Covid-19 vaccine: Why we still have a long wait ahead

Countries have started rolling out a Covid-19 vaccine, but it will likely take years to manufacture doses at the scale needed to reach the masses in Switzerland and much of the rest of the world.

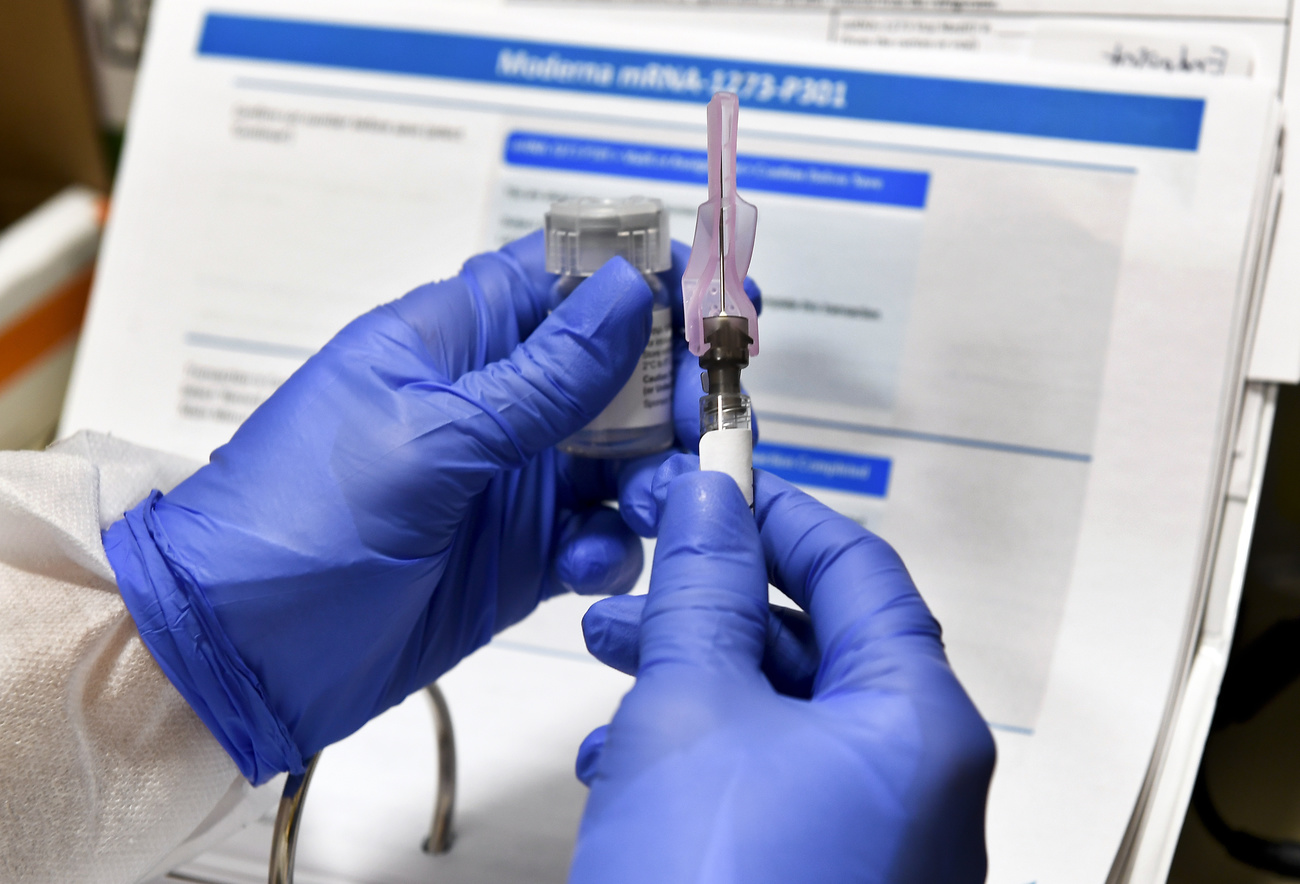

Light appeared at the end of the pandemic tunnel when a 90-year-old grandmother in the United Kingdom received the world’s first dose of Pfizer/BioNtech’s Covid-19 vaccine outside of a clinical trial, on December 8. The companies did in about 10 months what had never been done in fewer than four years.

Vaccinations in Switzerland are expected to start in January if the approval process goes according to plan for either the Moderna or Pfizer vaccines. However, making these vaccines available to the masses won’t happen right away.

