Swiss chips not vital to Lancet drone production: Russia military expert

Lancet drones prized by the Russian army are a headache for Ukraine. They are also equipped with Swiss-made components. SWI swissinfo.ch speaks to Russian military expert Valery Shiryayev to understand why they are so effective and what would happen if Russia no longer had access to Swiss parts.

Shiryayev also serves as deputy director of the independent Russian newspaper Novaya Gazeta.

SWI swissinfo.ch: What is the role of unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) also known as drones in the war in Ukraine?

Valery Shiryayev: This system of warfare emerged completely unexpectedly for the United States in the war, but not at all for Russia. This new class of weapons, previously considered marginal, is suddenly playing a huge role. The simplest drones can reach speeds of 100-120km/h. They are flown directly by an operator and can reach five kilometres into the enemy’s territory. The most significant damage to the front lines of the troops in the war in Ukraine has been inflicted by such devices and not by super-modern, expensive, and complex machines that Chinese, Korean, and other military forces have been investing in.

SWI: So expensive doesn’t necessarily mean good?

V.S.: The relationship between quality and price began to change during the American war in Iraq; United States army contractors on the ground were asked to destroy Iraqi infrastructure and bombs at a minimum cost. They started using $20 (CHF18) toys bought in supermarkets to which they attached a remote-controlled engine, and a GoPro camera with tape. This resulted in a device ready to approach an object and safely inspect it from all sides. After that, they disconnected the camera and attached an initiating explosive charge instead. The toy approached the target once more; it exploded, and that’s it. It’s a disposable, consumable item that costs hundreds or thousands of times less than a complex device that the US Army originally provided to their contractors. For the military, the main indicator of a weapon is its effectiveness, not its cost. I calculated that the components which make up a Shahed 136 Iranian drone cost €1,500 (CHF1,450); that’s without the cost of the explosives.

More

Russia’s killer drones still boast Swiss components. How come?

SWI: Simple technology is also used in the war in Ukraine.

V.S.: The war in Ukraine proves that simplicity is enough. Both Russia and Ukraine use drones assembled from parts that they buy in bulk for cheap.

SWI: Are these not military equipment?

V.S.: These are civilian equipment. Ukrainians make drones like the UJ-22, known as Bobber, using readily available components from supermarkets or local markets. The Taliban were the first to use these against American coalition forces; every commander of a small Taliban unit had a cheap Chinese motorcycle and had a Chinese drone with a camera in their backpack. The drone’s flight range in the mountains was no less than 2.5km. So, the device could fly over a pass and conduct reconnaissance. In a way, they were better equipped than the US army at the time.

SWI: So, an efficient drone is just slightly more expensive than the latest iPhone?

V.S.: Yes. The American army claim that the cost of the Shaheed drone is $30,000-40,000. I think that this price is greatly inflated. It’s much cheaper in reality. When the Americans disassembled it, they found a Texas Instrument TMS320 control chip inside. They were shocked, and this fact caused a stir in Western media, with calls to ban its export to Iran, China, and especially Russia. The problem is that this chip was mainly manufactured in 1983, and the last modification was made in 1992. Since then, more than 20 million of these processors have been produced worldwide. Thirty years later, this chip is used in toys, video game consoles, in industrial elevators – its applications are countless. Five Russian plants now produce these chips inside Russia, any roadside workshop in China can produce it.

SWI: it possible to control the production of drones by Russia?

V.S.: Prohibiting the export of Texas Instruments is pointless. This chip, which is now practically worthless, controls all the onboard systems during the flight of the Shaheed drone. It plans the route, assesses the approach to the target, maintains communication, controls satellite navigation, and the routed map. It’s used in toys, video game consoles, and in industrial elevators — its applications are countless. Trying to control their movement around the globe is impossible.

