In Switzerland, look before you leap

This summer’s regular media coverage of BASE jumping and mountaineering accidents in Switzerland begs the question: why aren’t “extreme” sports more closely regulated? swissinfo.ch examines the Swiss emphasis on taking personal responsibility for one’s actions and their consequences.

According to the Swiss Council for Accident Prevention, about 11,000 Swiss residents suffer accidents requiring medical attention while doing mountain sports such as hiking, climbing, skiing and snowboarding each year.

But if something goes wrong during a BASE jump – a parachute-aided leap off a fixed object such as a mountain, building, antenna or bridge – there isn’t much anyone can do to prevent a fatal impact.

“In other sports you also get injuries, but if we mess up, in most cases it is deadly,” says Michael Schwery, president of the Swiss BASE Association (SBA).

Despite the risk – or perhaps because of it – BASE jumping has gained a devoted following since its founding in the early 1980s. Laws regulating the sport vary widely between countries, sending many enthusiasts to Switzerland where the mountains are high and the rules are few.

BASE jumpers in Switzerland, for example, must steer clear of “no-fly” zones closed to planes and helicopters, and are legally required to carry a skydiving license and third-party insurance. Otherwise, anything goes – no bans in national or regional parks as in the United States and Australia, and no lengthy permit application procedures and safety requirements as in Germany.

“I think it is a cultural thing,” says Schwery of the laissez-faire attitude. “Switzerland is country that gives a lot of personal freedom; a lot of things are left to personal judgement.”

Alpine obsession

Swiss mountain sports culture is interwoven with the nation’s history of adventure tourism. Starting in the 1850s, before the invention of Gore-Tex and GPS, mountaineering was considered an “extreme” sport. British climbers flocked to Switzerland to test their skill – and their fate – with the hope of winning the respect of their countrymen. Their journeys often relied heavily on the expertise of Swiss guides, thus complicating the question of who took credit for a successful climb, and who was to blame for a doomed one.

