Swisscoy: How Swiss participation in Kosovo peace mission lays bare the neutrality debate

The Swiss Armed Forces take part in the NATO-led international peacekeeping force in Kosovo. This Swisscoy mission is key to understanding the neutrality debate in Switzerland – and what role NATO plays in it.

Few countries are more significant for Swiss neutrality than Kosovo. The controversy over whether Switzerland was jeopardising its neutrality in Kosovo began ten years before Europe’s youngest state declared its independence.

The Alpine nation began its military presence in Kosovo in 1999, just a few months after the end of the war. Since then the Swiss Company unit of the Armed Forces (Swisscoy) has been taking part in the international KFOR mission, tasked with securing peace in the region. Switzerland has therefore been integrated in NATO structures for almost a quarter of a century.

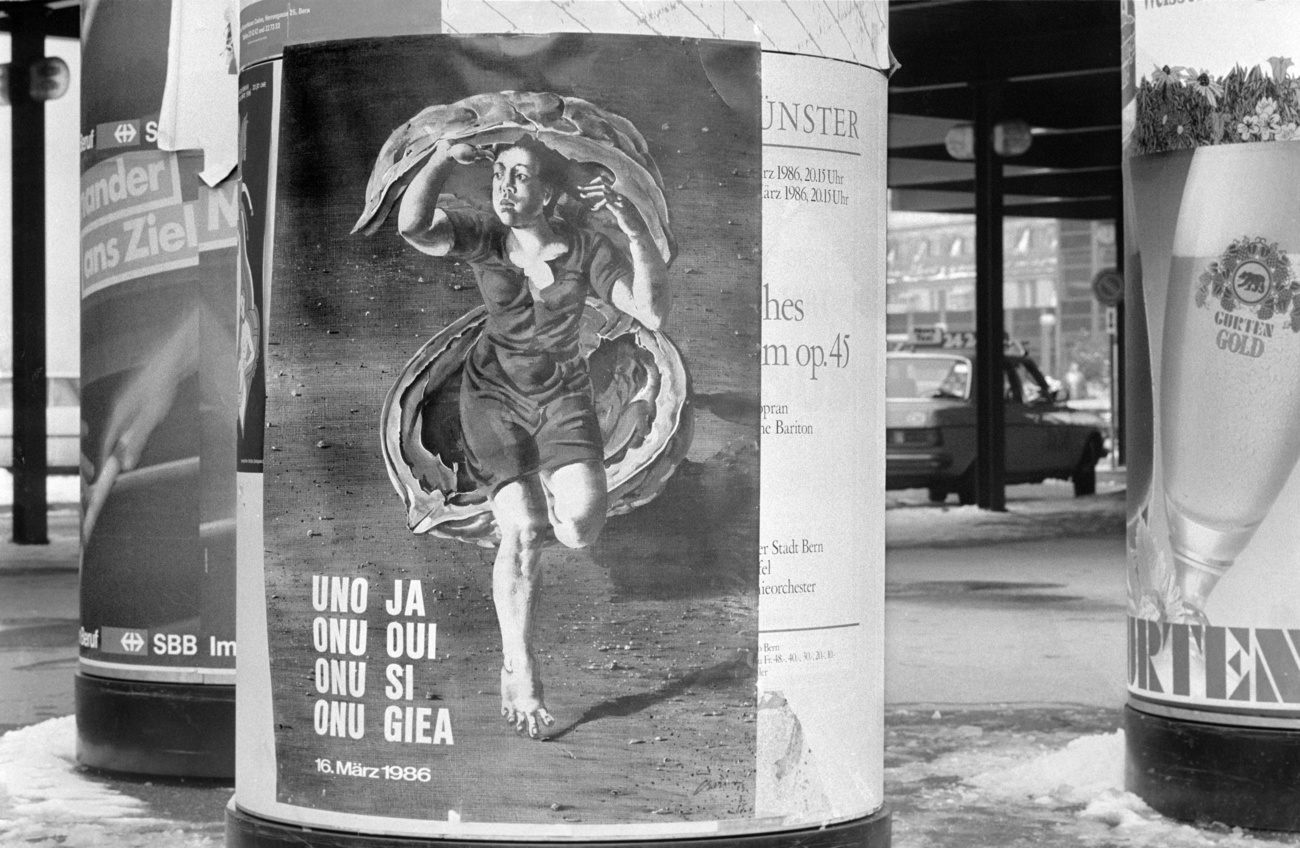

The KFOR mission was established by the so-called Kosovo ResolutionExternal link of the United Nations, which means that it is covered by international law and therefore complies with the Swiss law on neutrality. However, the mission was criticised by some in political circles at home: the left denounced the militarisation of Swiss foreign policy, while the right claimed it undermined neutrality.

“In Switzerland, it is striking that foreign military missions were always discussed under the auspices of neutrality. This was much less the case in other neutral states,” says Michael M. Olsansky, a military historian and lecturer at the Military Academy of the federal technology institute ETH Zurich. Sweden and Ireland, for example, have also provided troops for peace missions since the 1950s, and Austria is a mainstay of the KFOR, Olsansky points out.

Isolationism versus openness

After the end of the Cold War, Switzerland began to rethink its security policy. Milestones were the 1993 Neutrality ReportExternal link, which aimed to move away from an overly rigid neutrality, and the 1999 report Security through CooperationExternal link, which deepened multilateral cooperation, including with NATO. When the Federal Constitution was completely renewed in 1999, Switzerland defined peacebuilding as a mandate of the army, alongside national defence and support for civilian authorities.

According to Olsansky, Swiss peacekeeping missions lay bare the political debates surrounding the opposing currents of isolationism and openness.