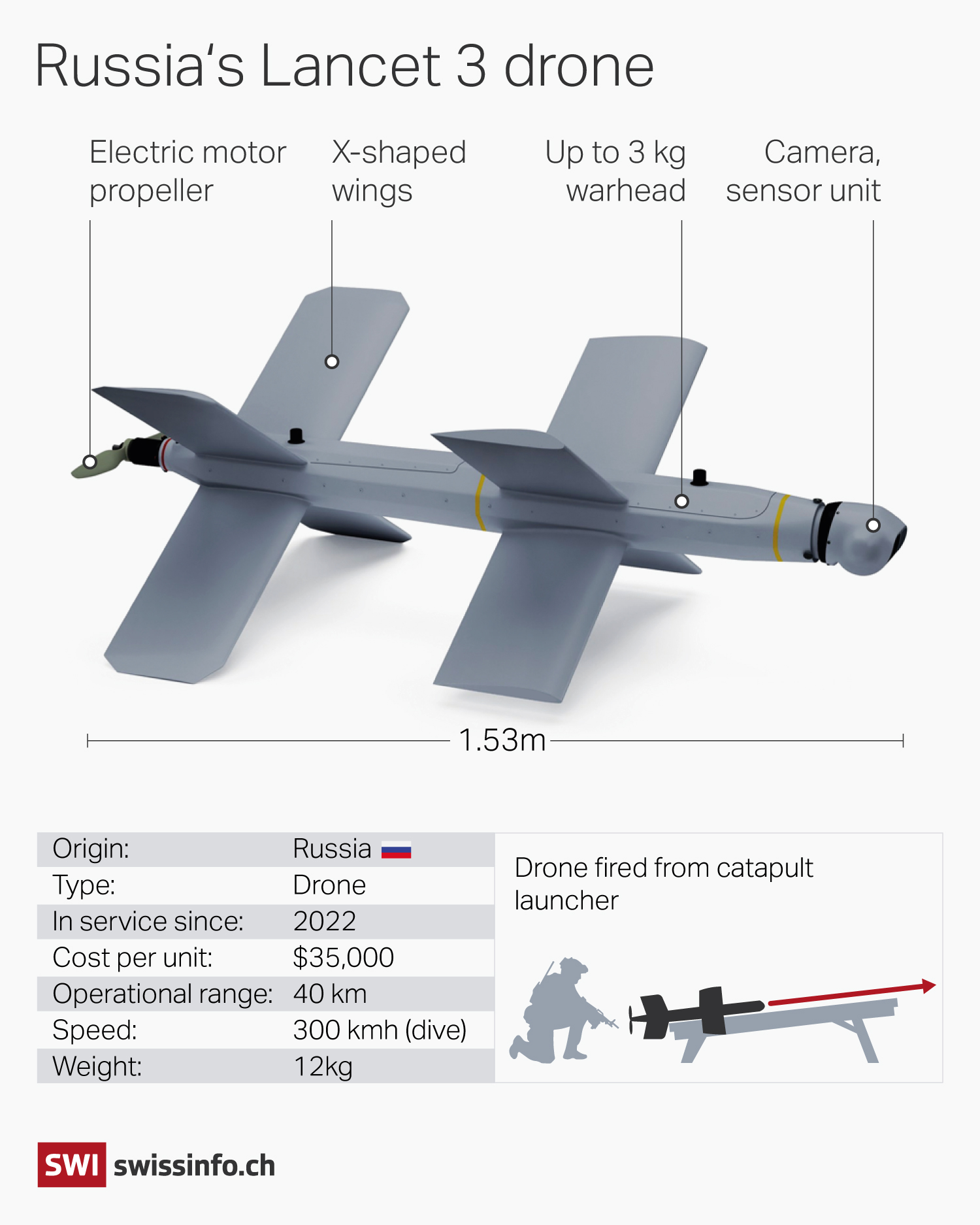

SWI: The Ukrainian military says the Lancet drone is one of their main problems on the battlefield. These are Russian-produced drones but equipped with components from Swiss companies such as STMicroelectronics and u-blox. What can be done to avoid Swiss components ending up in Russian drones?

