Russia-Iran: how the wheat trade is flourishing despite sanctions

Russia and Iran, both under international sanctions, are intensifying ties with each other. This includes the trade in wheat, with transactions going mainly through Switzerland. While the business is permitted for humanitarian reasons, it’s a sensitive issue.

“Just because a country is sanctioned, it does not mean that trade goes away,” said Sharif Nezam-Mafi, chairman of the Iran-Switzerland Chamber of Commerce, at a recent grain conference in Geneva. “What we see is the emergence of a sanctioned bloc with parallel systems.”

He was speaking to a crowd of business executives who had gathered to explore challenges and opportunities in the Iranian grain market. According to the Swiss Trading and Shipping Association, 80%External link of the world’s cereals are traded in the Geneva region by the top five commodity houses — Archer Daniel Midlands (ADM), Bunge, Cargill, Cofco, and Louis Dreyfus.

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine prompted a series of sanctions on Russian individuals, companies and trade by the European Union, the United States and wealthy G7 nations. Switzerland has kept in line with the EU, implementing its tenth package of sanctions in March.

That has not stopped the international community — including NGOs and more recently the G7 — from criticising Switzerland for not doing enough. They particularly point the finger at the limited amount of Russian assets frozen in Switzerland and argue the Alpine nation could do a better job enforcing sanctions.

In this series we look at what steps Switzerland has taken to conform to international standards and where it lags behind. We question the grounds for sanctions and their consequences for commodity traders based in Switzerland. We also analyse Russian assets in the county and understand how some oligarchs are navigating sanctions.

Western sanctions imposed on Russia after its invasion of Ukraine in February 2022 have coincided with a severe shortage of wheat in Iran that has sent imports from the world’s largest exporterExternal link of the grain through the roof. Registration by Russian companies for an annual grain conference in Iran soared this year, Nezam-Mafi said.

Iran has also been under international sanctions on and off since 1979. The latest round of sanctions was imposed in 2006 after the country refused to halt its uranium enrichment programme.

Trade in agricultural goods is exempt from international sanctions on humanitarian grounds (see box). In Geneva, traders confirmed that the major agricultural merchants and inspection companies all have licences that allow them to facilitate wheat trade between Russia and Iran, as well as maintain a presence in Tehran.

A humanitarian licence to trade

Iran’s domestic grain production was devastated by drought in 2021External link, forcing it to turn to imports to make up the shortfall. The Middle Eastern nation became the single biggest buyerExternal link of Russian wheat in the months after the invasion of UkraineExternal link, when Russian exports temporarily crumbledExternal link as banks and shipping companies were unsure how to react to international sanctions.

In July 2022, the US Treasury Department expanded its general licences on agricultural transactions, reiterating that grains are not targeted by the sanctions regime against Russia. A fact sheet on food security stipulates that the US aims to bring essential goods like wheat to world markets in order “to reduce the impact of Russia’s unprovoked war on Ukraine on global food supplies and prices.” An earlier communication, issued during a period of sky-high global wheat prices in April 2022, clarified that the US did not intend to stand in the way of agricultural exports.

Switzerland followed through in August 2022 by adopting new rules to allow for transactions with Russian companies if necessary for humanitarian trade. The Federal Council also introduced the possibility of unfreezing assets of sanctioned entities if deemed essential for wheat transactions.

Shipments have recovered partly as Moscow has worked to diversify its export markets. But Iran has remained one of the top three destinations, accounting for 15% of its overseas sales of the grain in calendar year 2021 and 13% in 2022, data from the commodity tracker KPLER show.

In previous periods of domestic shortages, Iran imported wheat from a variety of sourcesExternal link, including GermanyExternal link. But in the past two years, its dependence on Russia has surged, with 83% of its wheat imports coming from the country in 2021 and 72% in 2022, according to data compiled by KPLER.

The “big five” grain traders are reluctant to discuss the topic openly. When SWI swissinfo.ch asked ADM for a comment about its activities, a spokesperson would only say that the company “does business globally, connecting crops and markets in over 190 countries while complying with all regulations and imposed sanctions”.

Louis Dreyfus notedExternal link in its 2022 financial report that it suspended its operations in Russia following the invasion of Ukraine although they were later resumed “to the extent possible, aiming to meet commitments to and demand from customers, while complying with all applicable sanctions, laws and regulations.” In April, Reuters reportedExternal link that the company planned to stop exporting Russian grain as of July 2023, but a spokesperson declined to provide more details or comment on Iran when contacted by SWI.