In debates on international cooperation, conservatives and isolationists, in particular, always emphasise neutrality. “However, this is not a debate about neutrality, but purely about neutrality policy,” says the military historian.

For Olsansky, the case of Kosovo shows the tensions that neutrality has to endure. The Swisscoy mission, which once caused so much controversy, was actually unproblematic in terms of neutrality.

The step towards recognising the state was much more daring. “In this case, Switzerland explicitly positioned itself in a foreign policy conflict and took a clear stance in favour of one party to the conflict, as it was one of the first states to recognise Kosovo in 2008.”

‘The army’s role is national defence’

The loudest criticism of the Swisscoy mission comes from Pro Switzerland, an organisation in favour of neutrality and national defence that flat-out rejects Swiss participation in the KFOR. Stationing troops abroad is not compatible with the country’s neutrality, says Stephan Rietiker, its president.

“The task of the army is to ensure national defence – not to participate in dubious missions elsewhere,” he says.

Pro Switzerland, which is closely connected to the right-wing conservative Swiss People’s Party, is considered isolationist and decidedly critical of the European Union and NATO.

Rietiker rejects the arguments put forward by those in favour of the Swisscoy mission – peacebuilding, security, curbing migration and solidarity. “NATO is a warring party and working with it certainly doesn’t promote peace,” he says.

In Rietiker’s opinion, Swiss troops are only responsible for secondary tasks in Kosovo and would have to request military protection from the KFOR in an emergency. “This is of no use to anyone and is purely a PR exercise. We should cancel it as soon as possible,” he says.

The oldest Swiss deployment abroad is on the Korean peninsula, with members of the Armed Forces stationed in Panmunjom since 1953 as part of an international peacekeeping mission. The mission is set to continue until North and South Korea conclude a peace agreement. Before then, Switzerland cannot relinquish its mandate.

In 1988, the Swiss government decided to expand Switzerland’s involvement in United Nations peacekeeping missions. In the decades since, nearly 14,000 members of the Armed Forces have been deployed in military peacekeeping missions. There are currently around 280 members of the Swiss Army deployed in 14 missions in a total of 18 countries.

In Switzerland, Rietiker adds, border protection is not guaranteed and the army is understaffed, so one cannot withdraw military personnel and talk about security. The argument that migration would be curbed by the mission in Kosovo is a real fabrication: “Our borders in the south are wide open, while our neighbours are sealing themselves off,” he says.

The Pro Switzerland president agrees with the idea of solidarity – but, he says, “we must show solidarity with the global community and not unilaterally with a group of countries. That means offering our services to everyone and providing humanitarian aid in an emergency”. On this single point, loose and informal cooperation with NATO is conceivable, he adds.

Switzerland is heading in the wrong direction, says Rietiker: “The creeping rapprochement with the EU and NATO is obvious. And it is also obvious that this is undermining Switzerland’s neutrality.” He believes, however, that this ultimately benefits Pro Switzerland and its political projects. Rietiker points to the People’s Party’s neutrality initiative, aimed at preventing Switzerland from joining military alliances or imposing sanctions. The initiative, Rietiker says, has received a lot of support because the population sees in which direction the so-called pro-EU and NATO “establishment” is pushing.

‘Minimal contribution to solidarity’

Others see things differently. Military expert and journalist Georg Häsler explains it this way: the Swiss contribution in Kosovo was a deliberate contribution to the European security order from the very beginning and the importance of the Swiss military mission increased significantly with the large-scale Russian invasion of Ukraine.

“The strict interpretation of Swiss neutrality – take the example of the ban on the transfer of defence equipment – was a source of irritation for many in Europe,” says Häsler. “The Swisscoy mission is a kind of minimal contribution to solidarity with our European allies”.

This was also explicitly formulated this year during the parliamentary debates on the renewal of the Swisscoy mandate: “With Swisscoy, Switzerland is making a solidarity-based contribution to Europe’s security. This is […] particularly important because to some extent our hands are tied in the war in Ukraine.” Cancelling the mission would be seen internationally as an affront.

According to Häsler, the mission also serves as a connector. “Swiss military personnel work closely with NATO troops,” he says. “This creates connections and contributes to mutual operational understanding – how structures work, how decisions are made, and how orders are carried out”. Furthermore, although Switzerland’s accession to NATO is not up for discussion, the Russian invasion has brought Switzerland closer to NATO. “The voices in favour of a more intensive exchange with NATO are getting louder,” says Häsler.

Other countries that are part of the KFOR mission also face difficult political choices that sometimes lead to odd results. For example, Greece and Romania, two EU states that do not recognise Kosovo as a country, have a military presence there.

KFOR is expanding – and Swisscoy stays

The tensions between Serbia and Kosovo are not easing and KFOR is currently being expanded. The message is clear: the forces are here to stay. The 195 Swiss soldiers continue to patrol and fulfill their important role as logistics and engineer troops within KFOR. The Federal Council has also decided to increase the contingent by 20 members of the armed forces as of April 2024.

For Switzerland, a stable Balkan region is important not only from a geopolitical perspective, but also because of the large former Yugoslavian diaspora communities living in Switzerland. Swisscoy shows that military missions abroad can be a good launching pad for keeping issues surrounding Swiss neutrality high on the political agenda.

Since 2022 Switzerland’s rapprochement with NATO has once again been the subject of controversial debate at a political level. However, in practical terms this was already evident in the Swisscoy mission in 2019. During that year Switzerland deployed a deputy KFOR commander for the first time. In this position, he commanded NATO troops.

Edited by Benjamin von Wyl/Translated from German/gw

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.