Market develops for stolen bank data

The case of ex-banker Rudolf Elmer, arrested this week for allegedly breaking the law on Swiss banking secrecy, showcases how vulnerable banks are to vengeful staff.

Swiss lawyer and fraud specialist Christof Müller tells swissinfo.ch that a market has now developed for stolen client data.

On Wednesday, Elmer was given a suspended fine after being found guilty of threatening his former employer Julius Bär and breaking Swiss secrecy laws. Elmer was then re-arrested in Zurich on charges of violating banking laws by handing over two CDs to WikiLeaks on Monday. The ex-banker claims they contain details of around 2,000 offshore bank accounts. In addition, Elmer has appealed Wednesday’s verdict.

The events surrounding Elmer are the latest in a series of cases involving client information stolen from Swiss banks. Data CDs have been offered to several governments including the French, German and Spanish authorities.

swissinfo.ch: Do we know how many cases there have been?

Christof Müller: No, because it’s one of the most unpleasant things for an employer. They want to make sure situations like these don’t do too much damage. And a case becoming public knowledge is damaging.

The very first whistle blowing case in Switzerland involved Stanley Adams and the Swiss pharmaceutical company Hoffmann La-Roche in 1976. He went to the European Economic Coomunity’s competition commission and told them that Hoffmann La-Roche was in breach of competition rules.

Today we are seeing a concentration of cases coming from the financial sector because it’s apparent that a lot of information is readily available.

swissinfo.ch: Why is so much information available?

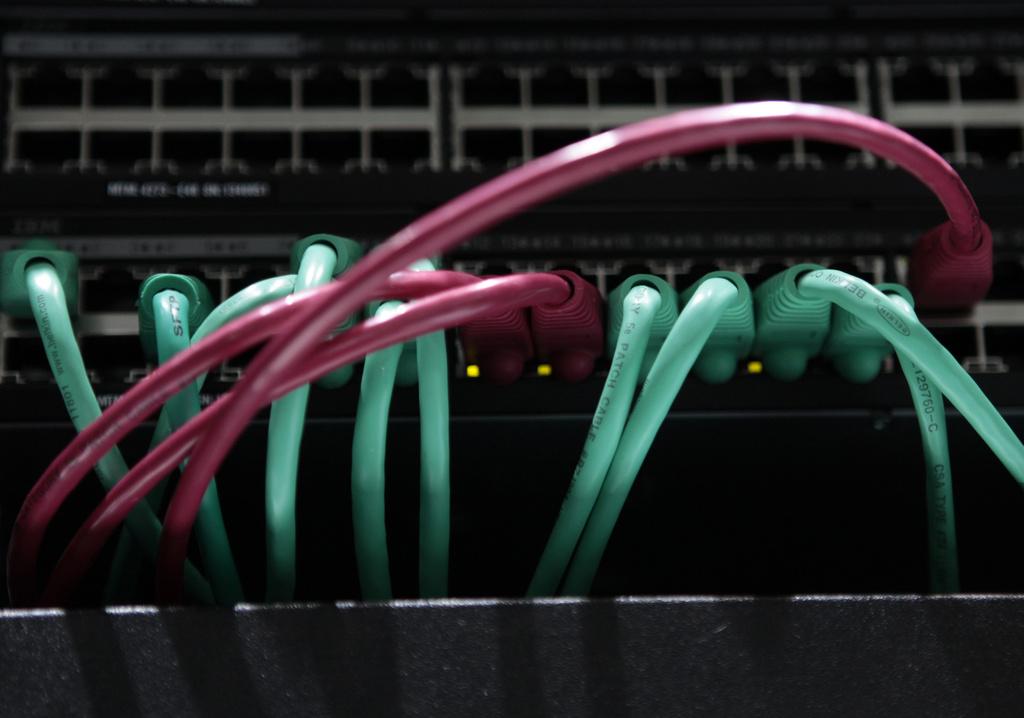

C.M.: Because firms didn’t really know how to protect data internally. We have had several cases where IT specialists took data files and used them in their schemes. This happened in the Elmer case. But no longer are there many instances where bank personnel take data home with them. Switzerland and Liechtenstein have approached the problem and asked themselves how they can better protect their data.

swissinfo.ch: Have they found solutions?

C.M.: Yes. First of all, data is no longer stored in one place. In other words, it’s not kept in one system where it can be gathered easily. And if large data files are ever put together, an alarm goes off automatically. Banks for example have put warning systems in places where large amounts of data are kept together. If printers are used for large jobs, these printing orders are looked at closely. In the front office, attempts are made to ensure that members of staff are only given the information they require, following the so-called “need-to-know” principle.

But the battle has not yet been won because people can use the camera or video functions on their mobile phones to record what passes in front of them on their computer screens.

swissinfo.ch: That means there are still security gaps.

C.M.: There will always be gaps. It’s a trust-based system. Even though murder is against the law, killings still take place – not very often, but they still happen. Therefore if a bank employee lacks ethical principles or has other motives, or ethically sees himself as a whistle blower, it’s difficult to do anything to stop him.

swissinfo.ch: Should we then expect more cases of data being stolen, especially in light of the publicity gained by Elmer when he handed over files to WikiLeaks?

C.M.: The risk has certainly increased because there’s now a market for such data. The message that came out of Germany was that if the data on offer has value, we’ll buy it. A demand has been created, and like any market, whether legal or illegal, demand is met by supply.

It’s just like the market for illegal drugs or human trafficking – these markets also function according to the supply and demand principle. Evidently a new market has come into being because there are buyers for such data.

This data walks out the door of the banks each evening. Every employee brings home knowledge about his clients. Staff members are dangerous when they place their own interests ahead of the banks. Most cases involve employees with personal motives – either personal gain or revenge – as opposed to people who act because they want to call attention to unethical practices.

