Swiss army uses drone technology. Should we worry?

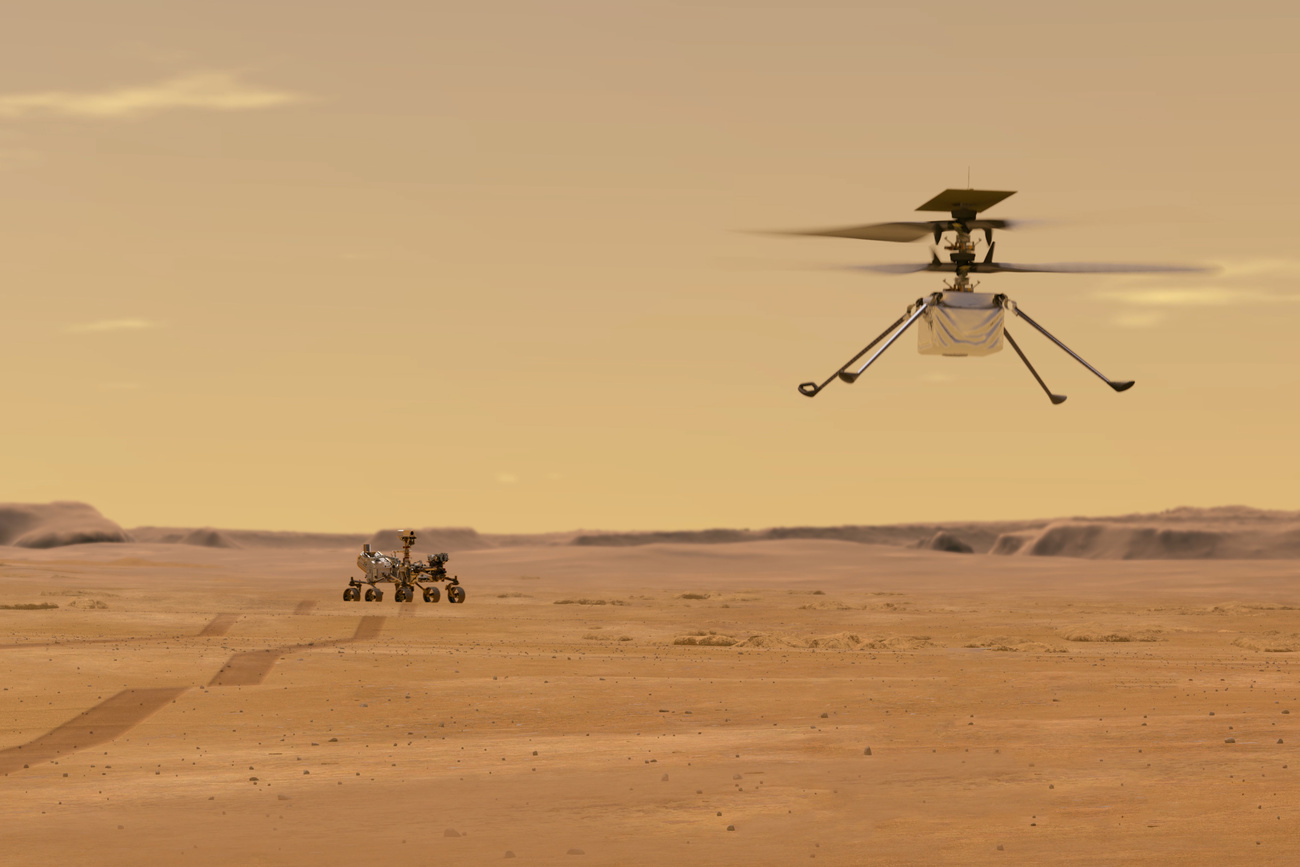

The same small drones that search for missing people and transport medicines are increasingly being used on the battlefield. Swiss researchers leading the global development of drones and other robot technologies are undeterred by the possible wartime applications of their discoveries.

Small commercial drones are playing a key role in the war between Russia and Ukraine. Anyone can buy and fly them without special training, and at a cost of CHF2,000 ($2,000), they are relatively cheap. They can fly over occupied territories and capture atrocities on camera, monitor every step of approaching troops and guide mortars to their exact positions.

These are mostly quadcopters (drones with four rotors) that weigh less than a kilogram and are equipped with high-resolution cameras and a powerful zoom lens. The Ukrainian defence forces have purchased thousandsExternal link of them since the beginning of the war, and the technology has given them an unexpected advantage. The Russian army has also been using them.

Most of those drones are manufactured by the Chinese company DJI, which has repeatedly stated that its products are not made for military purposes and temporarily suspended their sale in Ukraine and Russia.