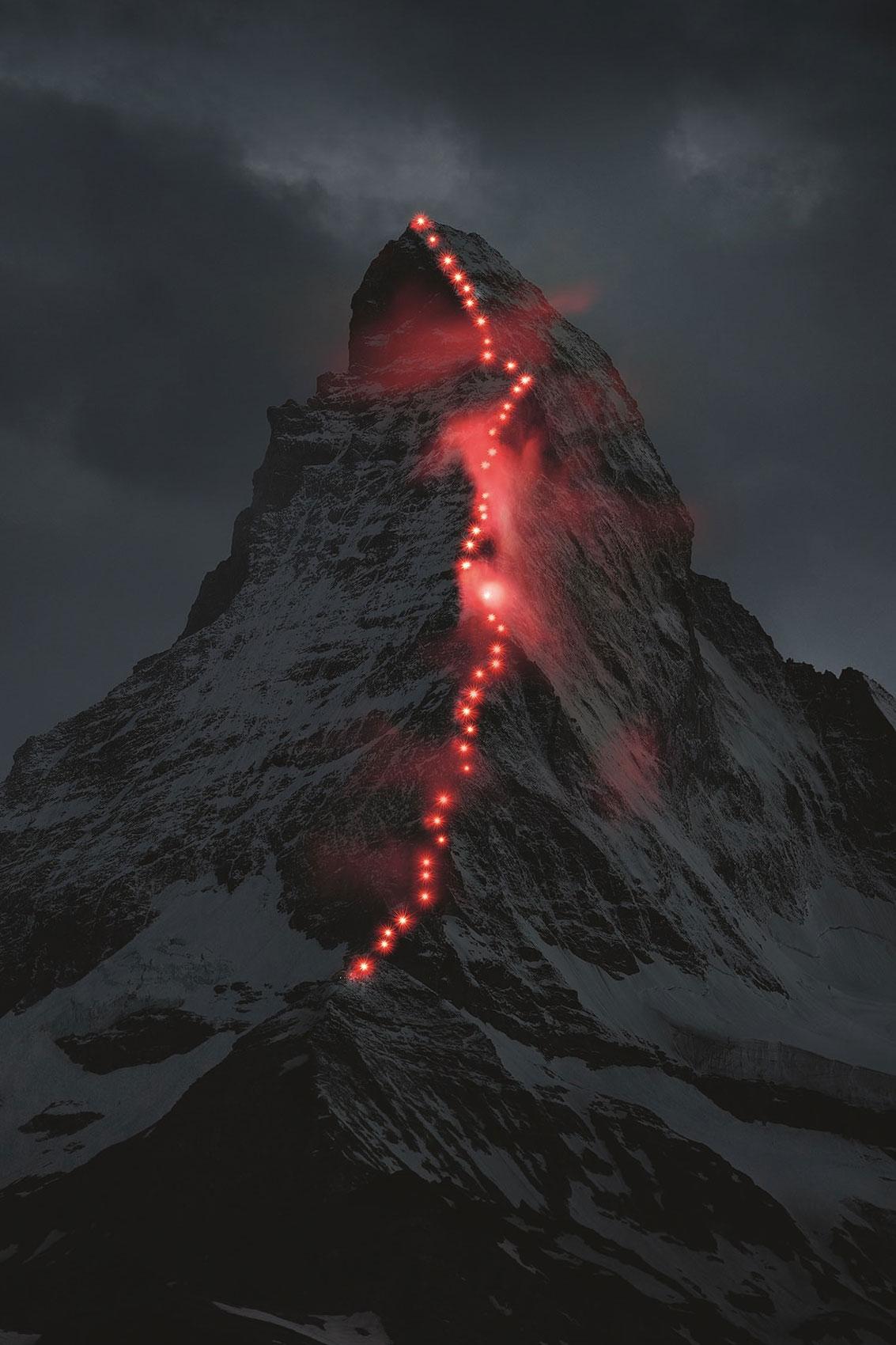

In 1865, four mountaineers – three English and one French – died during the first ascent of the Matterhorn, while English expedition leader Edward Whymper and Swiss guides Peter Taugwalder and son survived. The series of events leading up to the tragedy were unclear, and cast suspicion on the actions of the three survivors in one of the most famous accidents in mountaineering history. Following the tragedy on the Matterhorn, Queen Victoria considered a ban on mountaineering for British citizens, but ultimately decided against it. Many Englishmen were inspired by the story of Whymper and his fellow climbers and so, in the absence of a ban, interest in scaling Swiss mountains intensified.

Proceed at your own risk

Today’s adventure sports bring many to Switzerland not only for the challenging mountains and stunning landscapes, but also for the relative freedom from legal restrictions compared to other countries.

“Swiss people don’t like orders that tell them what they cannot do in their spare time,” says Bruno Hasler, training director of the Swiss Alpine Club.

Hasler told swissinfo.ch that Swiss law is quite liberal when it comes to mountain sports, “as long as you [proceed] at your own risk, and you don’t risk the lives of other people”.

Policemen may patrol some ski slopes in France and Italy, for example, turning skiers away from the lifts if conditions are judged to be too risky.

“This kind of thing has never happened Switzerland,” says Hasler. “[The authorities] just say ‘OK, we recommend that you don’t go there’, but there will never be a policeman stopping you – it is your own responsibility.”

Laying down the law

The Swiss reliance on personal responsibility is codified to some degree by the Bern-based International Climbing and Mountaineering FederationExternal link: “[Mountaineers and climbers] pursue this activity at their own responsibility and are accountable for their own safety. The individual’s actions should not endanger those around them nor the environment.”

But this isn’t to say that Switzerland hasn’t toyed with the idea of stricter regulations in the past. In July of 1936, four men died attempting to scale the north face of the Eiger after a harrowing 48-hour series of injuries and accidents. The canton of Bern banned climbing on the Eiger’s north face shortly after the disaster…only to have the ban overturned four months later when it became clear that it wasn’t the least bit effective at keeping mountaineers away.

Aside from the problem of enforcement, some believe that prohibitions on mountain sports can even increase the risk of injury or death. Many BASE jumpers argue that when access to mountaintops, cliffs, and other prized jump sites is restricted, BASE jumpers tend to have even more accidents trying to circumvent those restrictions.

“People [BASE jump illegally] in the early morning or late at night when the light conditions are bad, and when they are stressed about getting caught, and they have to rush,” explains Schwery.

Information versus regulation

For the Swiss, providing information is your best bet when it comes to preventing disaster: what people choose to do with that information is up to them.

Hasler says that situations don’t often arise in which an individual causes harm to others.

“You only have a problem when you are responsible for an accident and you hurt other people… If you do [off-piste skiing] and cause an avalanche that goes over the prepared ski slopes, then you have a severe problem. But this is quite rare.”

Indeed, the Council for Accident Prevention estimates that when it comes to snow sports, the injured individual is the only person involved in 90% of accidents.

For both snow sports and mountaineering, the council places the responsibility for safety firmly with the adventurer, citing excessive speed, lack of expertise and preparation, and even alcohol intoxication as the most common reasons for accidents, with “extrinsic risk factors such as natural dangers or infrastructure play[ing] a subordinate role”.

In addition to technical skills like rope-handling, the council recommends advance communication and education on perception, planning, judgement and decision-making for all individuals wishing to participate in mountain sports – winter or summer.

Schwery says that the SBA also focuses primarily on providing information and safety education. He adds that no matter what rules are established to protect people from the risks of extreme mountain sports, people are likely to find a way around those rules.

“I think information is the best you can do,” he says. If you make regulations, there is a very good chance they will be broken.”

What is BASE jumping?

BASE jumping is named for the four types of fixed objects jumpers can use: Building, Antenna, Span, and Earth. After the initial leap, BASE jumpers soar downward for a short period of time – usually well under a minute – before deploying a pilot chute, which in turn deploys a the main parachute, or canopy. A wingsuit, or squirrel suit, is a special piece of equipment with webbing between the legs, and between the arms and the sides that jumpers can wear to prolong the flight to about 1-1.5 minutes, as opposed to about 7-10 seconds with a regular suit. It takes another 1-2 minutes to land after the chute has been deployed. While a skydive is typically made out of a plane at 4,000 metres, an average BASE jump is made from a height of 600-800 metres, leaving less time to negotiate parachute deployment or to correct the flight trajectory.

On average, about six people die BASE jumping in Switzerland each year.

Michael ‘Michi’ Schwery’s flight

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.