Magnitsky Affair: Switzerland to return suspect millions to Russia

Switzerland is to return money confiscated from three Russian citizens accused of being involved in one of the most notorious cases of fraud in recent times.

The assets are being unfrozen under the terms of a recent decision by the Federal Criminal Court. This comes against a backdrop of severe tension between the West and Moscow and risks tarnishing the image of Swiss justice internationally.

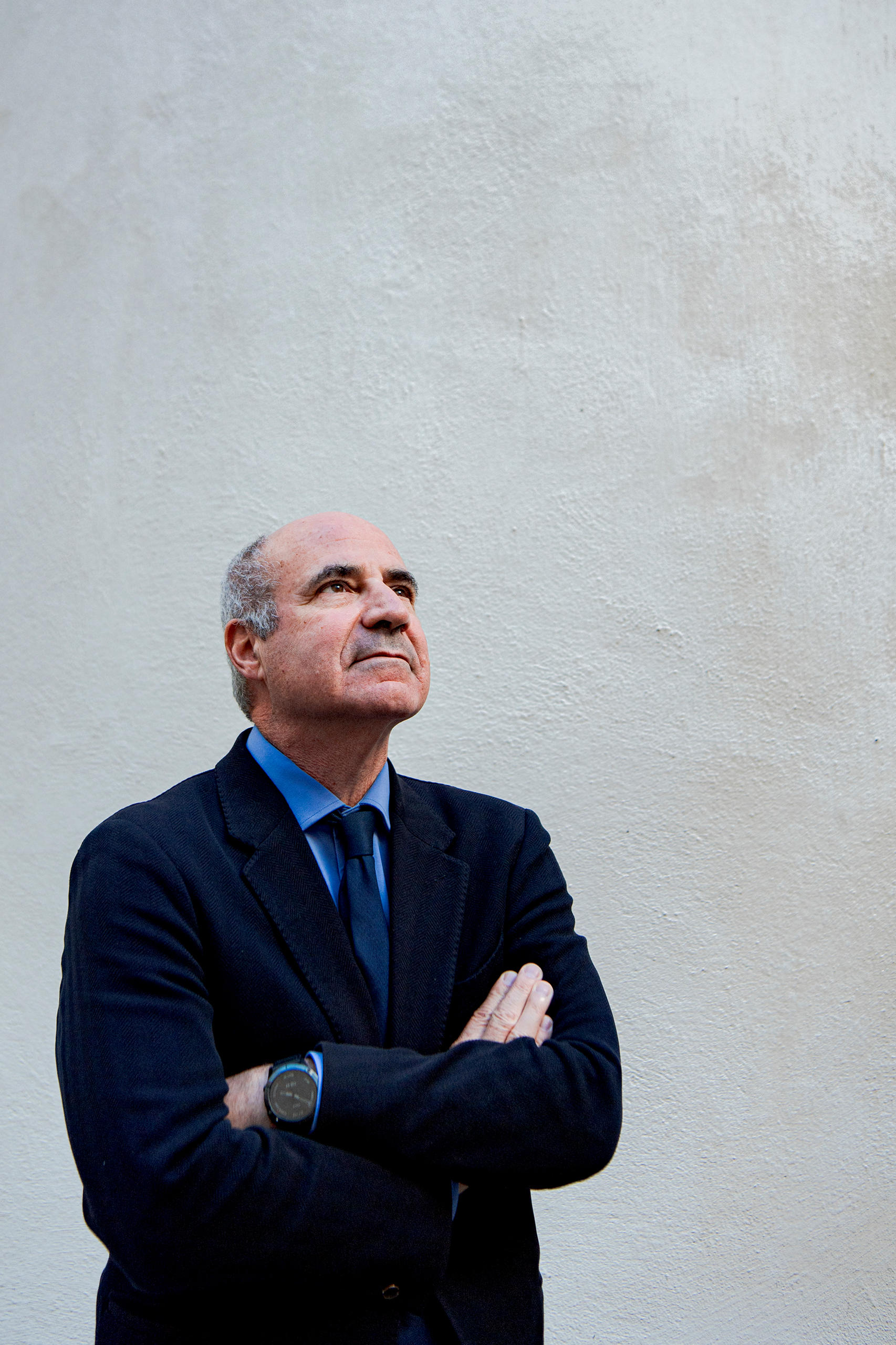

“It seems that the Swiss justice system is incapable of dealing with money laundering,” said Bill Browder, an American financier and now a British citizen who is the founder and CEO of Hermitage Capital Management. This is his take on the recent decision by Switzerland to hand back CHF14 million ($15.3 million) to three Russians sanctioned in the US and other Western countries: Vladlen Stepanov, Denis Katsyv and Dmitry Klyuev.

