Swiss reflect passion behind Olympic nod

To non-climbers, it can seem counter-intuitive for someone to want to scale indoor walls when there are Swiss Alps and sunshine beckoning nearby.

But most young people are learning to climb at indoor rock gyms, easily reached in cities and impervious to bad weather. This has begun shaping the future of the sport. And now that climbing is being addedExternal link to the Tokyo 2020 Olympics, the sport stands to become even more popular, competitive and urban.

Switzerland’s highest indoor climbing wall, O’BlocExternal link, opened last year on the outskirts of the Swiss capital Bern, and its carefully calculated equilibrium between indoors high-tech chic and outdoors-leaning aesthetics speaks volumes about where the sport is headed.

Climbers pay for the steep allure of plastic overhanging holds and protective bolts carefully designed by the gym’s route setters, but there also are huge windows and doors that allow the natural light to stream through in an almost meditative view onto the green pastures of a neighbor’s working farm.

“It’s just a different way of thinking,” said Sascha LehmannExternal link, who won a national youth championship this summer, about learning to climb in gyms instead of in the mountains.

On Saturday, he was among the winners in another national competition, held in a climbing gym at Uster, near Zurich, as part of the Bächli Swiss Climbing CupExternal link series.

Lehmann showed up at the O’Bloc gym in Ostermundigen – birthplace of actress Ursula Andress, Switzerland’s most illustrious export to Hollywood – in casual street clothes that can double as climbing attire. The 18-year-old from Burgdorf, in the Swiss canton of Bern, said he appreciates the convenience of climbing indoors most days of the weeks.

“You don’t have weather in the climbing gym – all these different things which you have in mountaineering,” said Lehmann, who has a good chance at making it to the Tokyo 2020 Olympic Games. “It’s quite easy to enter the sport.”

Climbing beyond mountains

In countries with rich mountaineering histories, the swelling ranks of alpine clubs reflect an interest in a variety of mountain sports – they are enjoying a renaissance in membership based on broadening their appeal.

The Swiss Alpine ClubExternal link has grown to 150,000 members – about one of every 50 people living in Switzerland. It maintains a broad network of huts, similar to the German and Austrian clubs, which have 1 million and 500,000 members, respectively. The American Alpine ClubExternal link, which in decades past catered only to elite alpinists and now maintains a few huts and campgrounds at premier climbing areas, has risen to more than 16,000.

The current trends in climbing, however, mean that fewer people are likely to automatically equate the word “climbing” with an “alpine” activity. The International Olympic Committee’s decision in August to add climbing to the program in 2020 may be seen someday as an important turning point.

“We expect sport climbing will receive more support worldwide, which should only be good for our athletes,” Joseph Robinson, a spokesman for the International Federation of Sport ClimbingExternal link (IFSC), told swissinfo.ch.

A global phenomenon

There are now 25 million people – about one of every 300 people on the planet – climbing regularly around the world, according to IFSC figures.

That includes thousands of people in Switzerland and the United States. The IFSC now has 87 member federations on five continents, almost half of them in Europe – a 25% increase from a decade ago.

“Probably the sport will get even more popular. Probably there will be a bit more money for climbers,” Lehmann said. “Of course, I was very excited – it was a big honor for us as sport climbers. When it gets Olympic, it says that it’s a sport which a lot of people do around the world.”

