National security and the ballot box: an odd couple around the world

Switzerland is an exception when it comes to voting on military affairs. But as international media attention around such votes shows, other countries – and their citizens – are not uninterested in this enviable privilege.

“We would love to have a bigger say on our national security expenditure,” says Lindsay Koshgarian of the National Priorities Project – part of the wide-ranging #PeopleoverPentagonExternal link campaign in the US.

“We can’t bomb our way out of a pandemic,” she says, referring to a recent bipartisan decision in the US Congress to set aside 53% of the 2021 federal budget – $733 billion (CHF661 billion) – for the military.

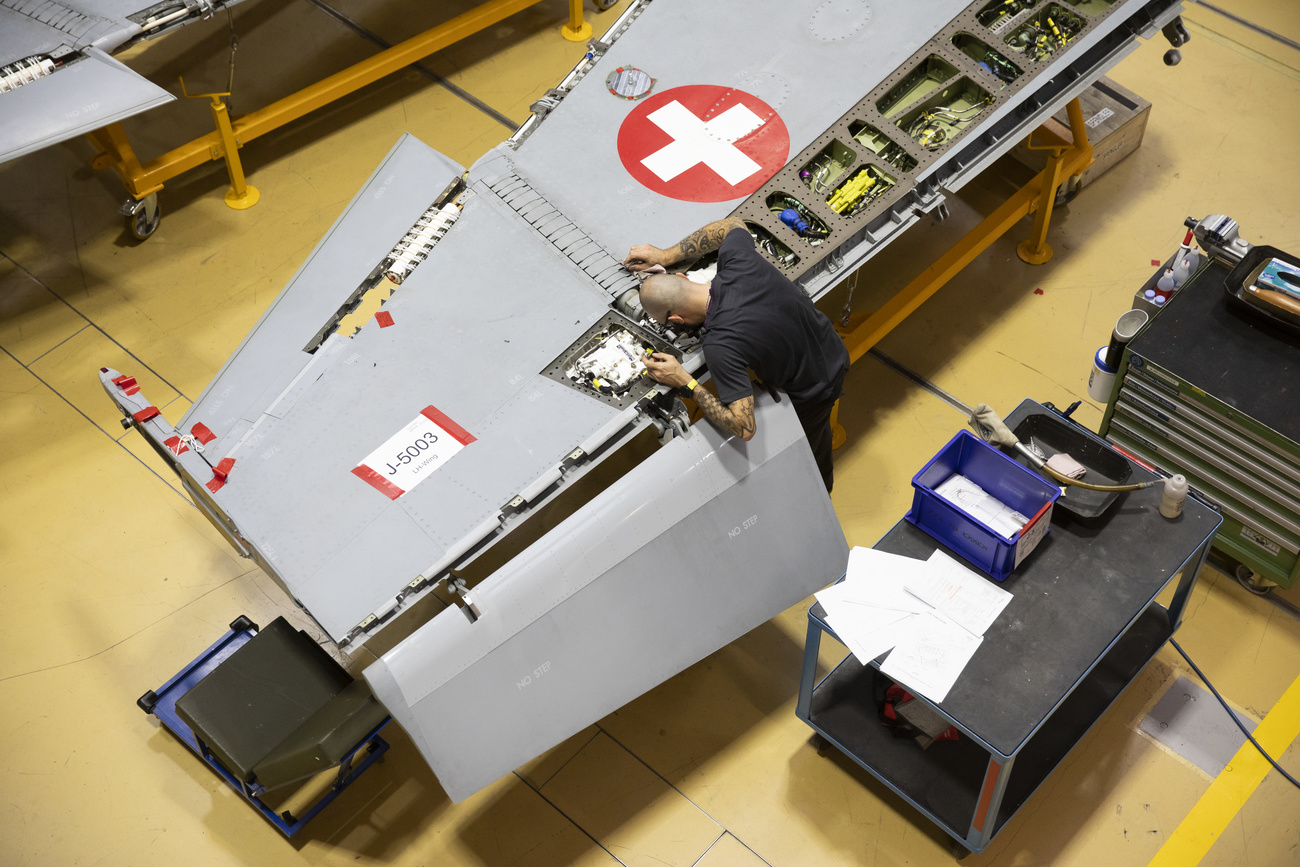

Media around the world are intrigued when it comes to these recurring ballot box decisions in Switzerland: “Battle Around Swiss fighter jet purchase plans heats upExternal link”, “Swiss fighter buy to hinge on 2020 referendumExternal link”, “Swiss to vote (again) on buying new jet fightersExternal link” – just three headlines from international news sites about the September 27 vote on purchasing new military jets for more than CHF6 billion.

Actually voting on national security issues like the air force “should be an obvious matter”, argues Matt Qvortrup, Professor of Political Science at Coventry University.

Qvortrup says there are historical connections between the introduction of compulsory military service and the right to vote in many countries. “Until 1924 in Sweden, men only got the right to vote if they served in the national military,” he says. A series of countries have also held nationwide popular votes on the issue of military conscription, including Iceland (in 1916, when 92% said no), Australia (1917, 54% no) and Canada (1942, 66% yes).

In Austria, a government-initiated “consultation” on the issue of abolishing the mandatory military service in 2013 showed a 60% majority in favour of keeping it. Ten years earlier, a citizen proposal to hold a referendum on new military jets gathered the backing of about 10% of eligible Austrian votersExternal link. Unlike in Switzerland, however, such initiatives do not automatically lead to a popular vote.

US proposal for national war referendum

Another major historical effort to link direct democracy with national security happened during the interwar period in the US.

“The argument was that ordinary people, who were called upon to fight and die in wartime, should have a direct vote on their country’s involvement in military conflicts,” says Qvortrup.

A constitutional amendment – the so-called Ludlow amendment – was discussed several times by Congress, with debates held on whether “any declaration of war by Congress should be foregone by a national referendum”.

