Peter Zumthor’s key building material is light

Internationally celebrated Swiss architect Peter Zumthor turned 80 this year with major works in the spotlight and in progress. Forty of his architectural models were showcased in a special exhibit held in a building that Zumthor designed in Austria’s Bregenz Forest. Two museum buildings by the designer are due for completion in 2025 in the United States and in Switzerland. Light is an essential building block of all his creations.

Swiss architecture giant Peter Zumthor celebrated his 80th birthday this year in the company of his family and in the country where most of his creations stand – in his native Switzerland. Originally, before the pandemic, the spring 2023 celebration had been planned in the new Los Angeles County Museum of ArtExternal link (LACMA), where a new building designed by Zumthor is currently in the works.

The journey to the United States would have been a long one, including for his three children and now six grandchildren. But that wasn’t why the plan was scrapped.

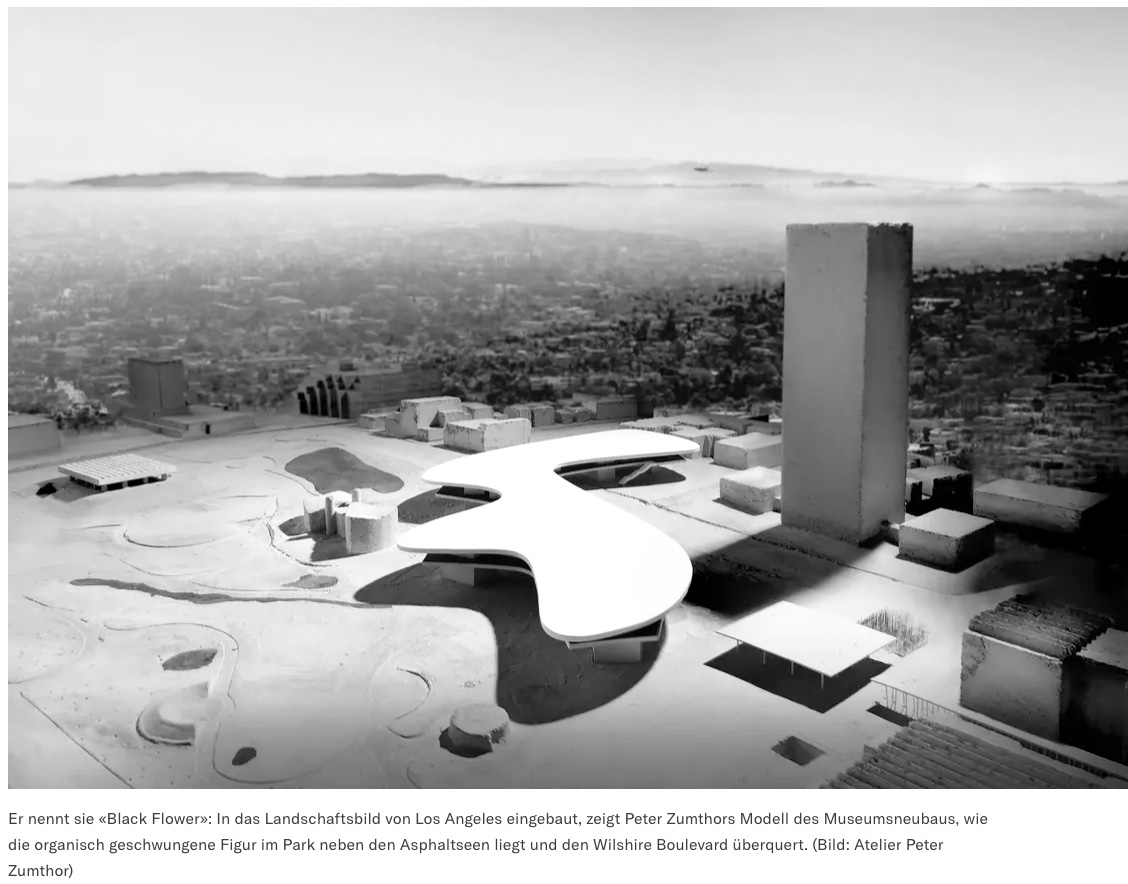

Supply difficulties due to the pandemic, archaeological discoveries in the Tar Pits (the black asphalt lakes that dot the museum site in Los Angeles), and other delays meant that Americans must wait a little longer before they can experience Zumthor’s largest museum building to date.

The new LACMA building probably won’t be finished until 2025. The same applies to Zumthor’s other on-going building site for another internationally important museum, the Fondation Beyeler in his hometown Basel

Radiant stones

Both museum buildings will be stone-clad. LACMA will gain a kidney shaped figure of exposed concrete, Fondation Beyeler a monolith poured in a Jurassic limestone mixture. Their radiance is drawn from a tranquillity that is accentuated by light, freeing up a space for art. The parallels don’t stop at the facades or the construction schedules, but also extend to the general settings. In both museums, Zumthor’s architecture complements buildings conceived decades ago by Italian Pritzker Architecture Prize winner Renzo Piano.