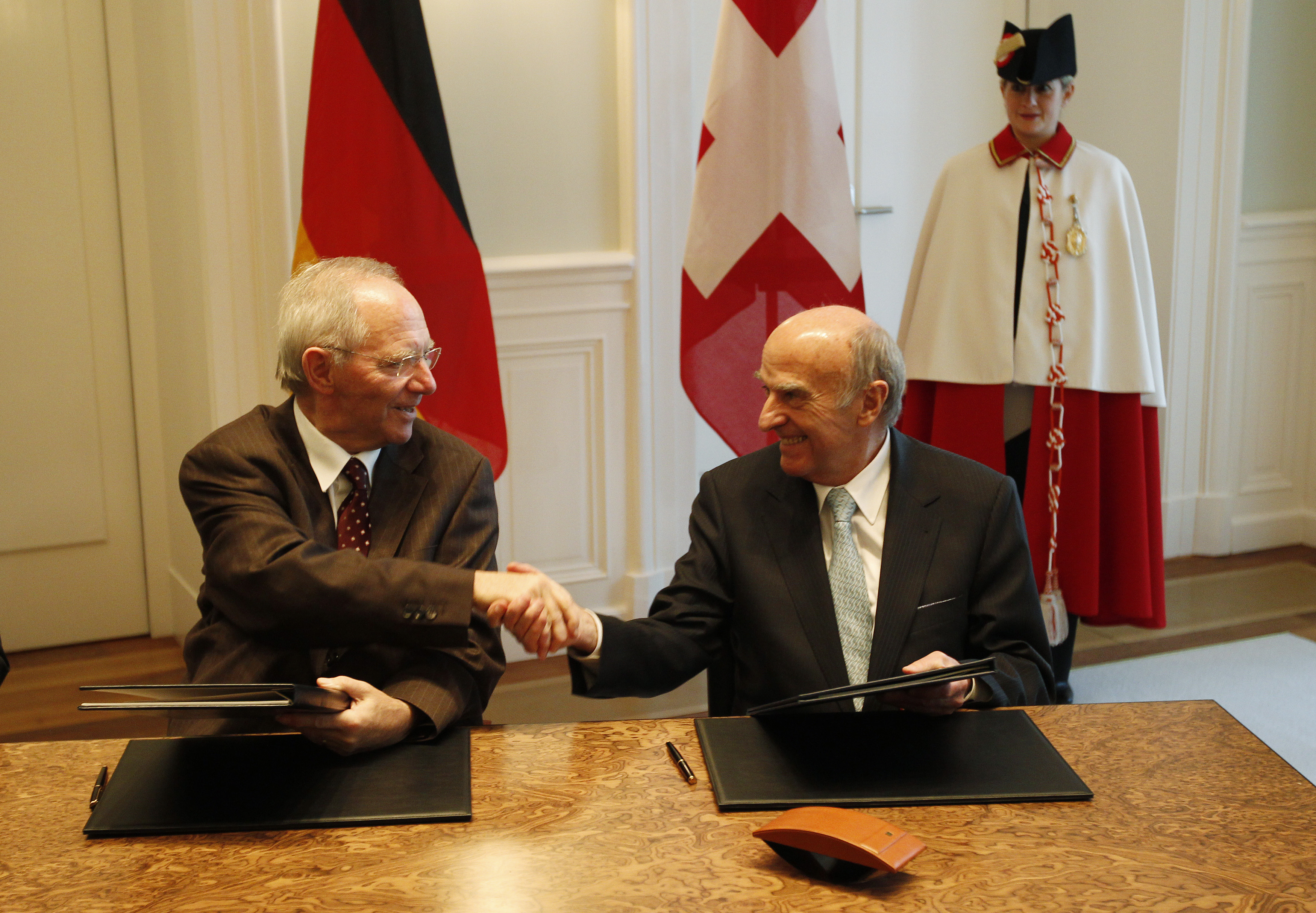

swissinfo.ch: So in representing its financial sector, Switzerland should act as it has been by pushing bilateral agreements with other countries to win assurances that stolen data won’t be bought?

C.M.: That’s at the highest level. But individual banks must act to reduce the risk. The risk is the employee as well as the process and system. The latter two can be made more secure by making access to data more difficult and therefore preventing the removal of entire files.

But when an employee has the time and patience, he can, for example, photograph his computer screen twice every day and eventually put together complete files. In other words it’s impossible to prevent large data leaks. At the staff level, banks must have employees who identify with their company and who can therefore be trusted. They must also recognise when someone is unhappy or anxious, perhaps because he can no longer identify with the ethics of his employer.

The German authorities have repeatedly been offered CDs with data of possible tax offenders. Many who put their money in tax havens to avoid paying tax have since been caught or have given themselves up.

After buying a CD with information on clients and staff at Credit Suisse, Düsseldorf prosecutors began preliminary investigations into about 1,100 cases in March 2010.

The assets are said to have totalled €1.2 billion (SFr1.56 billion). The finance authorities in North Rhine-Westphalia are said to have paid €2.5 million for the information.

The Süddeutsche Zeitung newspaper estimates that in this case more than €1 billion will flow into state coffers.

News leaked in June 2010 that the German government and Lower Saxony had bought a CD in Switzerland with data on more than 20,000 suspected German tax evaders.

The finance authorities in this case estimate additional revenue in double-digit millions. The data was bought for €185,000.

In 2007, data stolen from a Swiss branch of bank HSBC was believed to have contained information on around 24,000 customers.

The data, taken by an IT specialist working at the bank, was offered to the French authorities and eventually to other nations, including Spain.

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.