How photographing Montreux went from lax to exact

In over three decades of photographing the Montreux Jazz Festival, two Swiss photographers have amassed thousands of images of the world’s greatest musicians. But times and technology have drastically changed the job.

Miles Davis was sitting naked in his backstage dressing room at the Montreux Jazz Festival. At the same moment, freelance photographer Edouard Curchod walked past the half-open door. As the legendary trumpeter’s eyes met his, Curchod stammered an embarrassed apology.

To the photographer’s surprise, Davis, who was in Montreux for the fifth time, invited him in and asked: “What did you think of my concert?”

When Curchod replied that his English was not rich enough to express his emotion, Davis thanked him and invited him to take photos. Curchod captured the star from above the waist in that rare, intimate moment when he was unwinding alone.

It was 1988 and Curchod’s eighth year photographing the festival. In 1980, the photographer based in Vevey, near Montreux, had no accreditation for the event but knew the venue well. Every night, he entered the service door of Montreux Casino’s kitchen, then climbed through the serving-hatch into the concert hall.

Nobody asked any questions. There were no security staff in the hall and only two accredited photographers.

Curchod’s first festival photo, published by a Vevey newspaper that no longer exists, shows spectators at a concert by British band Q-Tips sitting on the floor. It was a rare sight in Switzerland at that time.

Like most of Curchod’s photos from the early 1980s, the image is black and white. “For colour photos, the lighting had to be good as the film wasn’t sensitive,” he explains. “Nobody asked for colour except a few magazines and record companies.”

He developed his photos in his car, took them to the newspaper to be re-photographed for printing and headed back for the next concert.

When Curchod was accredited in 1981, photographers had no time limits and could go backstage on the condition that they respected the artists.

The same year, photographer Philippe Dutoit covered James Brown’s concert for the Swiss magazine L’Illustré. Dutoit had just moved to Montreux and barely knew the festival. “I wasn’t even a great music fan,” he admits.

That changed two years later when he started photographing the entire event, working close enough to the artists to see them breathing.

By then, the swelling ranks of photographers could no longer go backstage without authorisation but could work throughout the concerts.

“The audience often sat on the floor and we moved around – we probably bothered them a lot,” says Dutoit. “That would be impossible now.”

Photos destined for next day publication had to arrive before the late-night printing deadlines. For Swiss media further afield than Vevey, they had to be developed, taken to Montreux station and left in the postal carriage of a train heading to the city where the publication was based.

The photos were in special envelopes that indicated they should not be put in postal bags. After depositing them, the photographers ran to a telephone box, called the person tasked with picking them up and told them when the train was arriving.

Changing artists

Until the early 1990s, there was a strong demand from foreign media for photos of artists performing at Montreux. Music festivals were far fewer and the event was not just another date on artists’ international tour calendars.

“They stayed for two or three days, sometimes a week,” Dutoit says. “Dizzy Gillespie used to play tennis by the lake. Nowadays, they arrive in the afternoon and the next day they’re in London or Berlin.”

One of Dutoit’s most gratifying – and nerve-wracking – moments occurred backstage in 1985 when he showed Miles Davis his photos from the previous year.

“He was scary,” says Dutoit. He remembers trembling as Davis looked from each photo to him and asked why he had taken it. After a few uncomfortable minutes, Davis gave him an approving slap on the shoulder. “It was extraordinary,” says Dutoit with emotion.

The festival moved in 1993 to Montreux’s newly enlarged congress centre. The ticketed concerts took place in the Stravinsky Hall and the New Q’s hall – a short-lived nod to Quincy Jones who was co-producing the event with its founder and director Claude Nobs for the third and last time. The addition of stands lining the lakeside and a free open-air stage attracted a record number of 120,000 festival-goers the following year.

By then, photographers were only allowed to work during the first three songs of most concerts and had to choose between the halls.

“We always hoped one concert would start late but a lot of the time, they were both late and we never really knew where to go,” remembers Curchod.

No more film

By 2000, the digital camera revolution had begun. Dutoit remembers spending CHF30,000 on a Nikon-Kodak DCS 760, which he used for less than two years.

Curchod wasn’t convinced of the merits of digital until the arrival of the Nikon D1H in 2001. Technology evolved so quickly that in 2003, his sole concern was that the quality would “kill the atmosphere of the images”.

“We were used to having ‘noise’ in our photos and now we had cameras with sensors that were better than film. It felt like we were working in daylight,” he explains.

But Curchod soon realised that digital cameras allowed the festival photographers to worry less about technical aspects and concentrate more on capturing the atmosphere through the expressions of the musicians.

“We started taking colour close-ups,” says Curchod. “Previously, the longer the telephoto lens was, the faster we had to work before the subject – or we – moved. We preferred not to take risks with the quality and took wide shots showing the stage with a couple of musicians.”

In more than three decades, the photographers have experienced some unpleasant moments and frustrations. Dutoit has been kicked by an artist’s bodyguard and had a camera broken during a scuffle with a security man. Curchod wryly recounts how increased restrictions and growing numbers of photographers prompted him to vow that the 25th festival would be his last.

