Is housing asylum seekers in underground shelters inhumane?

The Swiss parliament recently rejected a credit request to build containers that would accommodate asylum seekers. Lawmakers argued that the many underused civil defence bunkers in the country could easily do the job.

There is plenty of room in civil protection shelters, so no need to spend CHF132.9 million ($148 million) on containers: this was the message delivered in June by the parliament in Bern, which turned down a plan to create temporary accommodation inside containers for up to 3,000 asylum seekers.

The proposal, put forward by Justice Minister Elisabeth Baume-Schneider of the Social Democrats and backed by Finance Minister Karin Keller-Sutter of the centre-right Radical-Liberals, was rejected by the right-wing parties. Some lawmakers from the Centre and the Radical-Liberals did not want to give fuel to the conservative-right Swiss People’s Party in the middle of an election year.

Baume-Schneider’s goal was, however, commendable: to prepare for a massive influx of asylum seekers this year by organising adequate accommodation for them in containers. As the federal government is responsible for the initial reception of people seeking asylum (the cantons are then in charge of managing and housing the quota of migrants assigned to them,) she had proposed various sites on army land, mainly in cantons Vaud, Valais and Jura.

The argument that sparked the rift

The Senate, however, rejected the requested credit – even if was divided in half, as suggested by the committee dealing with the plan. The House of Representatives tried in vain to get this solution – to release CHF66.45 million for the containers – through in the chamber.

Many parliamentarians called into question the actual urgency of the situation. They also criticised the lack of precise data from the State Secretariat for Migration (SEM), which was unable to say exactly how many places were available in the civil-defence shelters.

It was precisely this issue that sparked the rift: the capacity available inside the shelters. Parliamentarian Benedikt Würth of the Centre Party argued that these public facilities, which cost the Swiss state millions of francs, would fit the bill perfectly.

The cantons countered that they wanted to keep the shelters in reserve to house the asylum seekers in their care – an argument that fell on deaf ears.

Disappointed by the outcome, Isabelle Moret, a senator from canton Vaud in charge of migration policy, told Swiss public radio RTS: “We have decided in Vaud not to put families with children in civil protection shelters, as they are not suitable for children.”

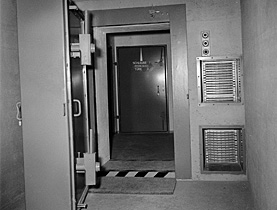

As well as being underground, the bunkers are sometimes found under schools and can only be used at night. “This is no dignified way to host families in our country,” she said.

A stay as long as 13-14 months

Mohammad Jadallah, a Sudanese refugee, has first-hand experience of the underground shelters. Reopening them to house migrants today is a step backwards, he told SWI swissinfo.ch. Jadallah was a driving force behind the Stop Bunker movement, which caused a stir in the mid-2000s by denouncing the use of bunkers for asylum seekers.

“The shelters were built for emergencies, as a place to live for two to three weeks at most,” he said. “In Geneva, I spoke with refugees who had been staying in shelters for 13 or 14 months. That was tough. Apart from the problems that arise from living together in close quarters (fights frequently broke out), there were also health issues, like bedbugs. If the goal is to help these people integrate into society, then housing them in shelters makes no sense.”

“Those living there are already traumatised by war,” Jadallah added. “We should not think that everyone who comes here does so for economic reasons. War is everywhere in the world.”

Thanks to the Stop Bunker campaign, led by asylum seekers and half a dozen associations, the Geneva authorities stopped using shelters to house migrants, at the time mainly from Syria, in 2015. But last autumn their doors were reopened. “Not to house Ukrainians, but Afghans [and] Iraqis,” said Jadallah.

Iskander Guetta, the co-curator of an exhibition on underground shelters held this spring in Lausanne, is indignant: “We definitely support opening these spaces to the public. But not to house migrants. Some of those living there have told us how upsetting they find it to be holed up underground, hidden from view. These are dark spaces that just exacerbate all the suffering they have gone through since leaving their homes.”

More

Switzerland sets ‘gold standard’ for designing bunkers

Only an emergency measure

Housing people in civil defence shelters “should remain a temporary emergency measure of last resort,” said Swiss Refugee Council spokesperson, Lionel Walter. “As far as possible, facilities of this type should not be used to maximum capacity. The refugees’ freedom of movement must in no way be restricted, and they must be able to go outdoors at all times. Families, children and vulnerable people should not be accommodated there.”

According to Samuel Wyss, a spokesperson at the SEM, his department has been providing different kinds of accommodation for decades, including some civil-defence shelters, which are in principle only resorted to when no other option is available. It then falls to the cantons, however, to apply the different measures foreseen, according to the migrant quotas assigned to them and the number of housing spaces available.

It’s difficult to know just how many refugees have stayed in civil defence shelters over the years. But the practice is ongoing. In mid-June, 520 of the 5,480 people currently housed in SEM facilities were in underground shelters. “As far as possible, the people placed in underground facilities are the ones who get a decision [on their application] quickly,” said Wyss.

People who have fled Ukraine since Russia’s invasion began in February 2022 have been given temporary accommodation in such shelters, even though the premises bring back difficult memories of the war. But this is also the case for most asylum seekers, as Jadallah of Stop Bunker pointed out.

In 2013, the Federal Court ruled that the living conditions in underground shelters were not so inhumane.

“Civil protection facilities were clearly designed as emergency shelters which, although habitable, are not intended as long-term housing solutions,” the Court wrote. “However, having to stay there as an emergency-aid measure, which is in principle temporary, without being obliged to spend all or part of the day there (for which purpose reception centres are available), cannot be considered to constitute inhumane or degrading treatment for a person who is not particularly vulnerable.”

Edited by Samuel Jaberg. Translated from French by Julia Bassam.

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.