The Swiss government estimates three-quarters of the population will be vaccinated by summer 2021. But a projection made by the London-based science analytics company Airfinity, at the request of SWI swissinfo.ch, predicts it could be spring 2022 before mass vaccination happens and vaccine-based herd immunity is reached in Switzerland.

More

Switzerland plans Covid-19 vaccination strategy

“Clinical trial results from Moderna and Pfizer/BioNTech exceeded expectations but we need to be realistic. There will be bumps along the road,” said Thomas Cueni, Director General of the International Federation of Pharmaceutical Manufacturers & Associations, at a media briefing last week.

“For the next few months life will remain difficult in most countries,” he added. Even if vaccines are approved by regulators in the coming months, producing and distributing them safely at scale will take much longer. Here are some reasons for this projected timeline.

There isn’t enough capacity to meet demand

Countries have shelled out billions of dollars to order more than 11 billion doses of vaccines – some of which may ultimately prove ineffective and be tossed aside.

The US has pre-ordered the most with 800 million doses secured and an option to add another 1.6 billion. The actual number of people this will cover is lower given that the two leading vaccine candidates require two doses.

The data estimates and projections in this story draw on various sources. One key source is Airfinity, which is a London-based private science information and analytics company founded in 2015. It provides real-time science intelligence to the healthcare industry, governments, as well as NGOs, academics and investors. Instead of relying on a single source, the company integrates all major data sources into one unified and comparable view. Airfinity’s Covid-19 data has been used by major media outlets like Nature, the New York Times, the BBC, and Bloomberg.

Airfinity’s vaccine-based immunity projections account for factors such as current supply deals, expected timeline for vaccine production, manufacturing locations, supply to each country, vaccine efficacy, as well as likely approval times. They don’t take into account natural immunity as a result of Covid-19 infection in the population.

Another key source for this article is the probability-based predictive tool developed by the Center for Global Development (CGDEV). The tool estimates it could take two years to produce enough vaccines to immunize 50% of the global, “low priority” population, and it could be mid-2023 before three-quarters of the population can be vaccinated on a global scale.

Switzerland has signed agreements with the makers of the three most advanced vaccine candidates (Pfizer, Moderna and AstraZeneca) to secure more than 15.8 million doses for a population of 8.5 million. It is also part of the COVAX Initiative – a global Covid-19 vaccine procurement and equitable distribution effort – that will provide doses for 20% of the Swiss population. On a per-capita basis, this puts Switzerland in the top ten countries in terms of vaccine procurement.

But because pre-orders have been made by a select number of largely wealthy countriesExternal link, they don’t reflect the actual worldwide demand of the more than 7.8 billion people on the planet.

According to the latest data by Airfinity, vaccine manufacturers have the capacity to make around 14 billion doses.

In September, Adar Poonawalla, chief executive of the Serum Institute of India, told the Financial TimesExternal link that pharmaceutical companies were not increasing production capacity quickly enough and that there won’t be enough for everyone in the world until 2024 at the earliest. The Institute is the largest vaccine manufacturer in the world, producing some 1.5 billion doses of various inoculations every year.

AstraZeneca, Pfizer and Moderna estimate that, among them, they can make 5.2 billion doses by the end of next year, which could cover the vaccination needs of around one-third of the world’s population. For some vaccines like AstraZeneca’s, the number of doses ordered outstrips the expected supply.

Most of these companies’ capacity is already secured in agreements and therefore won’t be distributed equally around the world. It is unclear how companies prioritise which countries receive ordered doses.

According to this data, vaccine candidates that have the most production capacity are not necessarily those closest to approval or fastest to produce. The most advanced vaccines such as the mRNA vaccines from Pfizer and Moderna use new techniques, which require building or upgrading factories and production lines.

A surveyExternal link of 100 manufacturers conducted in spring and published in June by the Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations (CEPI) found almost no MRNA vaccine manufacturing capacity in the world. This is why those vaccines are not expected to reach the masses quickly although they were the first out of the gate.

The Serum Institute in India has focused on more conventional viral vaccines and has saidExternal link it won’t be able to manufacture mRNA vaccines until next yearExternal link. It has already signed on to manufacture candidates from Astra Zeneca and Novovax, which explains these vaccines’ higher projected production levels. The Institute has also signed deals with COVAX to manufacture up to 200 million doses of Covid-19 vaccines for low- and middle-income countries, priced at a maximum of $3 per dose.