Twenty-four years on, the event counts three main ticketed venues and eight free stages. Antoine Bal, head of PR for the festival, says the number of photographers accredited “varies enormously” but, generally, ten work in the Stravinsky Hall and Montreux Jazz Lab and no more than three in the Montreux Jazz Club. A list of photographers is submitted to the artist’s management, who decide.

“Sometimes, there is only one photographer,” says Bal, adding: “Image control is important now.”

Yet Curchod and Dutoit agree that the positives outweigh the negatives and both still feel excitement when they are immersed in the atmosphere.

“I am privileged to see artists come off stage and fall into each other’s arms because they’ve shared the joy of performing,” Curchod says.

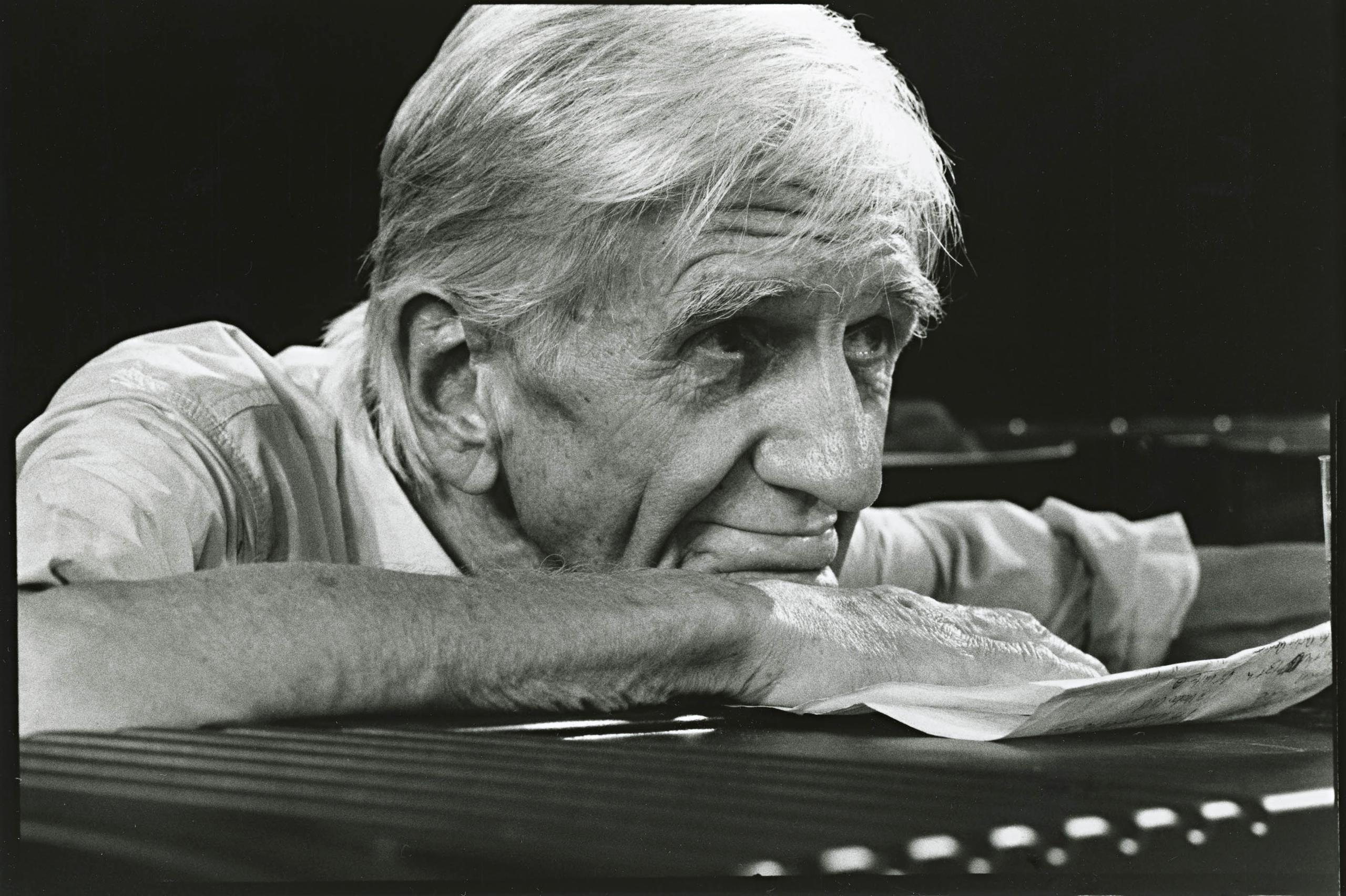

A photo of Gil Evans’ last concert at Montreux in 1986 is one of his favourites. Evans was performing with a group of young musicians. At one point, he stopped, leaned across his keyboard and watched them. Curchod’s image conveys the old musician’s pleasure in seeing the new generation take over. He died in 1988.

“When I took the photo, I had goose bumps,” says Curchod. “When I look at it now, I feel the same.”

Curchod, 64, has some 800,000 photos of the festival and is not ready to stop. But Dutoit, 66, will photograph Montreux for the last time this summer. He plans to publish a book of his work for the 50th anniversary in 2016 and has already chosen the cover: it is a striking detail of Miles Davis’ fingers on his trumpet, a tribute to a legend who gave Montreux – and the photographers – some outstanding moments.

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.