Why Swiss cows climb mountains

You would be udderly surprised to encounter a Simmental or Braunvieh running up the steps of New York’s One World Trade Center or Shanghai’s equally tall World Financial Center.

But that’s the kind of climb – albeit on dirt trails not concrete steps – a typical Swiss dairy cow makes every summer.

According to the Federal Office for AgricultureExternal link, around 270,000 cows are marched from their valley farms to mountain meadows at the start of every summer, just to come back down again in early autumn.

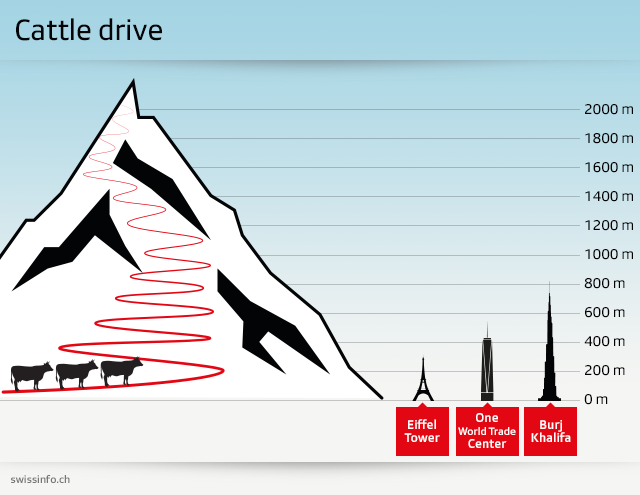

On average they climb about 590 metres (1,936 ft), covering 16.3 kilometres (10.1 miles) as the crow flies – but much more down on the ground on often steep, serpentine trails. The true alpinists among them make ascents of over 2,000 metres. That’s like getting to the top of the world’s highest building, Dubai’s 830-metre Burj Khalifa, and – not satisfied with that – going back down and doing it all over again, and then some.

So why do they do it?

Dairy farmers have incentives to herd their cattle high. On the one hand, they get top dollar for the aromatic “Alp cheese” produced from the milk of their livestock. From June to early September, alpine pastures serve up a smorgasbord of hundreds of different grasses and herbs for the cows to graze on. That’s compared with only a few dozen types lower down in the valley. Whether this improves the flavour depends on your taste buds, but what researchers do know is that Alp cheese is much richer in omega-3 fatty acids, and that, they say, is good for you.

According to the Swiss Association of Alpine FarmsExternal link, around 4,000 tonnes of Alp cheese is produced every year.

The government also encourages farmers to take their cattle up the mountain by rewarding them with a subsidy of around CHF400 ($412) per cow each summer. The postcard alpine landscape of extensive pastures is an integral part of Switzerland’s heritage. The rearing of cattle became the dominant form of agriculture in the Alps as early as the 14th century. It’s probably not a coincidence that the process to make cheese hard was discovered in this period, which meant for the first time that cheese could be transported over long distances.

The subsidies granted to alpine farmers therefore are aimed partly at preserving this centuries-old tradition of pastoral life and preventing the pastures from becoming forests.

But let’s not pretend the cows do all the work. Herdsmen and women tend to the livestock, driving them out to pasture after the break-of-dawn milking and rounding them up in the late afternoon for a second milking. Making cheese from the liquid bounty fills much of the day in between. On average the men and women work 14-hour days, seven days a week, and are paid as little as CHF70 a day for their labour – about a third of the average Swiss salary.

So why do they do it?

It’s the dream of many Swiss to spend the summer in the fresh mountain air on an “Alp” (mountain pasture), milking cows and making cheese. It’s not unusual to find doctors, lawyers and teachers among those signing up for a crash course in herding and cheese making.

But once they drive their cattle back down the valley after a hard summer on the Alp, they often choose not to go back up again the following year.

The cows aren’t given a choice.

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.