But when it comes to the development of next-generation technology for four-rotor drones, Switzerland leads the way. Its drone industry ranks first globallyExternal link in market size per capita and is expected to grow to from CHF521 million in 2021 to CHF879 million in the next five years pulled by exports mainly to Europe and the United States. With their universities and Federal Institutes of Technology, Zurich and Lausanne have become international hubs for drone technology research.

Hovering between civil and military use

Zurich-based Professor Davide Scaramuzza has spent the last thirteen years developing small autonomous drones. His group is a world pioneer in their design.

The drones can explore forests, caves, collapsed buildings and radioactive zones or fly over disaster-struck areas in search of survivors.

Using vision sensors, they can map areas that are difficult for humans to reach – an application that is increasingly attracting military interest. In 2021 the Libyan army used autonomous quadcopter drones equipped with explosives to search for and attack human targets. The incident was reported by the United NationsExternal link.

Scaramuzza is not surprised that the results of his group’s finding may have military applications. “All robotics can be used for defence but also the other way around,” he points out, citing the fact that many tools that have improved our daily lives, such as the Internet and GPS, originated from military research. Even the invention of the microwave oven can be traced back to a component used in military radar during the Second World War.

Scaramuzza received funding from the United States’ Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency, or DARPA, to develop his state-of-the-art drones. He sees such grants as “innovation accelerators” because without them, technological advances would still happen, but at a slower pace. Scaramuzza clarifies that the DARPA-funded projects, which ran from 2015-2018, were not classified and therefore did not involve the provision of military software. “The results are transparent and in the public domain. The world stands to gain from them,” he says.

But Scientists for Global Responsibility (SGR), a UK-based organisation that promotes ethics in science and technology, argues that military-civilian technology exchanges are in fact mostly a one-way street today, with the military benefiting much more than the other way round. “It takes a lot of work to convert a military technology for civilian use,” says Stuart Parkinson, an environmental scientist and Executive Director of SGR.

‘Any technology can be misused’

DARPA funds basic and applied researchExternal link projects with no immediate military applications to gain insight into state-of-the-art, financially risky but potentially revolutionary ideas. In 2021, basic research accounted for 15%External link of DARPA funding and applied research for 39%. However, such funding initiatives allow DARPA to secure a long-term advantage when it comes to turning research findings into concrete products. For example, the agency is already using driverless car technologies, which were originally developed through research competitionsExternal link, to advance military vehicles.

