and corruption that have dogged him for years. Did he, or people working on his behalf, ever hand out cash to win the support of FIFA’s members?

He invokes his parents as he denies it all. “We have a principle in our family. The basic principle is to only take money if you earn it. Secondly, do not give money to anybody to obtain the advantage. And the third one is if you owe money, pay your debts. These are the principles I have followed since [I was] 12 years old,” he says. “That is why I am claiming that my conscience, as far as money is concerned, I am totally clear and clean.”

Is he a rich man? No, he says, he only earns what FIFA pays him – a sum that he refuses to disclose because FIFA releases its leadership payments only in aggregate; last year it paid $39.7 million to its “key management personnel”.

“What do I do with my money? My daughter has an apartment. I have an apartment, one here and one there. That is all. I am not spending money just to show I have money. If you look at the richest Swiss people, I cannot approach the richest 3,000, because they are up to $25 million.”

The waiter returns with our main courses. For me, a surprisingly large veal chop; for Blatter, a plate of boiled beef and julienned vegetables. He picks at it slowly. “I have to tell you that I don’t eat so much because you cannot eat more than you burn,” he says.

After a pause, he sketches out what he thinks were his two main achievements at FIFA: the Goal project, which sends millions of dollars to the world’s poorest countries and claims to have built more than 700 football facilities since 1998, and the decision to rotate the World Cup around the continents and, especially, to bring it to Africa in 2010.

He bats away my suggestion that the development money was another way of distributing favours and was a source of money for corrupt officials: “There is a percentage, perhaps two per cent or three per cent, which have not worked.”

His success in maintaining an iron grip on FIFA hangs partly on the support of African countries, which he has courted assiduously. The shadow of colonialism still lingers, and African football officials often feel that Europeans treat them as second-class. Blatter, by contrast, is unwavering in his vocal support for African football and worked tirelessly to bring the World Cup to South Africa. He has also delivered commercial success: in the four years leading up to the 2014 World Cup in Brazil, FIFA had total revenues of $5.72 billion.

In his view, he has created a virtuous circle: FIFA helps kids in developing countries play football by building them pitches and then benefits when they get home and watch big matches on TV. This work, he insists, cannot be undone: “My reputation is spoiled, because I was bitterly attacked, as responsible for everything. But it will not damage my legacy.” With the benefit of hindsight, he wonders whether it might have been better for him to stand down after the high of the 2014 World Cup in Brazil.

When I ask about the ISL case, in which it was revealed in 2008 that a sports agency founded by Horst Dassler of Adidas had paid CHF138 million in bribes to senior FIFA officials, Blatter refuses to discuss it. He was not found guilty of any wrongdoing and, he says, the case is now closed and jokes about double indemnity: “In American law it is said you cannot be condemned twice!”

I bring up the case in the US in 2006 where FIFA paid a $90 million settlement to MasterCard for reneging on a contract in order to sign a more lucrative sponsorship deal with Visa. “We were not very very clever,” admits Blatter. “It was wrong. But sometimes, because you were working hard you make mistakes. You cannot just hang somebody.”

More

How the army shaped Sepp Blatter

As we pass over the thorny questions about his wealth, about FIFA’s corruption and secrecy, Blatter is calm. He believes he is a man more sinned against than sinning, and he repeats that he has little control over the behaviour of FIFA’s executive committee, whose members were not appointed by him, but by the six continental football federations.

“Regrets? I do not regret,” he says. “The only regret I have is that in my life in football I am a very generous man in my thoughts and I think people are good and then I have realised that most of the time I was, let’s say, trapped by people. You trust someone 100 per cent and then you see that all this trust was just to get some advantage. I have done it not only once, I have done it more than once. I have to bear that and I bear it.”

Meanwhile, he lambasts Switzerland for not protecting him. “I am a Swiss citizen. I was even a soldier! I was the commander of a regiment of 3,500 people. I served my country!” he protests, referring to his service in the 1960s as colonel in command in the army’s supply unit during the cold war.

These days, he has few allies left. He says he counted on one hand the number of friends he could call on for help when deciding whether to step down after years at the top of football. He admits his reputation has been destroyed. But he cannot stop. He remains proud of his life’s work. “Could somebody else have done it? If he was fool enough to only live for football, then he could have. But it is difficult to find people that have been in the game with not only their body, not only their mind, or with their heart, but with their soul. And I was therein. And if you ask me what I am doing later, I am still therein.”

We do not order any dessert, simply a cup of espresso and some petits-fours in the shape of small footballs. Blatter is looking forward to the evening, when his girlfriend, Linda Barras, a 51-year-old with two children, is flying in to see him. She lives in Geneva, but Blatter is happy with the situation.

“The distances are not detrimental to a good understanding,” he says. “Perhaps it is even better for the guy who has devoted all his life to football. When you are 100 per cent in your job and your job is really something you believe in, then obviously even by being a generous man, at a certain time the person living with you cannot be happy,” he says.

Then he stands up, suddenly small and frail again, signs a football for the restaurant’s manager and disappears into a black Mercedes.

Copyright The Financial Times Limited 2015

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.