V.S.: I believe that all these discussions by the Ukrainian side about what needs to be done stem from a sense of helplessness. There’s not much that can be done. The technology used in these drones is beyond the realm of military control. The chip used in Lancet is readily available on the market; it can be ordered for $250 on the [Chinese] e-commerce website Alibaba. And it isn’t classified as a military product.

More

Russia’s killer drones still boast Swiss components. How come?

SWI: Why does the Ukrainian army consider the Lancet as one of their main threats?

V.S: What sets the Lancet apart from the devices competing with it in global markets, such as the Switchblade 600? It’s essentially the same in terms of tactical and technical characteristics, the Switchblade has even a more advanced warhead than the Lancet. The main difference is that the Lancet, as its manufacturer openly states, does not rely on satellite control which can easily be jammed in wartime. Drones can be misled and prevented from reaching their targets using a technique called “spoofing”. The Russian army have simplified and complicated things at the same time. Maps are pre-loaded into the device. When the Lancet flies over the surface, its camera constantly matches the presence of various reference points on the ground with the map. It navigates based on the terrain. In simpler terms, it’s like what a person does when flying on a plane. You could blow up all the satellites, and it wouldn’t make a difference to the Lancet.

In this sense, credit must be given to the manufacturers at Zala Aero and their experts and engineers who took an unconventional path and achieved this effect. According to satellite imagery and video databases of confirmed Lancet attacks, there have been approximately 700 such attacks to date. Roughly one-third of these attacks have resulted in complete target destruction, and about half in partial target damage. That’s an 80% effectiveness rate is considered normal, even good.

These same databases show that that the effectiveness of the Switchblade 600 is almost zero. They are either getting jammed by Russia’s electronic warfare or have some structural flaws. The most crucial thing is that it doesn’t inflict the damage the Russia’s army needs.

SWI: What other differences set the Lancet apart from its American competitor?

V.S.: The Lancet is constantly evolving. It’s not the same weapon as it was a year ago. The engineers keep adding new features and improvements. The Lancet is a small drone that flies at relatively high altitudes. They are compact, stealthy and agile; hardly anyone can shoot them down. The Lancet operates in pairs with a reconnaissance drone that identifies the target. The Lancet is then deployed to destroy the identified targets. This combination of scout and strike is a fundamental principle in this warfare.

The Russian army has now deployed an upgraded Lancet fired from a portable. The drones communicate with each other in the air using radio communication to form a swarm of flying drones. They exchange information about what they see and which targets each one will destroy. For example, a swarm takes off and, while they fly, they decide which drone will destroy which carriage.

The Lancet is setting the example for what future American warfare will look like. The US will catch up very quickly.

SWI: Can Lancet drones function without Swiss components?

V.S.: It will be very difficult for a company to track all their chips and impose sanctions on their resale, but not impossible. If this happens these chips will simply be replaced within the concept of “open architecture”. What this means is that individual components of the device possess certain properties. All these components are interconnected with special software. In that software an engineer uploads the information that they have replaced a chip with a another. The software sees no problem and continues to function.

It’s like trying to fit a Mercedes driveshaft into a Volkswagen; it won’t work. But replacing one component with another within an open architecture is no problem.

So if Russia has no access to the ST Microelectronic chip for instance, it will just replace it with another Swiss chip. Production of Lancets doesn’t require precision machinery like those used, for instance, in metal processing or what’s procured primarily for shipbuilding and aviation. I don’t know the quantities they’ll be able to produce though, that’s genuinely a military secret.

The software used by Zala, the company which produces the Lancet, plays an equally significant role as the components themselves. The software is unique. And there hasn’t been a single proven case of someone capturing a Lancet intact to the extent that they could crack open the software and see how it works. It’s designed in a way that the software instantly becomes useless.

Edited by Virginie Mangin/ds

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.