Bunge, Cargill and Cosco did not reply to repeated requests from SWI for comment on whether exemptions from sanctions on humanitarian grounds allowed them to facilitate wheat transactions between Russia and Iran.

Payment issues hamper access to food

Even with humanitarian licenses, trading grain with Iran is fraught with difficulty. “Most people have no idea how hard it is to do business in one of the most sanctioned countries in the world,” Merzad Jamshidi, a member of the leadership council of the Mideast and Africa region of the International Association of Operative Millers, told SWI at the Geneva conference.

READ MORE: Commodities trading, Switzerland and the war

- Switzerland’s traders have had to adapt to the war. This means officially leaving Russia and finding new revenue models

- One year into the war, an FT report finds global energy traders Vitol and Gunvor, which both have their headquarters in Switzerland, are still major buyers of refined oil from Russia

- Switzerland imported unprecedented amounts of gold from Russia in February this year, according to a Swiss NGO that is campaigning for greater transparency in the gold sector. That’s despite sanctions imposed because of Russia’s war on Ukraine

A key issue is payment, because long-standing financial sanctions have cut off Iran’s access to the international banking system. “There are two issues when it comes to banking with Iran,” said Esfandyar Batmanghelidj, an economist and founder of the Bourse & Bazaar Foundation, a London-based think tank focused on the Middle East and Central Asia.

“First, very few Iranian banks maintain correspondent banking relationships with European banks, or any banks, for that matter,” he said. Most international banks are reluctant to engage with sanctioned countries, even on humanitarian goods. This makes it hard for Iranian wheat importers to find a banking channel to make payments to the exporter, Batmanghelidj said.

Second, there’s limited access to hard currency. “The challenge is that the Central Bank of Iran (CBI) has had most of its foreign reserves frozen and the oil money Iran used to fund its trade is no longer easily accessible,” said Batmanghelidj. The US restricted the CBI’s roleExternal link in humanitarian trade to crack down on money laundering and terrorism financing.

