Going on a quest for a Swiss passport – as a Swiss national

Born to Swiss parents, Cate Riley was adopted by an Australian family in the 1970s. She has now embarked on a journey to find her roots and be recognised as a Swiss citizen.

Two teenagers and their father are milling about Basel’s main train station, waiting for their mother. Cate Riley appears on the escalator, winking at her kids, cheerful despite the temperature shock the family must be feeling. They have just flown in from Australia, a 17,000-km journey.

“We had to buy warm jackets and shoes,” says Riley. “We never need anything like this back home.”

Riley, her husband Rob and their two children, Ginny and Oscar, hop on a train that will take them to Delémont, the capital of Jura, her father’s home canton.

“He spent most of his youth there,” she explains.

Riley is an Australian citizen, but her roots are in Switzerland. On this trip to Europe, she wants not just to retrace her parents’ footsteps, but also to gain Swiss citizenship. The 52-year-old wants to officially become what she has been since birth: a Swiss national. However, her mission is not as simple as it sounds.

‘The right parents for a red-haired baby’

That’s because Riley was adopted. She was born in Sydney on September 5, 1970 and given the name Margrith. At the time adoption was booming in Australia – 10,000 children were adopted in 1970 alone. The authorities were urging single mothers to give up their babies – society took away the possibility for them to care for their children on their own.

Cate’s biological mother, a single woman who had emigrated to Australia, had no other choice but to give up her daughter, who was the product of a brief relationship.

“These young mothers were expected to forget about their children and carry on with their lives as if nothing happened,” says Riley.

Riley came to her new family at one month old. Her adoptive parents lived in a suburb of Sydney and gave her the English name Catherine Nicole.

“After I was born, it took the authorities one month to find the right parents for a red-haired baby,” she says. Riley was brought up together with her brother, her adoptive parents’ biological child, who was nine years older.

She went to school with other adopted children: “We never talked about it, but it created a bond between us.” Despite being mocked about her situation, Riley had a good childhood. But she never lost her desire to find out more about her origins.

“My adoptive family and I never had that natural closeness,” she says. Riley longed for a deeper connection.

But she felt conflicted. She wanted to remain loyal to her adoptive parents. She did not want to hurt them with her curiosity, aroused time and again, such as when relatives gave her presents for her birthday. The gifts, like a cuckoo clock, had clearly come from Europe, like Riley herself. It was never a secret that Riley’s biological parents were not from Australia.

Finding her biological mother

Even though Riley was keen to find out more about her parents, she was unable to do so. Australia did not allow access to adoption records until 1991, a year that marked the end for the country’s secret adoptions. A change in law enabled Riley, who was 21 at the time, to finally consult her entire file.

“I was completely surprised to find out that I was Swiss,” she says.

Information that would be two clicks away on the Internet today took Riley a long time to find, as she tried to learn more about her parents’ birth country and its people. She got in touch with the Swiss national tourist office. “I didn’t even know where Switzerland was,” she says.

Finding her biological mother turned out to be a real odyssey. “I rummaged through telephone books, visited libraries and contacted authorities,” she remembers. But she could not find anybody in Australia with her mother’s name. “I was close to giving up several times.”

But one day, Riley came across a woman who had the same surname as her mother. “I wrote her a letter and asked her whether she knew my mum,” she says. It turned out to be her mother’s twin sister. “My aunt then forwarded the letter to my mum.”

After five long years of searching, Riley had finally found her biological mother. The two exchanged letters for a few weeks until Riley, who was 25, flew to Brisbane, where her mother lived with her Australian husband and their two children.

Art in her DNA

“She was very happy and grateful to have me back in her life,” says Riley. Margie, as she calls her mother, told her that she had never forgotten about her, but that her hands had been tied. According to Australian law, she was not allowed to look for her daughter.

When Riley met her mother for the first time, she immediately felt welcomed into her newly discovered family. She learnt that her Swiss father had left Australia before she was born, and found out more about her relatives in Switzerland.

“They even came to Australia to meet me,” she says. Her father had not forgotten about her either, but it took him a few years to tell his “second” family about Riley’s existence.

The new situation was difficult for Riley’s adoptive mother. “She was afraid of losing me to my biological mother,” she says as she sketches the snow-covered houses of Delémont from a café where she, her husband and their children are sipping hot drinks.