Moderna and BioNTech are leaning on large pharma companies to bring manufacturing muscle. Swiss-based Lonza has stepped in to build four production lines for the Moderna vaccine, three of which are located in Visp, in south-west Switzerland, with the other in the US. These four sites will produce enough vaccine for up to 400 million doses.

Lonza is producing the active ingredients, which is the most complicated part, but the vaccine will then be shipped to so-called “fill and finish partners” selected by Moderna. They include Catalent in the US and ROVI in Spain. It is unclear where the fill and finish capacity currently lies.

Airfinity told SWI swissinfo.ch that machines siphon fluid into millions of vials and syringes before each one is hand-checked for quality. Many plants today can fill and finish tens of thousands of vaccine doses per hour, but when the immediate need is for billions of doses, even the fastest robotic filling arm can be too slow to meet demand.

More

Emergency vaccine approval not legal option in Switzerland

Johnson & Johnson’s subsidiary Janssen Vaccines in Switzerland is also involved in the sterile filling and delivery of its vaccine for phase one and phase three trials. A company spokesman said that further clinical trials, planned as part of the broad approval process, will be supported by clinical trial samples from the company’s Bern site.

Building a new vaccine facility can take five to ten years and billions to get up and running.

Public health advocates have been calling on companies to support open licensing of their vaccine technologies in order to allow others, particularly in lower income countries, to produce the vaccines, and increase capacity.

Countries and companies are also hedging their bets across vaccine candidates because as the Center for Global Development points out, second-generation vaccines are often more effective than first-generation.

More

Why Swiss participation in WHO’s Covid-19 vaccine plan matters

“We need to be careful about committing all spare manufacturing capacity to the first candidates. While many vaccine factories are fungible, switching production between candidates can be slow and complex,” the Center writes in a reportExternal link.

Reinhard Glück, who worked in vaccine development for 30 years including at former Swiss vaccine firm Berna Biotech, told SWI swissinfo.ch that it is always true in the pharma sector that once a superior product comes on the market, the less effective version stops being used.

Vaccine production takes a long time

The production process itself also takes time. This varies by type of vaccine but can also depend on how fast authorities carry out safety checks, which by some estimates takes 70% of the manufacturing time.

It has been widely reported that it is faster and cheaper to make an mRNA vaccine than for adenovirus vectored DNA vaccine like Astra Zeneca’s and recombinant protein-based vaccines like that being developed by Sanofi/GSK. According to experts interviewed by swissinfo.ch, the latter can take six months to produce a batch.

The advanced mRNA vaccines are currently based on a two-dose regimen. In contrast, J&J told SWI swissinfo.ch that while its vaccine might be more complex to manufacture, its big advantage is that it is being tested as a single-dose regimen. The technology has already been used to develop vaccines against Ebola and Zika.

Switzerland is a major pharma and biotech hub, but very little vaccine research and production takes place in the country. This wasn’t always the case. In the 1990s, every few seconds someone received an injection of a vaccine from Berna Biotech. The company’s origins date back more than a hundred years to the Swiss Serum and Vaccination Institute.

In 2006, the Dutch company Crucell bought Berna Biotech, which was eventually bought by Johnson & Johnson (J&J). Part of the former site of Berna Biotech in Bern is used by J&J subsidiary Janssen to research its Covid-19 vaccine.

Vaccines are complex and not highly profitable business area, which is why companies such as Novartis have moved out of the vaccine business into more lucrative areas such as oncology.

Health experts in Switzerland have warned of vaccine supply bottlenecks because of the lack of production capacity. In an interviewExternal link on Swiss public television, SRF, health economist Tilman Slembeck from the Zurich University of Applied Sciences said, “It is a total illusion that in a crisis you can get everything from abroad. Every country looks to itself first when it comes to vaccines.”

Each production stage can demand up to 450 quality checks. Any potential problems with the formulation at any stage could result in the entire batch being discarded. According to the Swiss Therapeutics Law, all batches of vaccines marketed in Switzerland must be tested by an authorised laboratory before being released. Every monthExternal link, the regulatory body Swissmedic updates the list of approved batches.

The process is so meticulous that vaccines are usually only produced in a single factory, and each facility’s batch must be treated as a new product for the purposes of regulation. Philippe Paroz, a microbiologist who worked in vaccine safety including at Berna Biotech, compared the process to cooking. “If you are cooking mayonnaise at home, it’s not proven that the same recipe will work in your neighbour’s kitchen. The same is true for vaccines.”

