Gallus and the Irish monks: grandfathers of European culture?

After the fall of the Roman Empire, Europe was plunged into the Dark Ages. It might have fallen further had it not been for the epic efforts of a band of Irish monks.

Take a walk through the vast courtyard of St Gallen Abbey. The stone church towers stretch 68 metres into the sky, clichés of clanging bells sound out, a scent of hot waffle drifts from an old cafe. A few bemused Asian tourists stroll around. It’s difficult to imagine things were ever otherwise.

But the history of the Abbey—and of founding father Gallus—is one of constant change. Enzo Farinella, a Dublin-based Italian scholar, says it is also an inspirational story, one that needs to be retold for a modern and troubled Europe. He recently did so, with a book about the impact of Irish monks on Swiss history (“On the Summits of the Highest Love”).

Hibernian roots

It all begins in Ireland, he writes. 590 AD. Cold, wet, bogged, forested. A period of history hovering between Romans and Renaissance, under the gathering clouds of the Dark Ages. Pagan tribes competing for influence on this small island on the edge of the known world.

Pious bands of monks are scattered through the country. Vows of silence, seclusion. Sheltering from savage Viking raids in purpose-built round towers. They spread along the coasts, fusing early Christianity with liberal traditions of Antiquity, developing a culture that will turn the island into a beacon for dark times.

The island can’t contain them. They want to spread further, to take the word to the continent. Peregrinatio Pro Christo. Long before the waves of forced exiles from a hungry nation, they go with God’s purpose. A group of thirteen, led by Columbanus and his closest disciple Gallus, board a wooden ship, sail out into the Irish sea.

Quickly across Britain. Two decades in the northern territories of France, running skirmishes and conversions with the tribes until expelled by a local king. Go back to your own country, the king says. But they go south. Down the Moselle, along the Vosges, across the Rhine, glimpse the Alps, arrive at Lake Zurich.

The idea of Switzerland won’t be born for another four centuries. They find a mish-mash of tribes, German and Romansch dialects, heathen practices, a land for grabs after Rome’s downfall. Charismatic Columbanus woos some locals, scares off others. His twelve followers convert, teach, travel, found monasteries. Miracles are performed.

Again a jealous ruler expels them, the vicious Queen Brunhildis. Columbanus continues south, crosses the Alps. 610 AD. Rome, Lucca, Firenze, Bobbio, the most important monastic settlement in early Europe. Founds a famous library, saves copies of Cicero and Virgil from oblivion. Writes of Europe as a common cultural entity, the first on record to do so.

Gallus goes it alone

But Gallus? The favourite disciple can’t continue. He stays, sick, behind the Alps. Sick, or providentially divined? Farinella wonders (tongue-in-cheek) if it was “one of the mysterious ways by which God guides his people as he likes”. Gallus is the perfect missionary, a gifted communicator. He can talk to everyone. Gallus has gall.

He reaches the shores of Lake Constance, north-east Switzerland, 612 AD. Trips over a thorn bush. Another accident? This is where I will found my monastic cell! he declares. He tames a bear, fishes a waterfall, recovers health. He gathers followers, prays, writes, teaches. Patiently. The monastery grows.

His reputation grows. Monks travel from far and wide to learn from him. He is asked to become bishop of the burgeoning monastery. He is asked to become abbot of Luxeuil in France, Columbanas’ old stomping ground. No, he says. He just wants to be a monk. To pray in solitude. So they make him a saint.

The monastery grows. Europe sinks further as the power vacuum left by Rome sucks in barbaric tribes and jealous princedoms. Gall dreams that Columbanus has died in Bobbio. He has. Gall’s legend grows. He founds his own scriptorium in the footsteps of his mentor. A music school will follow.

The monastery grows. 645 AD, Gall dies preaching, allegedly 95, a ripe age in these times. The foundations are laid. Two centuries later the abbey is the chief centre of learning and teaching in all Germanic Europe. Already named after its founder. Already attracting illustrious scholars from across the continent. Droves of pilgrims—the world’s first tourists—help pay the upkeep.

The new town of St Gallen spreads around like a lay overcoat. Tensions arise, are smoothed once monies and power are mutually assured. Manuscripts, gospels, the story of Gallus himself, are written in the library by Irish hands. Precious records of a time when learning was scarce, preserved learning scarcer.

Surviving modern times

1291, Switzerland is born. The legend of Gallus rolls on. St Gallen remains one of the most important centres of Christianity on the continent. The Dark Ages move towards a close. 1517, Luther pins his theses, the Reformation rears its head, the Catholic abbey is surrounded by a Protestant sea. It fights its corner. Preserves its place, imports ever more riches to the renowned library.

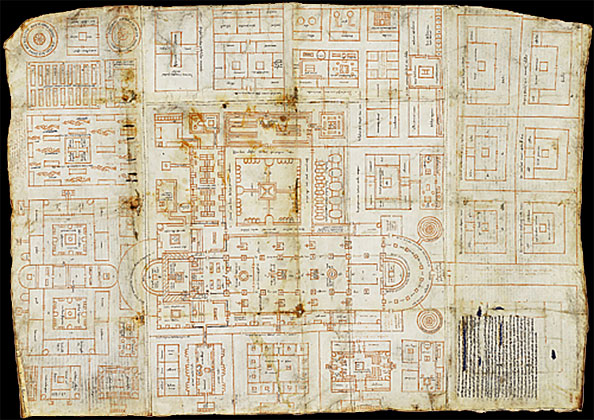

The Renaissance arrives, is built upon the classic Christian ideas the Irish monks sought to spread in the first place. Baroque masterpieces by local artists and architects adorn the growing and glowing cathedral. The inner dome (see photo) offers weary locals a glimpse of heaven.

1798, France stages a revolution. Religion falls out of favour. St Gallen sits on the faultline between secular French control and the monarchist Hapsburgs to the east. The French clinch it by a hair. The monastery is shut down, the monks chased out, the abbey secularised. But survives.

A boys’ school is opened. Modern tourists come in waves, from east and west. 1983, UNESCO recognises the indisputable impact of Gallus on the course of European culture. 2012, the abbey celebrates 1,400 years since the visionary monk tripped over his thorny root.

Today, 2018, the abbey plans an international exhibition of manuscripts to show the contribution of Irish learning to Christian Europe in the Middle Ages. To show how the monks brought new forms to writing, saved certain areas of learning.

But the message is even more than the medium, says Farinella. The monks left Ireland for Europe to “rebuild the human aspects of humanity” through their teaching. To provide the missing link between classical Europe and the modern Christian entity of today.

And so he wrote his book “to trace and elucidate [the monks’] work, and by doing so, remind our European Union, Switzerland included, of its cultural, historical and religious roots.”

A big idea. Gallus would be proud.

More

Switzerland celebrates its heritage sites

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.