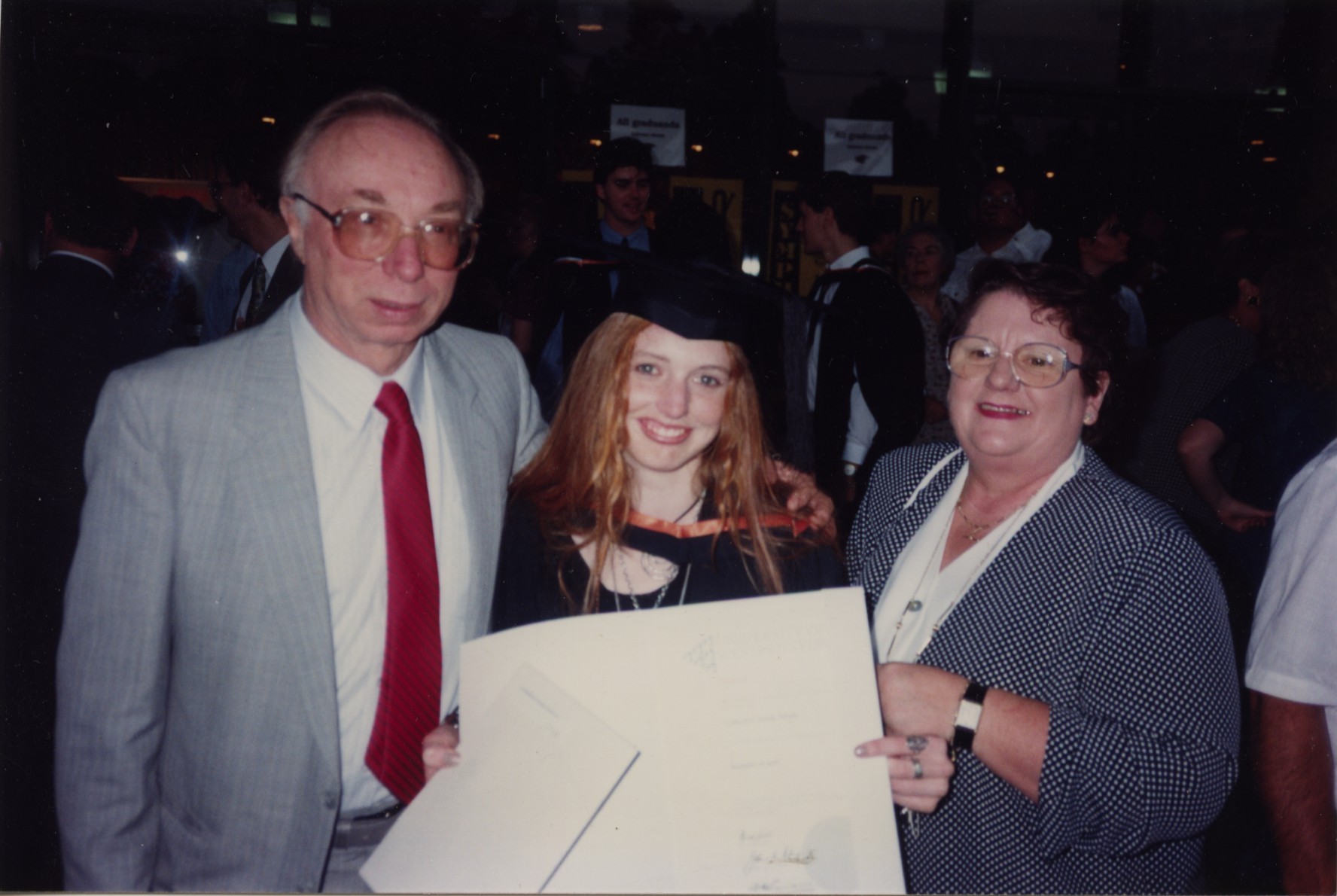

Riley, who is a graphic designer, always wondered where her creative streak came from as her adoptive parents did not have much time for art. But after having met her biological parents, she knew that she had chosen the right career path. Both her father and mother were technical drawers; her grandfather was an artist.

“Suddenly it was clear where my musical and artistic genes came from,” she says.

Complicated legal case

With her husband and children, Riley continues her journey to Courfaivre, the birthplace of her father. She is on a mission to find the house where he was born. But the family trudge through the snowy hamlet in vain.

Frozen to the bone, they get on the train to St. Ursanne before continuing their journey back to Basel.

They may not have found the house where her father was born, but Riley’s efforts to gain Swiss citizenship are gaining steam. Two days after their trip to canton Jura, Riley and her husband find themselves at a Zurich law firm.

It was at one of the many gatherings with her Swiss family that Riley’s cousin told her: “Your half-sisters, who are half Swiss, have a Swiss passport – you’re entitled to it too.” This revelation triggered something in Riley that has now preoccupied her for almost two decades.

Riley did some research on how to gain Swiss citizenship and contacted the Swiss consulate as well as local Swiss authorities. She was either referred to other places or turned away. “At first, I thought: ‘Okay, it may not be possible’,” she recalls. But over the years, she has felt a deep sense of injustice. “I am Swiss after all – my blood didn’t change when I was adopted.”

“Cate Riley’s case is complicated,” says Widmer. He believes that she has a chance to obtain the red passport, but cannot guarantee her any success.

A small window of hope

Under Swiss law, a child who is born abroad to a Swiss parent and who gains another nationality automatically loses Swiss citizenship at age 25 – unless the child has been registered with the Swiss authorities or has declared in writing that they wish to retain their Swiss nationality. The offspring of a person who loses their citizenship this way also lose their right to Swiss nationality.

One option for adoptees looking to gain Swiss citizenship is to annul their adoption. But this is out of the question for Riley, as it would be too painful for her adoptive family.

There may be yet another way for Riley to be granted citizenship. Within a year of finding out that her parents were Swiss, she had registered with the Swiss tourist office, which back then was affiliated with the Consulate. Under the old citizenship law, registration within a year was a requirement.

Riley is now hopeful. After years of research, she finally has a lawyer who can help her in her quest for getting Swiss citizenship – and for getting back a piece of her identity that she lost when she was adopted.

According to the Swiss NGO Pflege- und Adoptivkinder Schweiz, a counselling service for foster and adopted children, it became possible to legally obtain information about a person’s biological parents following the revision of the Swiss Civil Code in 2001. At the time, Switzerland was implementing the Hague Adoption Convention, so a new article was included in the civil code that entitles adult children to obtain personal details about their biological parents.

Adapted from German by Billi Bierling/gw

More

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.