Microplastics research in the Antarctic often requires creative solutions

In theory, sampling seawater for microplastic contamination is relatively simple: you filter a large amount of water and analyse the particles retained by the filter. But in an environment as pristine as the Southern Ocean, this has turned out to be more complicated than initially thought.

Just last year, researchers from our laboratory in Basel showed that microplastics are present in Antarctic waters, but the concentrations were low: on average, one fragment of microplastic was found in every 25,000 litres of water. However, more than half of the sampled fragmentsExternal link appeared to be paint chips from the Polarstern research vessel on which the team was travelling.

To collect samples, the researchers had used manta nets, which look like a manta ray from above and are towed along the water surface, as well as filters on the ship’s seawater pump. The paint chips were found in both types of sample, indicating that the ship continuously shed paint.

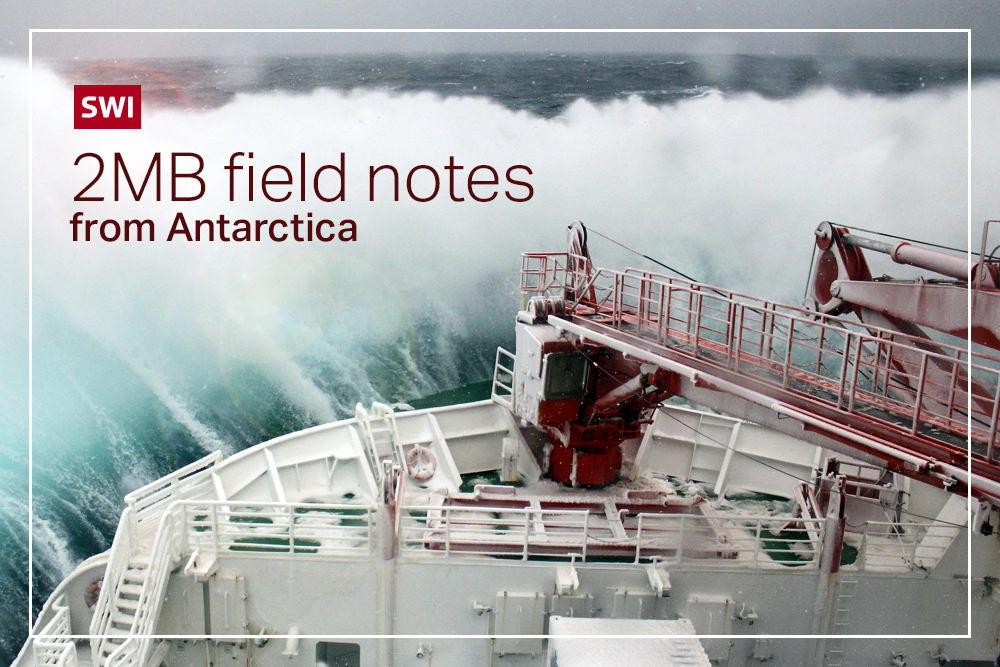

2MB field notes from Antarctica

Just 2MB a day?! That’s the data limit for the authors of our polar blog. This spring, Gabriel Erni Cassola (right) and Kevin Leuenberger (left) from the University of Basel are on board the German icebreaker “Polarstern” in the Southern Ocean. The researchers want to find out how animals and bacteria in the Antarctic are affected by microplastics. In this blog series they give us insight into their work and life on board a polar expedition.