However, while opinion polls showed public support of 75% for the amendment, it never gathered the necessary two-thirds majority required in both chambers of Congress.

In contrary to popular votes on European affairs – like the upcoming ballot on the free movement deal with the EU – where Switzerland and its European neighbors are often on the same page, national security referendums have been a rare species around the world since the 1970s (a period during which more than half of Switzerland’s 45 nationwide national security votes have taken place).

One exception was in post-authoritarian Brazil: in 2005, almost two thirds of voters rejected a proposal by the government of then-President Lula da Silva to ban the sale of private guns.

“It was a half-hearted attempt to apply a tool of direct democracy to demilitarise the country”, says political scientist Rolf Rauschenbach, who has published extensivelyExternal link on democracy in Brazil. “After this defeat the labour party lost all its ambitions to boost citizen participation in the country,” he says.

Today, Brazil is ruled by a former military man, Jair Bolsonaro, with key cabinet posts also occupied by army officers.

Democratic control of armed forces

There was more direct democratic success on the other side of the globe, in Taiwan, where the very first countrywide popular vote also dealt with a national security issue. In March 2004, more than 90% of participating voters approved a “peace referendum” initiated by President Chen Shui-bian. However, as less than 50% of the electorate participated in the vote, the result was not valid. But instead of giving up on ambitions to empower citizens on major national policy issues, Taiwan continued to beef up its participatory toolkit.

“Our ambition has been and still is to become a beacon of people power in Asia”, says Michael Kau, the former president of the Taiwan Democracy FoundationExternal link. By now the Western Pacific island state has held dozens of national votes and become a poster child of vibrant democracy in the region, in spite of ongoing external challenges to national security.

Finally, while the use of direct democratic tools to regulate national security issues remains an almost exclusively Swiss habit, one of its domestic initiatives has spread around the world. Twenty years ago, the Swiss government established the “Geneva Center for the Democratic Control of Armed Forces” (DCAFExternal link), with the purpose of improving democratic governance in security sectors.

This international organization today has more than 60 member states and – as its Director Thomas Guerber underlines – has become “a vital pillar of peace” in the world.

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

Join the conversation!