Robots will help us manage Covid-19, but not in the way we think

Brad Nelson, a robotics professor in Switzerland, had been planning to install a robotic catheter system in China at one of the world’s largest hospitals when the Covid-19 crisis hit.

Soon after, Nelson and his team at the federal technology institute ETH realised that the robotic catheters designed to protect surgeons from harmful x-rays during brain operations had unintended benefits against the novel coronavirus.

“We discovered that using remote robotic systems that allow the surgeon to perform procedures outside the operating room could also prevent the transmission of Covid-19”, Nelson told swissinfo.ch.

Surgical robots have been around for decades to perform minimally invasive surgeries that can help patients recover faster. Similarly, industrial robots have been assembling cars in factories for years.

But amid the pandemic, robots could bring back some sense of normalcy by doing essential tasks that have become too risky for humans, and relieve us from other, much more mundane chores.

“It became clear very early on that the reason to have robotics in the first place is exactly because of situations like Covid-19. This has put even more focus on the types of robots and services we can provide”, Peter Fankhauser, CEO of theSwiss start-up ANYbotics, told swissinfo.ch.

His company is one of many catering to humanity’s new need for robotic help. The Robotics for Infectious Diseases,External link a new consortium of roboticists addressing Covid-19, found reports of more than 150 waysExternal link robots are being used in Covid-19.

In different countries, disinfecting robots with UV lights have been sweeping through hallways in hospitals and schools, four-legged robots have been delivering packages to doorsteps, and robotic dogs have been spotted monitoring social distancing in parks.

Beyond the hype

The pandemic arrived at a time of huge advances in the robotics field with the rise of AI and machine learning.

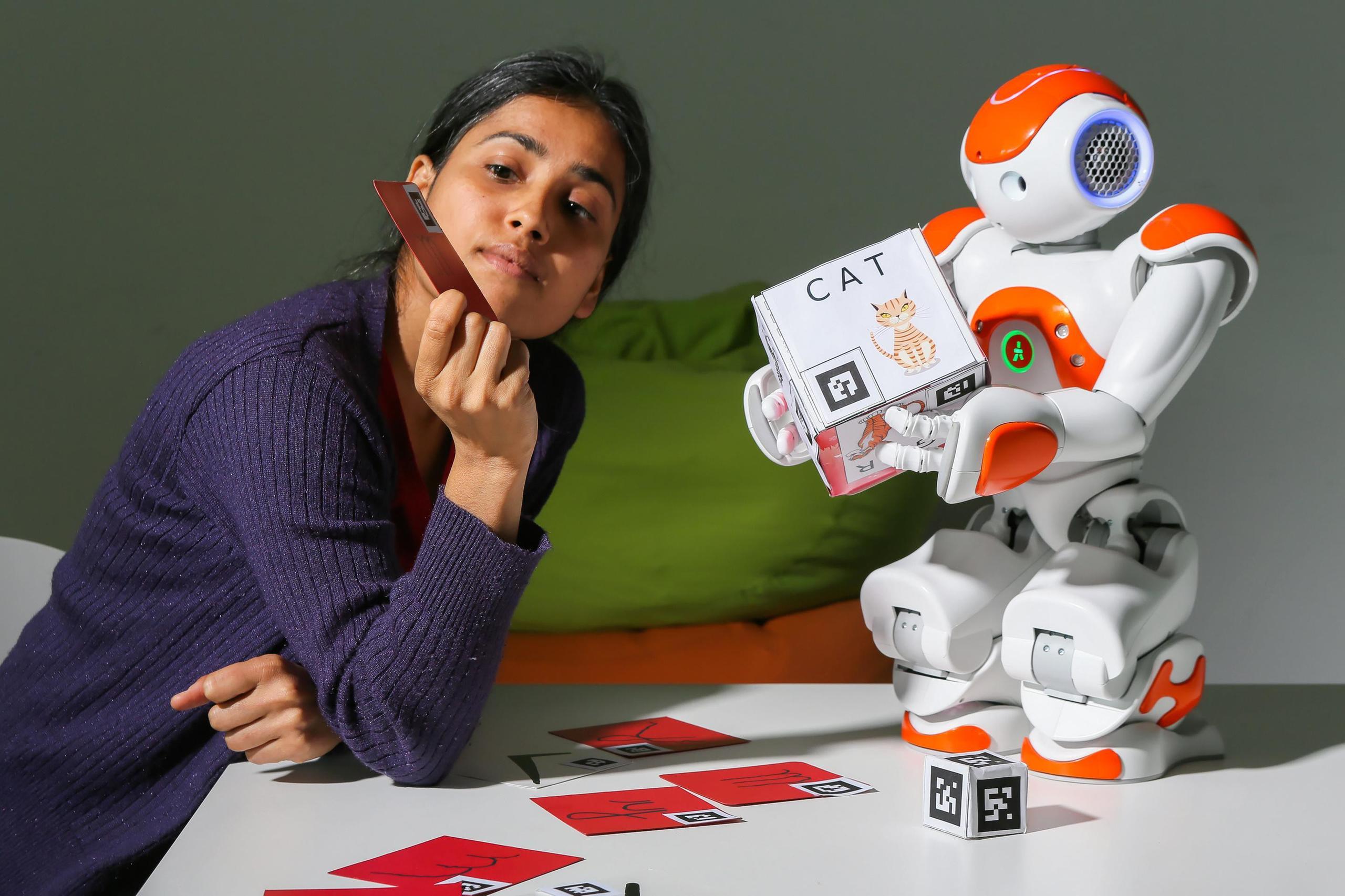

In Switzerland, the field has been booming. Researchers and start-ups like Sensars and MyoSwiss are developing wearable or prosthetic robots. Flying robots like Dronistics can undertake rescue missions. Educational robots are teaching computational thinking and engineering.