The prize, considered the most prestigious in the architectural world, was awarded to the then 66-year-old Zumthor in 2009, 11 years after the honour went to Piano, leading to a surge in commissions for the Swiss architect from across the world. Despite his international fame, he still heads a modest studio in Haldenstein in the canton of Graubünden, a couple of minutes drive outside Chur in a village with a castle set against a picturesque mountain backdrop.

Born and bred in Basel, the architect moved to Switzerland’s easternmost canton in the 1970s. In Graubünden, he built houses for his work colleagues and family, and then set up his own studio. International recognition came in the mid-1990s, triggered by his consummate staging of the mountain stone of the Vals Valley from the quarry of the family Truffer for the ValsExternal link thermal baths. Unlike the Truffer company’s own “anti-object” by the Japanese architect Kengo Kuma, with its “floating stones”External link, the stones in Zumthor’s thermal baths are earthed, as if hewn directly from the cliff face. The stones are layered around the water pools as if held solidly in place only by their apparently infinite weight.

The rooms are tranquil and ponderous. They echo. There is music – another of the designer’s passions. Many view him as a native Graubünden architect given that he has worked for half a century in and around Chur. There, surrounded by friends and acquaintances, by books and music, he works away in his studio with views of the mountains.

A virtuoso in all repertoires

Monumental stone is only part of Zumthor’s repertoire as a leading architect. Over ten years after his masterpiece in the Swiss mountain village of Vals, he created another international landmark building with the Art Museum of the Archdiocese of Cologne, Germany. Named after the sainted martyr with the onomatopoeic name Kolumba, the building weaves light and stone in a play of architecture that at times seems to defy gravity.

What’s more, this is a melody that Zumthor can play with any material. It was performed in wood in 1989 in the Chapel of St Benedict in Surselva in canton Graubünden, and later in the resonating volume of the Swiss Pavilion at Expo 2000 in Hannover, where stacks of timber planks created spatial rhythms.

Sometimes things go wrong. This was the case in Berlin with Zumthor’s winning 1993 entry for a monument in memory of the terror of the National Socialist regime. The project ended in a half-finished concrete shell and unleashed a long-running row that only ended in 2004 with the demolition of the ruin and a financial settlement.

On the other hand, a later German project, the Bruder Klaus Field Chapel in North Rhine-Westphalia, is far smaller and nevertheless world-famous. A direct commission, the result is a tall volume constructed in tamped concrete, within which over one hundred spruce trunks were burnt to create an almost indescribable interior atmosphere. Unfolding from the charcoaled, patterned surfaces is a space that is both sensuous and contemplative in one, an effect that always resonates in all of Zumthor’s works.

Models as tools

Zumthor’s architecture doesn’t shy away from pathos. At the same time it always strikes fine tones. It is an architecture of the senses, but also designed using the tools of sensation. The materials not only play an important role in the finished buildings but also in their process of formation. At the exhibit, the expressiveness of the models from Zumthor’s studio go beyond the material. As the key instrument in developing the project they speak for themselves, devoid of any other words.

The Swiss architect’s range of materials is large. Apart from wood and loam, he also uses exposed concrete, as evidenced in Austria’s Kunstmuseum Bregenz (KUB), an early and significant work from 1997.

The Bregenz museum building is a cube of etched glass, where light plays the main role, both in the interior and the exterior. Outside, the surface catches the ever-shifting moods of the sky and the surroundings; inside, it filters and funnels the light so that it falls evenly on the illuminated ceilings set in the raw concrete of the exhibition spaces.

Zumthor has also exhibited his own work in Bregenz before, providing a panorama of his interests and references. That was six years ago, during the KUB’s 20th anniversary, when he invited prominent figures from the fields of literature, art and philosophy to together reflect about the world.

This exchange of ideas was later published as a book with the title Dear to Me (in German and English, Scheidegger & Spiess, 2021)External link. These printed dialogues with other artists and intellectuals transported and harmonised the cultured world of art and the material world of building in a way that very few other architects had managed to do before.

The Werkraum Bregenzerwald [Bregenz Forest Workroom], an association promoting crafts and building cultures, put Zumthor’s designs at the heart of a six-month exhibit that ended in September 2023. His 40 handcrafted models – some never presented to the public before – graced 700 meters of indoor and outdoor space. True to his style, these experimental setups conveyed an atmospheric intensity that responds to the building’s functionality.

Uncompromising

The interplay of shadow and light is another primary architectural ingredient for Zumthor. The interaction of the two is evident in the shadows that balance the stone in Vals and Cologne, that lets the wooden planks in Hannover float, and that defines the contours of space in Basel and Los Angeles, although both the designer and the public will have to wait to see the impact of the last two projects.

To see their work acknowledged in their lifetime is a privilege that architects get to experience more often than might otherwise be expected. Planning and building are lengthy processes. At the same time, and despite all his international accolades, Zumthor’s oeuvre has remained relatively manageable to survey, not least because compromises have never been to his liking.

Sabine von Fischer is an architect and architecture critic. In October 2023, a selection of her texts will be published under the title “Architektur kann mehr. From Promoting Community to Decelerating Climate Change” by Birkhäuser Verlag.

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.