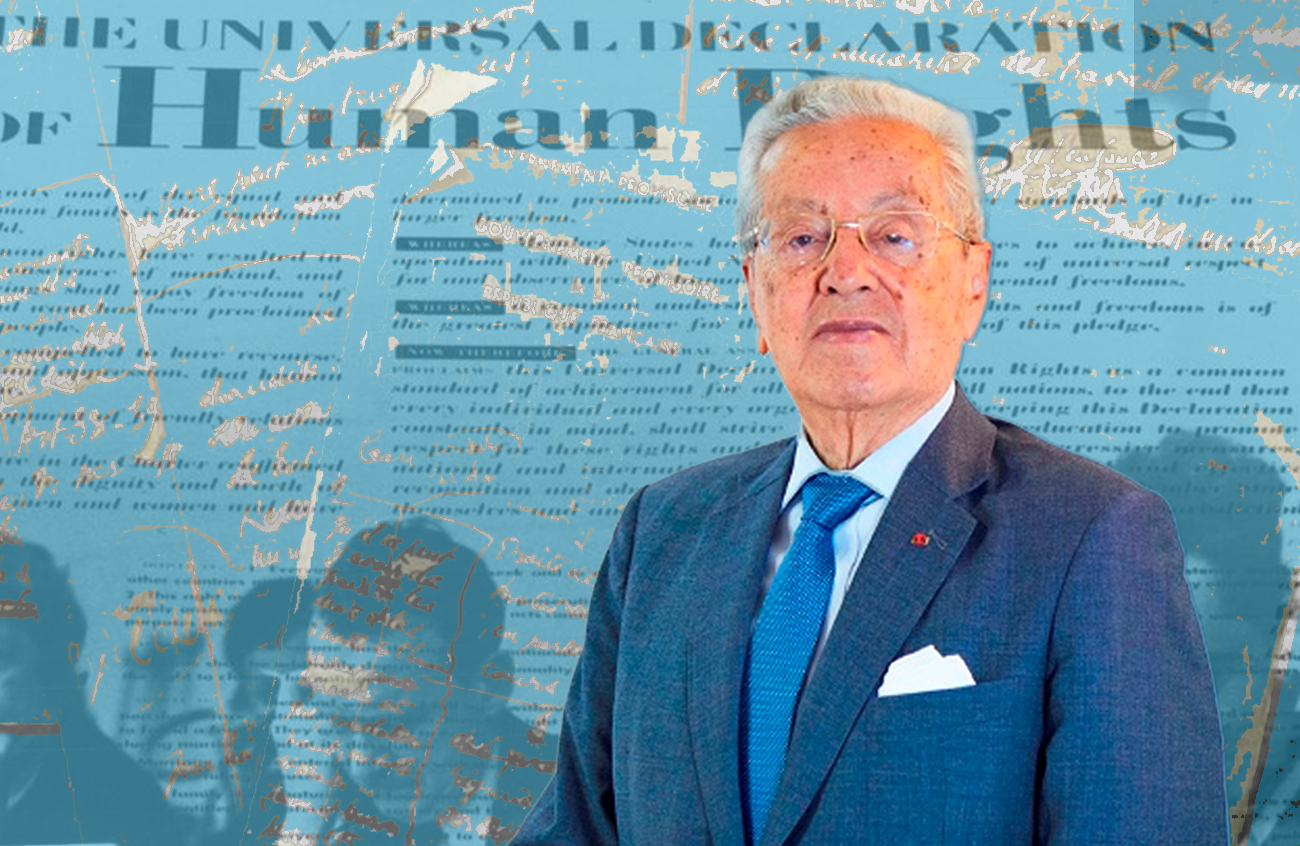

José Ayala Lasso: ‘We should not lose our faith’

It’s almost 40 years since he took office, but José Ayala Lasso, the first United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights, has not lost faith in humanity.

Nowadays, the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights is one of the most well-known UN agencies. It has multiple committees (on racial discrimination, on the rights of the child, on the prevention of torture, for example), and dozens of special rapporteurs, whose job it is to examine every aspect of the human rights records of member states. But it didn’t start like that. In 1948, when the Universal Declaration of Human Rights was created, there was no UN Human Rights Commissioner, no UN Human Rights Council, and no special rapporteurs. When I interviewed him, Jose Ayala Lasso pointed out that the Cold War, and different interpretations of what the declaration actually required of member states, stood in the way.

Throughout 2023, SWI swissinfo.ch has been marking the 75th anniversary of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, a ground-breaking set of principles and also – fun fact – the most translated document in the world. The current UN High Commissioner for Human Rights, Volker Türk, describes the declaration as “a transformative document… in response to cataclysmic events during the Second World War.”

The very first UN commissioner, Jose Ayala Lasso from Ecuador, took office in 1994. Why did it take so long to appoint someone when the Universal Declaration was drafted in 1948?

Our Inside Geneva podcast has interviewed all the former UN High Commissioners for Human Rights (a job sometimes called the UN’s toughest) to hear their experiences, their successes, and their challenges.

That stalemate continued for nearly 50 years, during which the UN’s human rights work was confined to a small, low-key office in New York. But when the Cold War ended in 1989, there was a rush of multilateral optimism such as the United Nations Conference on Environment and Development (UNCED), also known as the Earth Summit, in Rio in 1992 and Copenhagen’s World Summit for Social Development in 1994. For a few brief years, the world united around some big goals, among them the World Conference on Human Rights in Vienna in 1993.

Lasso, now 91, was representing Ecuador at the UN. He was deep in negotiations for reform of the UN Security Council, and wasn’t especially interested in switching to negotiations over the UN’s human rights work.

But the more he thought about it, the more he felt it was time to put the Universal Declaration at the centre of the UN’s work, with a UN human rights commissioner in charge of a Geneva-based team to uphold the principles of the declaration – principles Lasso believed should be obligatory.

“Some [UN member states] thought it was a declaration, not a compulsory and obligatory law,” he told the Inside Geneva podcast. “Others thought the principles in the declaration were so important that they should be applied as a law. I tried to support this second position.”

More

Inside Geneva: universal human rights at 75. Who defends them?

When agreement was reached to create the role of UN High Commissioner for Human Rights, then UN Secretary General Boutros Boutros-Ghali rewarded Lasso for his hard work by appointing him to be the first in the job. He took office in April 1994, just as the Rwandan genocide was beginning.

“I had to go there,” he said. But by the time Lasso got to Rwanda, it was already May, and the Tutsi leader Paul Kagame complained bitterly that the genocide inflicted on his people was “near to completion”. Nevertheless, the brand new UN human rights commissioner felt he “had to do something… the only action I considered useful at that point was to talk with the government, the Hutus, and the Tutsis.”

His strategy came too late, and did not achieve much, but in fact the UN had already failed in Rwanda before Ayala Lasso even arrived in Geneva to an office that had “not a dollar” of budget and just two staff.

Dialogue or confrontation?

His memories of Rwanda and attempts to talk to people committing the most horrific human rights violations are a thread running through all our interviews with former UN human rights commissioners.

What is the best way to confront atrocities? Dialogue or confrontation? Different commissioners have taken different approaches. Lasso believes both are necessary.

“If you see human rights through the lens of communism, probably you see them in a different manner when you see them through the eyes of democratic governments. I do not think that we should accept violations. But we should try to understand the reasons of the other: why {does} the regime, the totalitarian regime act in a certain way? Why?”

“The basic principle is the human being. Human beings are to be respected. They are equal in dignity and in rights, as the declaration says. We should believe, we should not lose our faith in the capacity of human beings to act correctly.”

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.