The three are leading figures in what has become known as the Magnitsky Affair, named after the Russian lawyer Sergei Magnitsky, who died in custody in suspicious circumstances in 2009 after having exposed a huge financial fraud. Hermitage believes itself to be the main victim of the fraud, and prompted a criminal investigation in Switzerland, the country where a part of the money was stashed away.

“We initiated the case, and provided full proof of the fraud against us. Yet the Swiss authorities have decided to release the money,” Browder says. In an interview with SWI swissinfo.ch, he expressed his strong disapproval of the court’s decision to free up the money for reimbursement to those whom he considers “Russian criminals”.

The affair started in 2007 when Russian police raided the Moscow offices of Hermitage Fund, at the time one of the biggest foreign investment funds active in Russia. Shortly afterwards, a group of Russian citizens – which the US Justice Department terms a “criminal organisation” – made a request to the Russian Treasury to refund to them the taxes paid by three Russian subsidiaries of Hermitage.

These companies had meanwhile changed ownership, through falsification of documentsExternal link. The tax refund was claimed because of debts these companies supposedly owed. It was granted by the Russian government. The amount of the refund was thought to be about $230 million (CHF211 million). The money ended up in the pockets of the various people who had been involved in the fraud. This money was then dispersed all around Europe, Switzerland included, through a network of shell companies and numbered accounts.

Millions frozen

In March 2011, following the filing of a complaint by Hermitage, the Office of the Attorney General (OAG) in Switzerland started a criminal investigation. This identified about 50 suspect accounts, and CHF18 million was frozen in Swiss banks. Almost half this money belonged to Vladlen Stepanov, a businessman and – significantly – the husband of Olga Stepanova, a senior tax official in Moscow whose signature had authorised the fraudulent transfers.

The rest of the confiscated money belonged to two other people involved in the affair, Dmitry Klyuev and Denis Katsyv. Klyuev, a former owner of the Russian bank from which most of the money originated, is regarded as one of the brains behind the operation. Katsyv, a son of the former vice-president of the Moscow regional government, is the head of Prevezon Holdings, a Cypriot company which was finedExternal link $6 million in a plea-bargaining deal in the US for receiving proceeds of the fraud. Defending the legal interests of Prevezon Holdings in New York was Russian lawyer Natalia Veselnitskaya. She had been in the news in 2016 after meeting the son of then presidential candidate Donald Trump.

Katsyv is not currently subject to sanctions, but the Stepanovs and Klyuev have been sanctioned in the USExternal link, in BritainExternal link, in Canada and in Australia for their role in the fraud.

Established link

On July 21, 2021, federal prosecutor Diane Kohler signed a document to drop the charges and close the case.

“The investigation has not revealed any evidence that would justify charges being bought against anyone in Switzerland,” the OAG said in a statementExternal link. It added, however, that “a link has been established between some of the assets under seizure in Switzerland and the predicate offence committed in Russia”. The “some”, in this case, is about CHF4 million out of CHF8 million deposited to a Credit Suisse account that was opened by the offshore company Faradine Systems Ltd, controlled by Stepanov, as reported by Swiss media Gotham City.

More

Switzerland drops Russia graft probe triggered by Magnitsky case

In the decision to drop the case – which SWI swissinfo.ch was able to review in full – the roundabout route of the money from three subsidiaries of Hermitage belonging to Browder to Switzerland was traced. From Russia, it passed through Latvia, ending up in Zurich, where, mixed with other funds, it went through four Credit Suisse accounts. Apart from the CHF4 million confiscated, sums under CHF100,000 were confiscated from the UBS accounts of Prevezon Holdings and two other companies controlled by Katsyv.

No guilty party

The Swiss investigation encountered several practices typical of money laundering: the use of transit accounts, the speed and sheer volume of transfers, and the frequent mixing of assets through shell companies in several countries. Such opaque practices “were to prevent the discovery of the criminal origin of these funds”, according to the OAG statement. However, for the OAG, the investigation did not produce enough evidence to charge anyone in Switzerland.

The only person the prosecutors found was under “definite suspicion” of money laundering had died in mysterious circumstances. Alexander Perepilichny was a financial operator who had been in on the fraud, having transferred several million to the accounts opened by Stepanov in Zurich. Perepilichny had later changed sides and sought refuge in the UK, where he provided information to Browder. In fact, he gave him the documents on which Browder based his later lawsuit.

In November 2012, shortly prior to a face-to-face meeting with Stepanov arranged by the federal investigators, Perepilichny died while out jogging in a London park. Two years after his death, a life insurance company with a policy on Perepilichny ordered tests which revealed poisoning by the toxin Gelsemium elegans, called “heartbreak grass” because its leaves, when ingested, cause heart failure.