Materials and technicians are in short supply

Bottlenecks can also happen at different stages. The Wall Street Journal recently reported that Pfizer slashed its production targets for its Covid-19 vaccine because of a lack of raw materials for its supply chain.

At a media briefing after these reports, Pfizer CEO Albert Bourla said that “If there were available more machinery, more technology and more raw materials, we wouldn’t make 1.3 billion, we’d make 2 or 3 billion. Right now, we are exhausting our capacity, and that of our suppliers after looking all over the world to find people who know what we are doing.”

More

Lonza ‘scaling up’ Moderna’s promising Covid-19 vaccine process

In an email, Lonza spokesperson Sanna Fowler told SWI swissinfo.ch that “potential bottlenecks on our side are sourcing equipment and raw materials as well as access to contractors and hiring and training new staff”. But she said that the company is on track to meet its goals and expects to start production in Visp before the end of the year.

Raw materials and equipment can mean anything from bio reactors and filtration and chromatography equipment to filling machines and glass vials. There is little data available on the global volume of such supplies; most glass vial production takes place in China.

Manufacturing manpower may also be a bottleneck; it can take more than 50 trained technicians to control quality when manufacturing biological vaccines, while only one is needed for medicines.

Distribution around the world is a logistics challenge

Once vaccines are ready, getting them to hospitals and doctors’ offices in countries with very different infrastructure and climate conditions poses a host of challenges.

MRNA vaccines are easier to develop and manufacture quickly but harder to deliver and administer because they need to be kept at very cold temperatures. The Pfizer vaccine needs to be kept at a temperature at or below –70 degrees Celsius. The World Health Organization estimates that up to half of vaccines are wasted every year, often because of inadequate temperature control in supply chains.

Swiss company Skycell has developed temperature-controlled logistics containers with monitoring devices to ensure the vaccines stay stable.

Companies say they have thermometers as well as sensor and tracking technology to make sure vaccines remain at stable temperatures. But the temperature issue still concerns Glück who is advising Spicona on its Covid-19 vaccine. “We need a vaccine which is stable, also in warm temperatures,” he says. “A vaccine that has to be kept at minus 20 degrees is not a vaccine that can reach everyone.”

Johnson & Johnson says it plans to use the same cold chain technologies it uses to transport treatments for cancer and immunological disorders.

More

Can Switzerland convince its people to take the Covid-19 vaccine?

And how will countries perform mass immunisation once the batches arrive? The Swiss government is setting up centres and aims to vaccinate 70,000 people per day, starting with high-risk groups. It also plans to make the vaccine free of charge.

Worldwide, some companies have said that they will charge different prices for the vaccine depending on a country’s GDP levels.

The WHO regional director for AfricaExternal link recently said that countries on that continent are far from being ready to vaccinate because they have not yet identified priority populations or set up tools for tracking and reporting results.

And since at least 60% of a population must take a vaccine to achieve mass immunity, some fear that vaccine skepticism that could thwart the rollout in some parts of the world.

There are still many open questions

The scale and speed of the vaccine rollout leaves many questions unanswered. Even if a vaccine passes the safety tests, experience with other new vaccines shows that more will come to light along the way about the vaccine’s effects on different demographic groups.

Some expertsExternal link have also criticised the design of the trials for not investigating whether the vaccines prevented severe Covid-19 illness and transmission of infection.

Companies and officials have given assurances that they haven’t cut any corners on safety, but there are no comprehensive, peer-reviewed studies available on the available Covid-19 vaccines. On December 1, Switzerland’s medical regulator Swissmedic said it lacked the necessary information to sign off on the three different coronavirus vaccines ordered by the government.

More

Switzerland secures three million doses of Pfizer/BioNTech vaccine

There are also questions about whether the vaccines will work in the face of virus mutations, as have been reported in parts of Europe. It also isn’t clear how long immunity lasts, and whether and when people might need a booster shot.

“There is a lot that could go wrong, and companies aren’t incentivised to talk about it,” said Anthony McDonnell, a policy analyst in the health team at the Centre for Global Development.

Glück also worries that so much has been invested in these vaccine candidates that they’ve become “too big to fail”.

“Taxpayers have invested so much, there is a sense that we have to keep going no matter what. That’s my fear.”

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

Join the conversation!