The encrypted phone vying to be BlackBerry’s heir

In Geneva, Steve Jobs’ former chess partner, a former US Navy Seal and a cryptographer run a company together. What they do is either a dangerous threat to the international security order or a vital safeguard for its future. Either way, the Dalai Lama is a client.

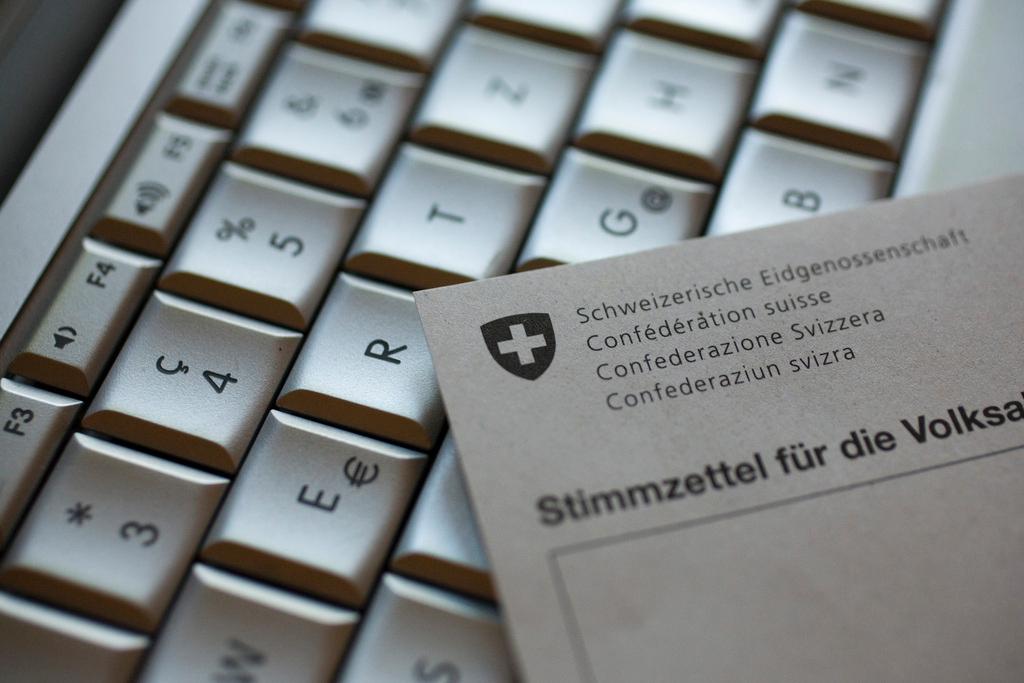

Silent Circle may not be a household name, but the phone the Swiss-based company has built – a modified Google Android handset impermeable to snooping thanks to its total encryption – is becoming a coveted device for the rich, powerful and secretive.

The first Blackphone, as it is known, sold out in weeks after being released last year. The second, released last month, is in equally high demand, even though users must put up with a more limited array of apps than they would be accustomed to in order to enjoy the security benefits.

“We’re replacing BlackBerry,” declares Mike Janke, one of the co-founders and an ex-US Navy commando. Mr Janke – who still carries the strapping frame of his former profession, now clothed in a neat company polo shirt – is an unlikely advocate of cutting edge cryptography.

Three years ago his claim to challenge a leading enterprise smartphone provider might have been laughable. But now 41 of the top 50 in the Fortune 500 ranking of US companies are clients, says Mr Janke, “and about 90 per cent of the US Senate”.

More

Financial Times

External linkEncryption in demand

Silent Circle is riding a global trend that is pitching companies, military forces and spies into the same digital battlefield at a time of massive technological upheaval. Businesses and individuals, corporate intellectual property and private lives are all mixed on the front lines of geopolitics. Encryption is spreading across the tech world as a result.

“The demand for it has to increase,” says Mr Janke. “Whenever I go away – to any hotel in the world, in South Africa, Argentina, Dubai, there are businessmen and women on their phones, on their laptops, using the hotel’s free WiFi. They have no idea how insecure what they are doing is.

“I remember watching one woman calling London from South Africa, talking about financial results. That conversation is crossing at least a dozen countries that are all sucking it out of the air.”

At Silent Circle, Mr Janke counts Phil Zimmermann, inventor of the global encryption gold standard PGP, among his co-founders. The other, the chess-playing Jon Callas, designed the security for Apple’s operating system.