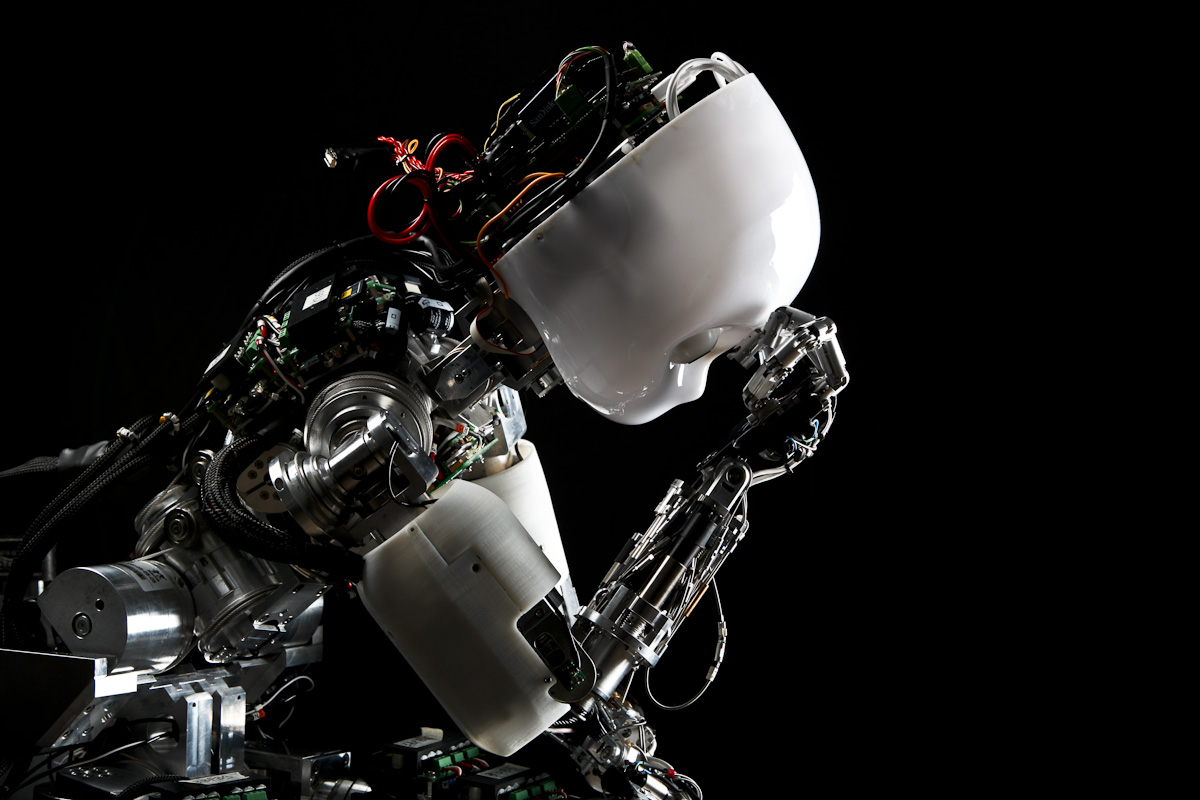

“In principle, any technology can be misused,” says Marco Hutter, who is a professor of robotics at the federal technology institute ETH Zurich. His research group developed a four-legged robot called ANYmal, designed for autonomous robotic inspection and for search and rescue in disaster areas. Several of these robots were deployed during a multi-year DARPA-funded robotics competition that Hutter and his group won in 2021, taking home part of the price money of $2 million.

The dog-robots have been commercialised by ANYboticsExternal link, an ETH Zurich spin-off to which Hutter contributed. While ANYbotics prohibits armed military use of their machines by contract, the US-based company Ghost Robotics launched a similar robot armed with a sniper rifleExternal link last year.

Prevent not cure

The dual use – and potential misuse – of new technologies is difficult to prevent, in part because there are no clear rules limiting their development and export. While there are various international organisations and United Nations bodies inspecting and prohibiting atomic and chemical weapons, this is not the case for innovations in the digital space, as they are less tangible.

And competition among countries’ militaries to exploit new technologies is fierce. This makes it difficult to implement and make binding international treaties that restrict the proliferation of certain weapons and set guidelines for researchers in emerging fields such as robotics and AI, according to SGR. Switzerland, for example, is reluctantExternal link to support the campaign for a treaty banning killer robots, stating that this may lead to the prohibition of systems that could prove useful to civilians.

Because legislation lags behind technological progress, the scientific community has started to “self-regulate,” says Ning WangExternal link,External link a political scientist and expert in the ethics of emerging technologies at the University of Zurich. She cites the 1975 Asilomar conference, which led to ethical and regulatory debates on the recombinant DNA technology, as an example. The meeting, which was established by scientists, set long-term guidelines for experiments that could endanger public health, but did not create binding standards..

More

The ethics of artificial intelligence

There is also an underlying issue with the way academia works: researchers are required to publish their work in journals to make it widely accessible, but once their findings are published, they no longer have control over how they are used to create actual products.

Instead of disseminating its know-how, Switzerland should focus on translating its research findings into products, according to Disc, a consortium of private companies promoting Swiss defence innovation. Its director, Hanspeter Faeh, argues that this would allow the country to keep the application of technologies under control and prevent knowledge from being misused or “exported” to states that do not respect human rights.

The risks of the trade

But regulating modern innovations and turning them into products is complicated by the fact that they are made up of countless technologies. Drones, for example, are not just made of rotors, propellers and cameras. They employ sophisticated algorithms to recognise roads or people and achieve a certain autonomy.

Jürgen Schmidhuber, considered by many to be the “father of modern artificial intelligence”, is aware that the machine-learning methods developed by his research group in Lugano and Munich have been used not only by Google and Facebook, but also by the military to activate drones and enable them to hit precise and selected targets. But this doesn’t keep him up at night.

“Ninety-five per cent of the applications serve to improve people’s lives,” he says. His discoveries have advanced the field of healthcare by enabling the detection of tumours, through imaging and machine translation.

“However, that remaining five per cent of military applications aim to do the exact opposite and that is to succeed on the battlefield,” he acknowledges.

The defence sector has substantial finances and it is only natural for it to invest them in the application of artificial neural networks, says Schmidhuber, who heads the Institute of Artificial Intelligence (Idsia) in Lugano.

Schmidhuber sees the potential misuse of technology as part of scientific progress; there is no way to stop it. He cites human domestication of fire as an example: it allowed the species to evolve but could also be used as a weapon. “Should we then give up fire?” he asks rhetorically.

“Most of the things that scientists invent have applications that they cannot imagine,” says Schmidhuber. “Not even Einstein could imagine all the applications of his discoveries.”

Edited by Sabrina Weiss.

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.