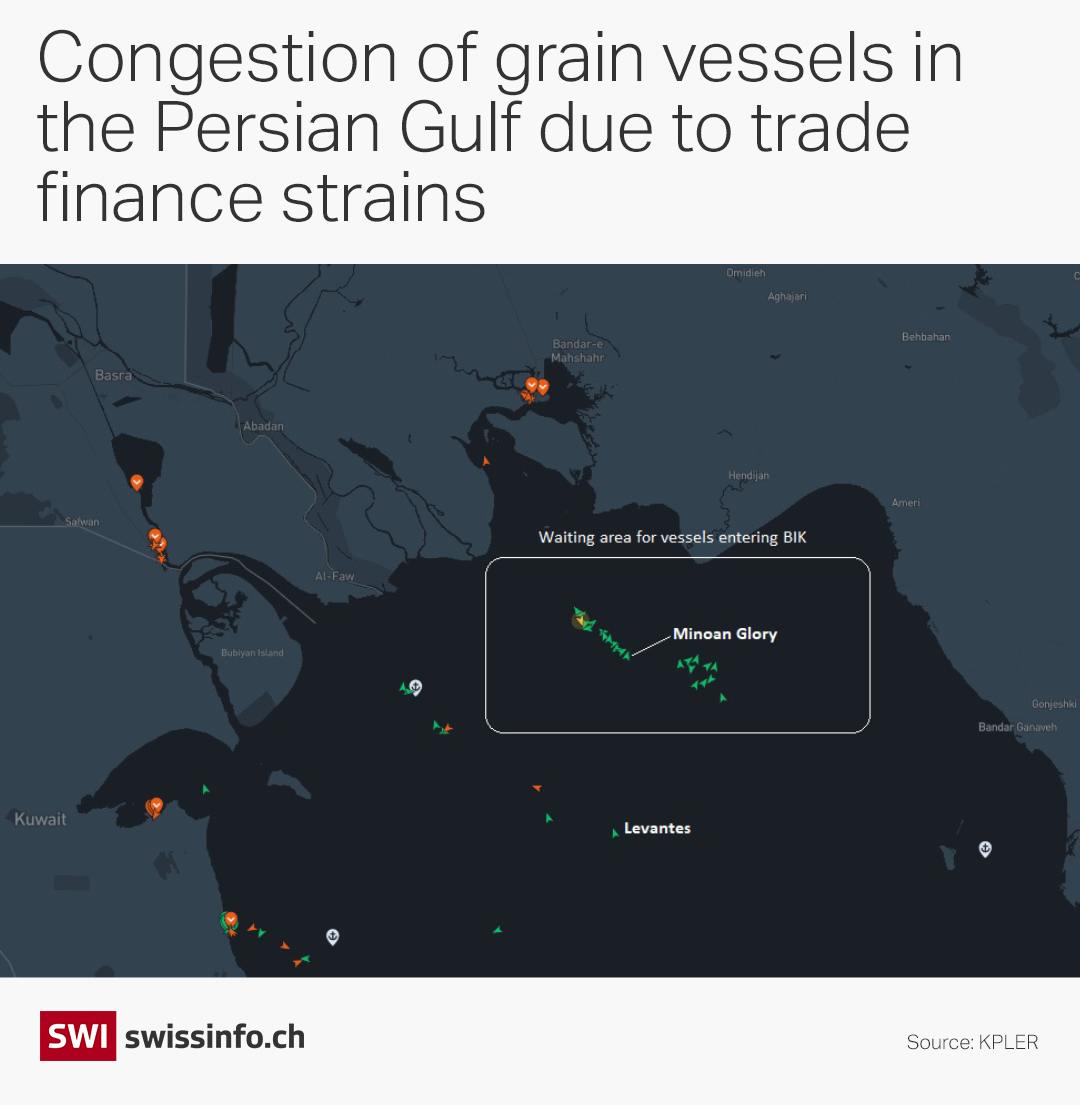

The CBI is also at the heart of a dysfunctional Iranian subsidy systemExternal link for essential goods like wheat that gives traders a preferential exchange rate allowing them to import at lower cost. But the central bank hasn’t managed to meet demand for hard currency in a timely manner, leaving grain carriers stuckExternal linkoutside Iranian portsExternal link for monthsExternal link awaiting payment for their cargoes (see map below).

Food pricesExternal linkhave skyrocketedExternal link in Iran over the past few years as the Iranian currency collapsed and the government cut subsidies. The UN’s Food and Agricultural Organization calculatedExternal link that the number of Iranians unable to afford a healthy diet soared to 17.1 million in 2020 – more than 20% of the population – from 9.6 million in 2017.

“Iran is a country where you don’t have an acute hunger crisis, but what the sanctions have done is create an environment where the affordability and availability of essential goods, including food, are not assured,” said Batmanghelidj.

More

Commodity trading in Switzerland, explained

New trade corridors

Wheat isn’t the only manifestation of growing links between Russia and Iran. Moscow has showed renewed interestExternal link in developing new trade routes. Diplomacy has been buzzing, with several meetings at presidential level in 2022 alone. Just one month into the invasion of Ukraine, Russia’s foreign minister pledged to work with Iran to circumvent international sanctions. The rapprochement has alarmed the USExternal link, whose top priority is to stop arms shipments between the two pariahs.

One major project is the International North-South Transport Corridor (INSTC), which aims to connect Russia to India through central Asia and Iran. The network of railroads, highways and shipping routes over and around the Caspian Sea is supposed to be more direct than the circuitous route through the North and Mediterranean seas and Suez Canal, significantly cutting freight transit time and costExternal link.

Although the project has been under discussion for more than 20 years, western sanctions have reinvigoratedExternal link Russia’s interest. A test batch of goods was shipped from St. Petersburg across the Caspian Sea to Mumbai in June 2022. Meanwhile, Iran has inched closerExternal link to the Eurasian Economic Union, a free trade bloc of several former Soviet states.

Moscow and Tehran have reportedly been workingExternal link on establishing direct financial channelsExternal link that bypass the western-dominated international system and Russia has become the largest investorExternal link in Iran – $2.76 billion, two-thirds of the country’s foreign direct investment in the year to March 2023, came from Russia, according to Iran’s finance minister.

There are limits to this Russian-Iranian nexus, however. The train lines of the INSTC are incomplete and while the shipping routes are operational, cargo capacity on the Caspian Sea is limited.

Batmanghelidj, the economist, doubts that intensified relations with Russia will be a game-changer for Iran. “They still have the banking constraints,” he said. “It is going to be very difficult for Russia and Iran to create a supply chain that compensates for the inability to buy essential commodities in the global market.”

And yet, the business executives attending the grain conference in Geneva saw plenty of opportunity for more regional trade. From an Iranian perspective, the grip of western markets and approaches is loosening.

Edited by Nerys Avery

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

![The four-metre-long painting "Sonntag der Bergbauern" [Sunday of the Mountain Farmers, 1923-24/26] had to be removed by a crane from the German Chancellery in Berlin for the exhibition in Bern.](https://www.swissinfo.ch/content/wp-content/uploads/sites/13/2025/12/01_Pressebild_KirchnerxKirchner.jpg?ver=a45b19f3)

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.