CHF14 million to be handed over

After a ten-year investigation, apart from the confiscated CHF4 million the Swiss officials were unable to demonstrate a direct link between most of the money frozen in Switzerland and the fraud in Russia. Accordingly the OAG decided to allow the money to be refunded to its owners. Stepanov will get 55% of his frozen deposits ($5.5 million), Klyuev will get 100% of his ($38,000), and Katsyv will get 99% of his ($8 million).

This decision is highly controversial and raises several questions. For one thing, what criteria did Switzerland use in deciding how much money should be confiscated and how much released? What can be done if, as in this case, the proceeds of fraud passed through several accounts, where they were mixed with other funds of uncertain origin?

At the international level, the Palermo ConventionExternal link, ratified by Switzerland in 2006, states that “if proceeds of crime have been intermingled with property acquired from legitimate sources, such property shall, without prejudice to any powers relating to freezing or seizure, be liable to confiscation up to the assessed value of the intermingled proceeds”. The federal prosecutors, however, opted for the “method of proportional calculation”, a solution which for the officials has “the advantage of favouring neither party involved”.

This approach has been criticised by Mark Pieth, professor of criminal law at the University of Basel, according to whom “this method tends to favour money launderers, who can rely on structures able to launder their ill-gotten gains dozens of times if need be”.

Hermitage excluded

The same day the investigation was closed, the OAG decided to exclude Hermitage from being a party to the case because it did not consider the British-based fund a victim of the fraud that happened in Russia.

During the investigation, Browder was unsparing with criticism of the modus operandi of the Swiss investigators, accusing them of slowness, reluctance to act, and even corruption with the Russian authorities.

The corruption accusation refers to the case of a federal police detective, used by the OAG for investigations involving Russia, who was fired and later convicted of corruptionExternal link for accepting an invitation from the deputy prosecutor-general of Russia to a bear-hunting trip in Siberia. As emerged during the court case against him, during his time there, the officer discussed the Magnitsky case and how to stall the Swiss investigation, in particular by discrediting the work of former parliamentarian Andreas Gross, who had written a report on the matter for the Council of Europe.

And there was more. The police investigator met the lawyer acting for Katsyv, none other than Natalya Veselnitskaya. For Browder, the actions of this federal police officer were decisive in the adverse outcome of the investigation. The OAG declined to call him as a witness – as Hermitage requested – considering his role “marginal”.

The exclusion of Hermitage as a party to the proceedings means that it now has no status to oppose the restitution of the money seized. Browder tried to file an objection, but in November 2022 the court rejected his application. The court decisionsExternal link were made public in January 2023.

These judgements confirm two main elements of the view of the case taken by the prosecutors. First, that the sole victim of the fraud that happened in Russia is the Russian Treasury. Unlike what happened in other countries, in Switzerland Hermitage was not considered a victim allowed to sue and has thus no status to appeal against the judgements. Second, the Swiss judges concluded that there was no criminal organisation at work. This argument was also that of the Russian authorities. In terms of Swiss law, it means that there can be no confiscation of funds under Article 72 of the Criminal Code, which does allow seizure of all and any financial resources used by a criminal organisation.

Pressure on Switzerland

Given the current climate of international conflict set off by the Ukrainian war, this decision will just increase the pressure on Switzerland. In the US, Mississippi senator Roger Wicker wrote to the American Secretary of State Antony Blinken on Tuesday asking him to intervene so that Switzerland does not just hand back the money to Russia.

The Swiss government is planning to send millions of dollars back to 3 Russians with close ties to Vladimir Putin and who have been tied to the death and torture of Sergei Magnitsky.

— Senator Roger Wicker (@SenatorWicker) February 1, 2023External link

I have urged @SecBlinkenExternal link to demand reassurances these funds will not be returned to Russia. pic.twitter.com/uvjrZSQAToExternal link

“The actions of the Swiss authorities put Switzerland in an isolated position, since most other Western countries are taking a hard line on dirty money coming out of Russia”, Browder told SWI swissinfo.ch.

Having now appealed to Switzerland’s Federal Court, Browder intends to keep up the international pressure on Switzerland. “We will be bringing the issue before the Congress of the United States, the European Union, and governments in Britain and Canada,” he said.

“Our aim will be to get other governments to reclassify Switzerland as a country that facilitates money laundering. The only thing that seems to work in Switzerland is outside pressure.”

He hopes to get Switzerland put on the Financial Action Task Force blacklist as a country facilitating money laundering. He also hopes that other jurisdictions will want to review their treaties of international judicial cooperation with Switzerland.

Edited by Virginie Mangin. Translated by Terence MacNamee

More

Leading Russian opposition figures criticise Switzerland

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.