More

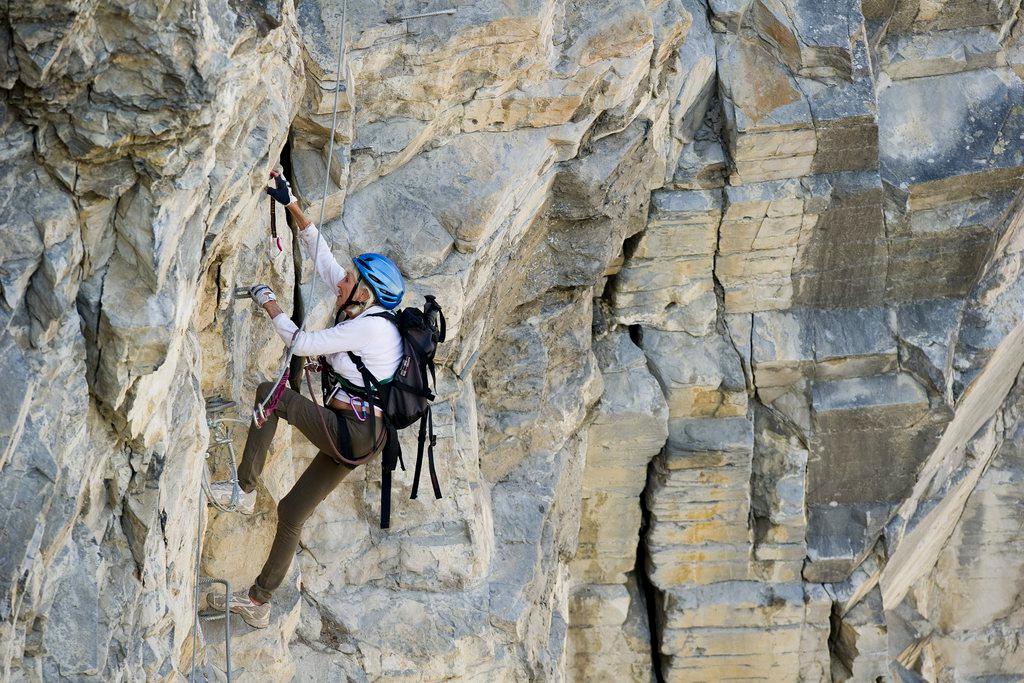

Passionate about pushing the limits – indoors or out

Making a living

Lehmann, whose father competed as a gymnast in the Los Angeles 1984 Olympic Games, has already devoted nearly a decade of his young life to sport climbing and risen in the rankings. After growing up in a family that long enjoyed outings together, he now hopes the Olympic attention might bring more career possibilities.

“One good point is that it would probably be possible to live as a sport climber, to do it as a professional,” Lehmann said. “Today, it’s not really possible, there are just a few athletes which manage to live as professionals.”

It takes years of physical and mental training to be a good climber. At its essence, climbing is about a state of grace, a sense of body awareness, and a mental challenge – you have to problem solve. A climber learns how to think with his muscles, instantly recognizing which body positions will work.

After many of these young climbers learn how to move, and how to use ropes and harnesses to secure themselves, they may not aspire to move on to bigger things, like the Alps. More and more they prefer sticking to the gyms and crags, and to training for sport or for competitions.

Urbanisation

In their decisionExternal link to add climbing in Tokyo, the International Olympic Committee described the importance of two trends. One is to bring the Games to more young people. The other is to reflect the growing urbanisation of sport.

Lehmann will be 22 when the Tokyo Games are held. Only 40 men and women will be chosen to compete. Already a Swiss champion, Lehmann might have to be a European champion to claim one of only 20 Olympic spots for men. There also will be 20 spots for women.

To win, he will have to master three different styles of climbing. The one he already excels at is lead, or sport climbing. For that, you move up, clipping a rope at your waist through bolts as you go. If you fall, you lose. The second is speed – a race to the top protected by a rope overhead. The third is bouldering. The routes are only a few metres high. The winner gets up in as few tries as possible.

Mishmash of styles

One prominent US sport climber, Sasha DiGiulianExternal link, hopes to be one of the 20 women selected to compete in Tokyo. In a recent essay, she described what it felt like to gain the chance to attain her childhood dream of competing at the Olympic level – and how the growth in the sport has helped.

“At its core, climbing is an outdoor sport, but it’s evolving. In the past five years, climbing has shown incredible growth and climbing gym memberships have spiked,” she wrote for an article published in AugustExternal link in Outside Magazine. “Having the opportunity to be part of the largest world stage, the Olympics, makes sense for the progression of competitive climbing.”

DiGiulian, however, questioned whether the International Olympic Committee truly understood the nature of climbing. She described the way it might try to condense the three distinct styles of climbing – lead (sport), speed and bouldering – as “a fabricated, artificial version of competitive climbing”.

Growth of gyms

The rise of the sport is also good news for a seasoned climber, mountain guide and coach like Christian Tschudi, whose passion led him to open O’Bloc, which has walls that go up to 19.5 metres, making it the highest among a growing lot of dozens of Swiss high-quality indoor climbing facilities. Bern’s other climbing gym, MagnetExternal link, with walls up to 14 metres high, has already played a big role in the rise of climbing since its opening in 1993.

“We have had steady growth since the last 20 years in climbing. We’re not a boom sport,” said Tschudi, who is helping to coach Lehmann. “It’s a community sport, and that’s also very nice. It’s a little family also in Bern here, everybody knows each other.”

Many of these young climbers, after they learn how to move, and how to use ropes and harnesses to secure themselves, no longer aspire to move on to climbing in the Alps. More and more they prefer sticking to the gyms and crags, and to training for sport or for competitions. “It’s getting to be really a popular urban sport. That’s why in every big city in Switzerland you have climbing gyms,” said Tschudi.

“I think you will always have the two ways: There will be people that do only the gym climbing, and there will always be the people that go and climb outdoors, and it’s their life, their passion,” he said. “I think for the sport it’s no problem. There can be these two parallel worlds. Everybody learns from each other.”

A booming (mostly) indoor discipline

Sport climbers train in three disciplines: lead climbing; bouldering; and speed climbing, while tied to a rope above.

As of last year, the IFSC counted 2,000 licensed athletes among its ranks, including more than 700 women, representing 62 countries. Their median age was 19, though most devotees keep on climbing until the age of 60 or more.

In 2016, the IFSC is slated to hold more than 20 international climbing competitions that are live webcast and expected to draw tens of thousands of spectators.

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.