When the pandemic spread, Dario Floreano, who heads the National Centre of Competence in Research Robotics, and colleagues gathered to think about ways Swiss researchers could contribute to tackling the global scourge.

“We could develop a lot of technology solutions, but the last thing people need is to figure out a new technology,” he said. “What we need is to figure out how to apply the ones we have. It wasn’t the time to send experimental prototypes into the field.”

Some of these reservations to push robotics too hard stemmed in part from some of the misconceptions about where robots can really make a difference and where they’re mere gimmicky hype.

Earlier this year, the Idiap Research Institute in Martigny in Canton Valais showed off a robot that makes raclette cheese at the Consumer Electronics Show in Las Vegas.

It grabbed attention, but the intention was never to replace the person who makes the raclette, said Sylvain Calinon, the team leader. “It started as a joke. Living in the Valais, I know that a robot can never replace that special interaction you have with the person who makes your raclette.”

But the point was to start a conversation about the technology that is powering the robot in a way that was easy for people to understand. As the cheese melts and is scraped off onto a plate, the robot must adapt to the changing weight and shape of the cheese. The robot is programmed to learn from demonstration whereby a person guides the robot by hand, or the robot observes a person’s gestures, and then imitates them.

The technology could be applied to many areas such as getting dressed.

The Idiap team has been working on such a use case as part of I-DressExternal link, a project that uses robot assistants to help someone dress, including health care workers, who have to limit physical contact with garments to avoid contamination.

“The robot has to adapt to the needs of an elderly person, which are different than a young person who was injured in a sports accident,” Calinon explained during a visit to the research institute.

Danger zones

ANYbotics’ four-legged walking robots have been used for routine inspections and to solve maintenance problems in industries such as offshore and onshore energy, chemical production and construction sites.

Since the Covid-19 outbreak, it has been receiving requests for their four-legged robots to disinfect spaces in public buildings such as schools and hospitals that have stairwells.

There, previously harmless tasks carry serious health risks. This makes autonomous robots designed for places too dangerous for humans more reliable, and cost-effective.

“Routine inspection in industrial environments continues to be our focus but the sky is the limit in terms of applications,” Fankhauser said. The company is also working on using the robot for delivery services for packages from warehouses to customers’ homes in difficult to reach areas.

Demand for such services has been given a boost by the rise in use of teleconference and telepresence during the pandemic. The initial impetus for building teleoperating functionality was to keep surgeons safe and out of warzones. This eventually led to the creation of the Da Vinci surgical system that is used in more than 60 countries.

About a decade ago, there was some effort to make telepresence robots that essentially move around, monitoring patients and allowing them to talk to their family. However, the idea hadn’t really taken off until Covid-19 said Nelson.

With the pandemic, this changed. In Italy, robots named Tommy have been doing the rounds with nursesExternal link to help take patients’ blood pressure and check oxygen levels.

Fear of obsolescence

Despite the potential, experts warn that developing robots exclusively for the purpose of tackling the pandemic is the wrong approach. The robotics industry learned this lesson during the Ebola outbreak when the United States government and the US National Science Foundation discussed ways robotics could help stop the transmission.

“As the pandemic waned, the ideas became less interesting and didn’t get any traction,” Nelson said. But Covid-19 is different as it has restricted daily activities much more, opening the door for robots.

Another challenge is finding investors other than governments. The economic downturn has already complicated financing for robotics start-ups as investors focus on keeping existing companies afloat.

This is one of the reasons Calinon’s team is prioritising flexibility both in the back-end programming and its robots’ range of use.

“We don’t want to put all of our efforts in one specific application,” he said. “Maybe tomorrow there is another problem, but something completely different.”

What is challenging, Calinon said, is that there is an immediate widespread need. “When something is at the stage of a research project, usually it’s quite complicated to move it to the terrain in the same week or the same month.”

It took 15 or so years for the Roomba vacuum cleaning robots to come on the market. The development timeframes has shortened to five to seven years in many cases, but robots still require lengthy testing and safety inspections before they are ready for use, especially when they have to interact with humans.

Robotics perhaps more than many other fields has had to fight back images of robots that are out of control. One malfunction in a hospital or a school could have lasting consequences for people’s acceptance of robots.

“For start-ups, accidents can be disastrous from a business perspective,” said Floreano. They are just starting to grow their business so it can be difficult to absorb the blow.”

Reality check

The robotics industry also has to contend with concerns about making some jobs obsolete at a time when unemployment is skyrocketing in many countries, including Switzerland.

In a recent op-ed, J. Jesse Ramírez at the University of St Gallen argued that robots have not actually saved us in this pandemic because they can’t truly replace essential human labor.

The pandemic has underscored how important essential workers are, many of whom have been underpaid and undervalued for a long time, he said. He is suspicious of the idea that our problems afford a technical fix.

“I’d like to see the people who do the work leading discussions about if and how their work can or should be automated,” said Ramírez.

Robot experts dismiss fears of mass unemployment from robots. Fankhauser said that people often ask him when they would see robots on the streets or delivering food. But he didn’t think that was the way robotics would evolve anytime soon.

“I think it’s going to be much more that someday you’ll have ten robots in the sewage systems in Zurich instead of having people down there,” he said. “They are going to be out of sight a lot of the time.”

He admits that there is also more apprehension about robots everyday life in Switzerland than in countries like Japan. He tries to describe robots more like smart tools and to be transparent about what they can and can’t do.

Some experiences and interactions in life are irreplaceably human. Using robots might have benefits from an infectious disease standpoint but humans need physical contact.

“We need touch. We have that sensitivity to touch and feeling, that tells us how we can expect someone to behave,” Nelson said. “To encode that in a machine is challenging for engineers.”

More

Where are the robots?

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.