Swiss pension reforms continue unabated

Switzerland has not finished overhauling its pension system. The revision of the old-age pension system submitted to the people on Sunday was only the first step. It will be followed by a reform of the occupational pension system, and gender equality remains one of the major issues.

Sunday’s vote on old-age and survivors’ insurance does not mark the end of the debate on pensions. Quite the contrary.

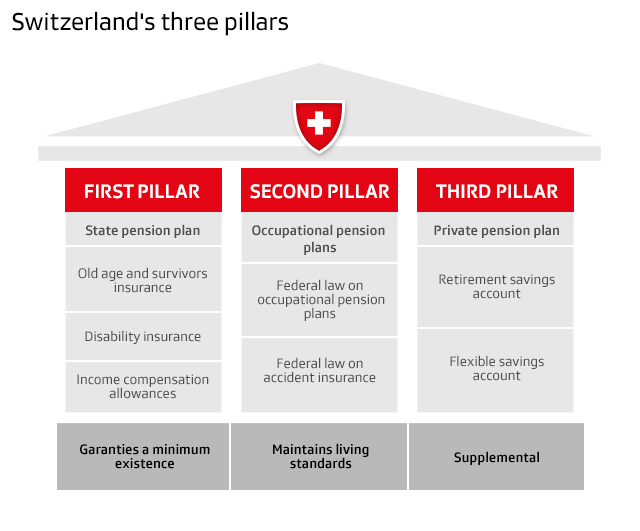

The whole system needs to be reformed to maintain the level of pensions in the long term and to reduce inequalities. This is because the amount of pension received on retirement does not depend solely on the the first pillar of Swiss retirement provisions, but also on the occupational pension scheme (also known as the second pillar) and the private pension scheme (the third pillar).

More

Swiss voters back higher retirement age for women

The state old-age insurance is supposed to guarantee the minimum subsistence level, the occupational pension scheme to maintain the same standard of living, and the third pillar to cover additional individual needs.

Although they operate differently, both the first and the second pillars are affected by the increase in life expectancy. The decrease in the number of working people in relation to the number of pensioners threatens the financial equilibrium of the two pillars. In recent years, occupational pensions have also suffered from low interest rates, which have reduced the investment returns of pension funds.

Lowering pensions

Following voters’ rejection of a first revision of the old-age insurance and occupational pension scheme in 2017, the drafts were reworked separately. The basic pillar was the first to succeed, but a reform of the occupational scheme is currently in the hands of parliament. Called BVG21/LPP21, it provides for a reduction in the rate at which capital accumulated over the years is converted into a pension.

The number of pensions will therefore fall, while the contributions (paid in equal parts by employees and employers) will remain unchanged. To mitigate the effects of this measure on the transitional generation, who will retire just after the entry into force of BVG/LPP21, the reform aims to compensate the loss of pension with a monthly supplement.

The new draft also provides for a reduction in the minimum salary from which contributions are deducted (coordination deduction), which should enable low-income individuals to participate more. This would be of particular benefit to women, as they contribute less to occupational pensions and therefore receive much lower amounts than men when they retire.

Considerable inequalities

In 2020, female pensioners received average annual pensions that were 34% lower than their male counterparts, according to a new government report. This imbalance is mainly seen in the second pillar, as only employees with a certain level of income are obliged to contribute, whereas everyone has to contribute to the financing of the basic pillar. In 2020, 70% of men were receiving an occupational pension, compared to only 49% of women. And among the beneficiaries, women received 43% less.

“When a person’s employment is interrupted or part-time, the accumulation of pension capital is slowed down,” says Brenda Duruz-McEvoy, head of social policy and a pension expert at the Centre Patronal, a Swiss employers’ organisation. She points out, however, that single women already have a similar level of pension to single men.

Carola Togni, a professor at the University of Social Work and Health in Lausanne, believes that the existence of a minimum income requirement to be able to contribute to the occupational pension scheme particularly limits women’s membership: “They are over-represented among the low and even very low earners due to part-time work, wage inequalities and the low wage value of jobs in which women are the majority”

While the employers’ organisation is in favour of completely abandoning the coordination deduction in order to strengthen savings in the second pillar, it would like to maintain a minimum income limit for affiliation to the occupational scheme.

“In order to avoid excessive administrative costs, an entry threshold should be retained, but it should take into account all the employee’s income, including that earned with other employers,” says Duruz-McEvoy.

Acting on other levels

Simply lowering the coordination deduction, as provided for in the second pillar reform, will not be enough says Togni. “In terms of benefits, the BVG/LPP reflects and amplifies inequalities in the labour market without any compensation mechanisms, unlike the first pillar, which provides for certain measures such as the education bonus or the distribution of pensions between spouses.”

She believes that the risk is that more women will contribute to the second pillar, but that this will not lift them out of poverty at retirement age. She thinks that the ongoing reforms of the first and second pillars will increase inequalities, especially for middle-class women and those on low wages or with no income. “Other measures such as an increase in wages, especially for low-wage women, would improve the financing of pensions,” says Togni.

For Duruz-McEvoy, supporting women’s participation in the labour market is a priority, while leaving each family free to organise itself as it wishes. “There are many incentives contrary to the interests of women, society and the economy that must be abandoned,” she says. She cites excessive taxation on second incomes, poorly calibrated health insurance premium subsidies and difficulties with childcare.

The bone of contention

The revision of the occupational pension scheme is currently the subject of a particularly divisive debate in parliament. Elected representatives disagree on the compensation to be granted to the transitional generation. The right wants to restrict the number of beneficiaries and the duration of the measures, which would penalise women and low-income earners, according to the left. The project has been referred back to committee to evaluate the costs of the different scenarios more precisely.

But the result of Sunday’s vote on the state old age pension is scheme is only likely to increase tensions between the two camps, as raising the retirement age for women is also a central element of the occupational pension reform.

The left is demanding strong measures in the second pillar to compensate for inequalities. But the right, which has a majority in parliament, wants to avoid costly changes and prefers to make moderate adjustments to the functioning of the occupational pension scheme. Both sides have already threatened to launch a referendum or to freeze the project permanently.

More

Translated from French; edited by Samuel Jaberg

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.