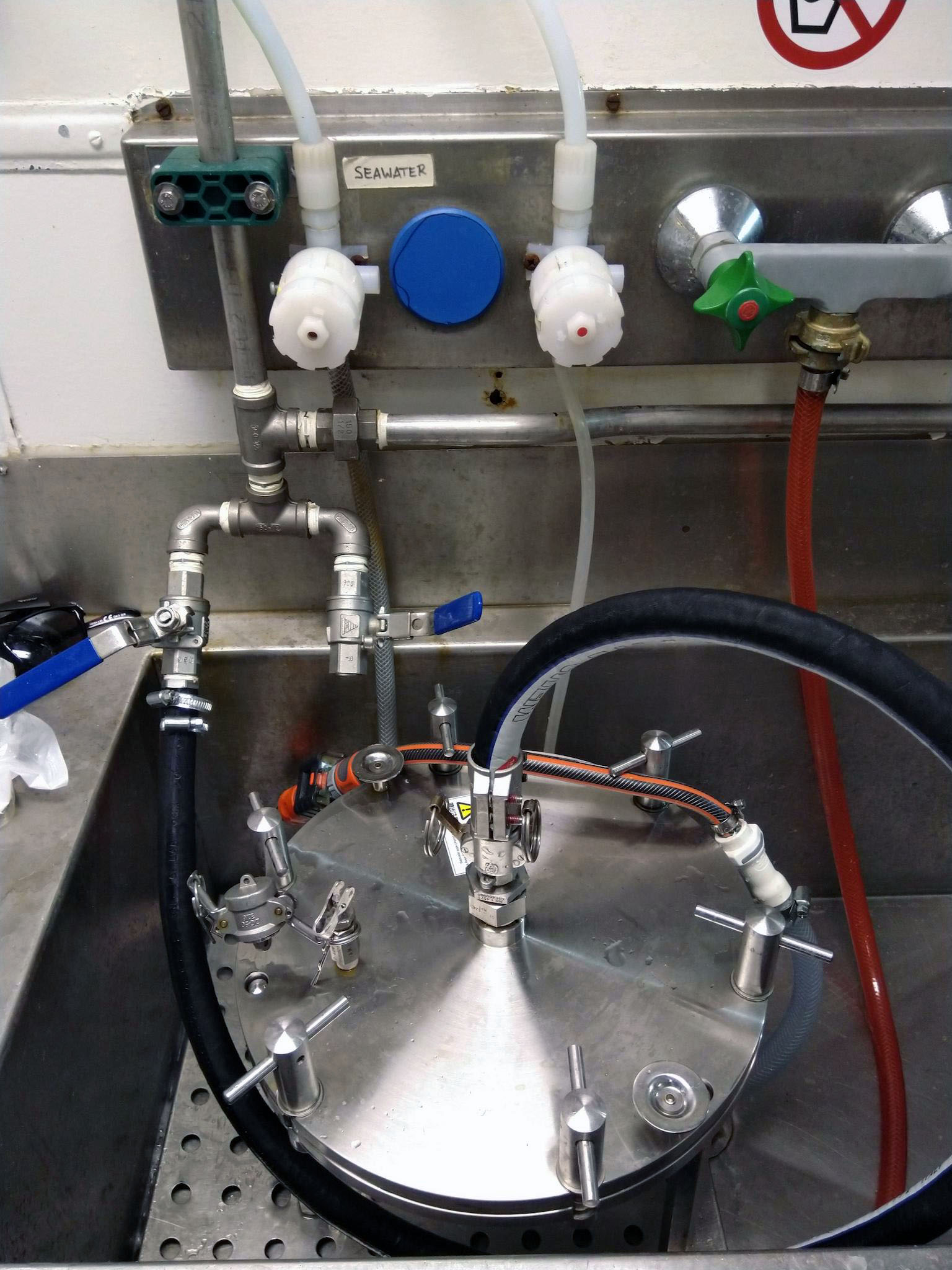

On our expedition, we set out to filter more seawater but using a different method to avoid the problem of the paint particles shed by the Polarstern. For this, we collaborated with other researchers on board who collect water samples via the “moon pool”, a “hole” in the middle of the ship that looks like a well and allows access to seawater from below the keel at a depth of eleven metres. There, the ship’s crew installed a snorkel to take samples of water that has not been in contact with the ship and is therefore not likely to have been contaminated with paint particles.

The new method was promising. But it was a little tricky to find the right adapters to fit our collaborator’s pump to our hoses – sometimes marine science is all about finding the right hose adapters.

This way of collecting water samples can only be done when there’s no sea ice, otherwise the snorkel could get damaged. However, this late in the Antarctic summer, and with storm-related delays, we had a lot of sea ice on our route. After three sampling sessions, we had to dismantle our contraption again, and take the water samples from the ship’s own seawater supply as was done in previous years.

As the conditions on board are not suitable for analysing these samples – the risk for contamination is too high – we won’t know what our samples look like and how they compare to previous studies until we’re back on land.

Our research is also concerned with the microorganisms that colonise plastic found floating in seawater. These form communities that stick to the surface, known as biofilms. Although biofilms form on any submerged surface, it is particularly interesting to study this phenomenon on floating plastic, because in the open ocean many microbial organisms avoid aggregating in the water – they would sink faster otherwise.

Plastic, however, offers a durable raft on which these communities can form and develop. If you picture the open ocean, where rafts are few and far between, this is a rare and unique new environment for microbes. Most studies looking into such microbial communities took place along coasts; what happens in open oceans remains poorly understood.

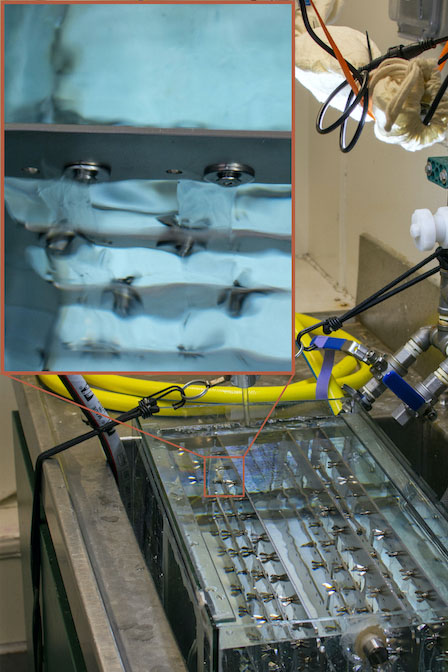

We are investigating what bacteria are present in these communities and how the communities assemble over time. To simulate the floating of plastics on the surface of the water, we use aquariums in the lab on board the Polarstern, into which we can insert frames and attach plastic samples.

We continuously add sea water to the aquariums and take three samples over the course of two weeks. In a further step, we then examine the bacteria by isolating their DNA. This will hopefully allow us to learn how these microbial communities develop and whether they differ across the geographical regions of the Southern Ocean, and how they compare with other oceans, such as the Atlantic.

Scroll down to read earlier entries from Gabriel and Kevin. To receive future editions of this blog in your inbox, sign up for our science newsletter by putting your e-mail address in the field below.

More

2MB field notes from Antarctica

More

Why are we looking at plastic pollution in the Antarctic?

More

Is plastic on the menu of Antarctic fish?

More

When storm ‘Gabriel’ hit the Weddell Sea

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.