Calls and messages from a Blackphone are end-to-end encrypted, meaning only the participants have access. Every other app and feature on the device is “locked down” – Google gave Silent Circle rare power to modify Android devices to do this – to prevent any unauthorised transmission of data.

Developing such a technology is not necessarily a comfortable place to be. In the wake of the Edward Snowden revelations, as communications and tech companies have rushed to embrace greater digital security, governments around the world have slammed those bringing encryption to the masses.

In November, Robert Hannigan, director of GCHQ, the UK’s electronic eavesdropping agency, accused companies embracing it of becoming the “command and control networks of choice” for terrorists. Intelligence agencies have warned repeatedly of the danger they face in “going dark” – losing access to the data that has made their fight against transnational terrorism, crime and espionage so successful of late.

Mr Janke, who has spent his career working with intelligence agencies, gives such arguments short shrift: “Law enforcement and government have a hundred other ways to find their guy or girl . . . Targets don’t necessarily use encryption for everything either. They might have a laptop. A home computer. A tablet. A credit card and a vehicle. All of those leave digital traces.”

By clamping down on encryption, Mr Janke argues, governments may make citizens far less secure by rushing through badly designed legislation, just as they were tempted to do when responding to the 1930s bank robbers Bonnie and Clyde. “That’s what we need to avoid here.”

A tough line to walk

At a time of growing digital insecurity – with countries such as China stealing vast amounts of corporate intellectual property through hacking – encryption offers much-needed defence.

The problem, though, is that the digital getaway vehicle Silent Circle potentially offers would-be wrongdoers is near-perfect too, if they use it correctly. For example, even if law enforcement agencies subpoenaed the company, it would be unable to disgorge clients’ communications because it cannot break into them itself.

Mr Janke says Silent Circle would happily deactivate clients’ phones if law enforcement agencies came to them with “life and death” situations. That, though, leaves plenty open. Would he, for example, authorise a client’s phone to be deactivated if an intelligence agency came to him with evidence it had ended up in Syria? “No.” Even if the agency said they had suspicions about its user? “No.”

“We’re trying to be completely neutral, we don’t want to be radical on either side of this debate,” he says.

It is a tough line to walk. As Mr Janke is also keen to point out, though, Silent Circle is far from being the enemy of western spycraft. It supplies the FBI. In the UK, a team of former SAS commandos is selling the Blackphone to British agents. “It’s close to 37 countries who are purchasers of our software . . . On the policy side, there’s criticism, but on the operational side, they’re buying our stuff like hot cakes.”

Ultimately, says Mr Janke, it will not be governments that inhibit the spread of encrypted devices such as the Blackphone but Facebook and other big tech companies. “People like to talk about the NSA, China, Russia, GCHQ, but let me tell you the largest purveyors of data theft out there are the technology firms themselves. Every free app is sucking globs of data off your phone hourly and they do atrocious things.”

Encryption blocks this business model. “The backlash is going to come from the big data firms. That is the new war – the new gold coming out of the ground isn’t oil. It’s your data.”

Fears of ‘going dark’

Since Edward Snowden stole and leaked thousands of secret documents exposing electronic eavesdropping activities, US spymasters and their peers have repeatedly warned they are “going dark”. The betrayal, they say, has been a bonanza for terrorists and hostile states. In laying bare the capabilities of the National Security Agency and Britain’s GCHQ, it has allowed enemies to better protect themselves from their snooping.

It is hard for the agencies to substantiate such claims without revealing even more about themselves. But there is plenty of evidence to suggest their fears are more than just scaremongering. Isis, the jihadi terror group that has seized a swath of territory in Iraq and Syria, is perhaps the prime example. It has disabled the GSM network in sensitive areas of its territory to prevent geolocation of mobile signals. Wireless operation is banned in its stronghold Raqqa. Documents circulated among its fighters show how to scrub data from mobile communications. And its leadership practises scrupulous digital hygiene. Many never use phones or computers.

Where Isis’s commanders do use the internet, it is in line with Mr Snowden’s precepts: they encrypt and anonymise. Undoubtedly, some such activity would be taking place regardless of whether the Snowden leaks had occurred or not, but what the NSA and GCHQ fear most is its spread. The more ubiquitous and cheap it becomes to encrypt communications as a matter of course, they point out, the harder it becomes to conduct any kind of signals intelligence work in the fight against terrorism.

Copyright The Financial Times Limited 2015

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.