Swiss scientists uncover possible cause of mysterious hiking accident in Russia

Using topography data and computer simulations, researchers in Switzerland have put forward a plausible explanation for the mysterious deaths of nine hikers in Russia’s Ural Mountains in 1959: an unexpected avalanche.

The scientists, from the country’s two federal institutes of technology, ETH Zurich and EPFL, conducted an original scientific study into the accident that has remained an enigma in Russia. The results of the study have been published in Communications Earth and EnvironmentExternal link, a journal by Nature Research.

Their findings lay to rest some conspiracy theories that have emerged over the years to explain the so-called Dyatlov Pass Incident. Possible explanations for the accident, in which the young hikers received terrible injuries, have ranged from Soviet military experiments to a murderous Yeti.

Unanswered questions

In January 1959 a group of ten students, all experienced skiers, set off on a 14-day expedition to the Gora Otorten mountain, in the northern part of the Ural Mountains, where temperatures could be as low as -30 degrees Celsius. One member of the expedition, Yuri Yudin, turned back over health concerns.

When the rest of the group failed to return, a rescue team was sent out. They found the group’s tent on February 26, on the slopes of Kholat Syakhl – translated as “Death Mountain” – some 20 km south of the group’s destination. The tent was slashed and their belongings left behind.

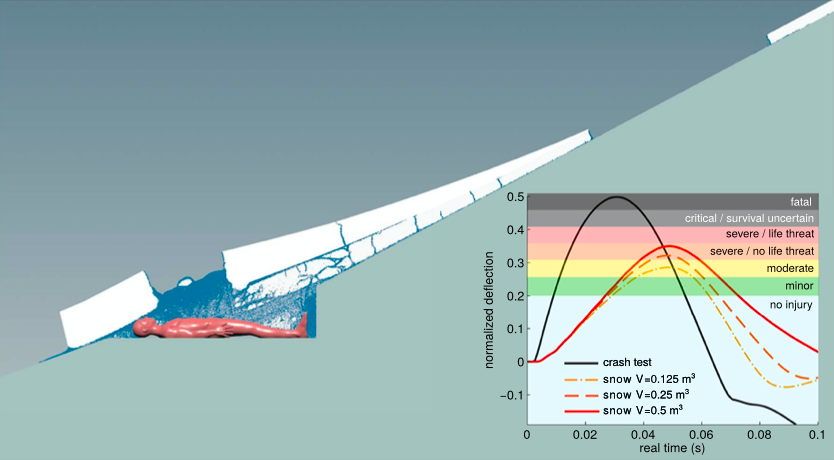

Further down the mountain, the rescue team found five bodies; the remaining hikers were discovered as the snow thawed. Several of the deceased had serious injuries, such as fractures to the chest and skull.

In 2019, the Russian Public Prosecutor’s Office completed a second investigation into the accident (the original probe of 1959 concluded that a “compelling natural force” had caused the death of the hikers), which concluded that the most likely cause was an avalanche.

But many questions remained, such as why there was no evidence of an avalanche. The slope above the tent site was not steep enough for an avalanche and the injuries were also not typical for crushing by snow. There were also questions about the timing and sequence of events that kept the incident a mystery.

Swiss collaboration

The Swiss scientists’ investigation was prompted by a call from a New York Times journalist to EPFL professor Johan Gaume, head of EPFL’s Snow and Avalanche Simulation Laboratory (SLAB) and a visiting fellow at the WSL Institute for Snow and Avalanche Research SLF. The journalist was looking for his expert views on the case.

Gaume contacted Russian-born Professor Alexander Puzrin, deputy head of the Institute for Geotechnical Engineering at ETH Zurich. They worked together, gathering information and developing analytical and numerical models to reconstruct the avalanche.

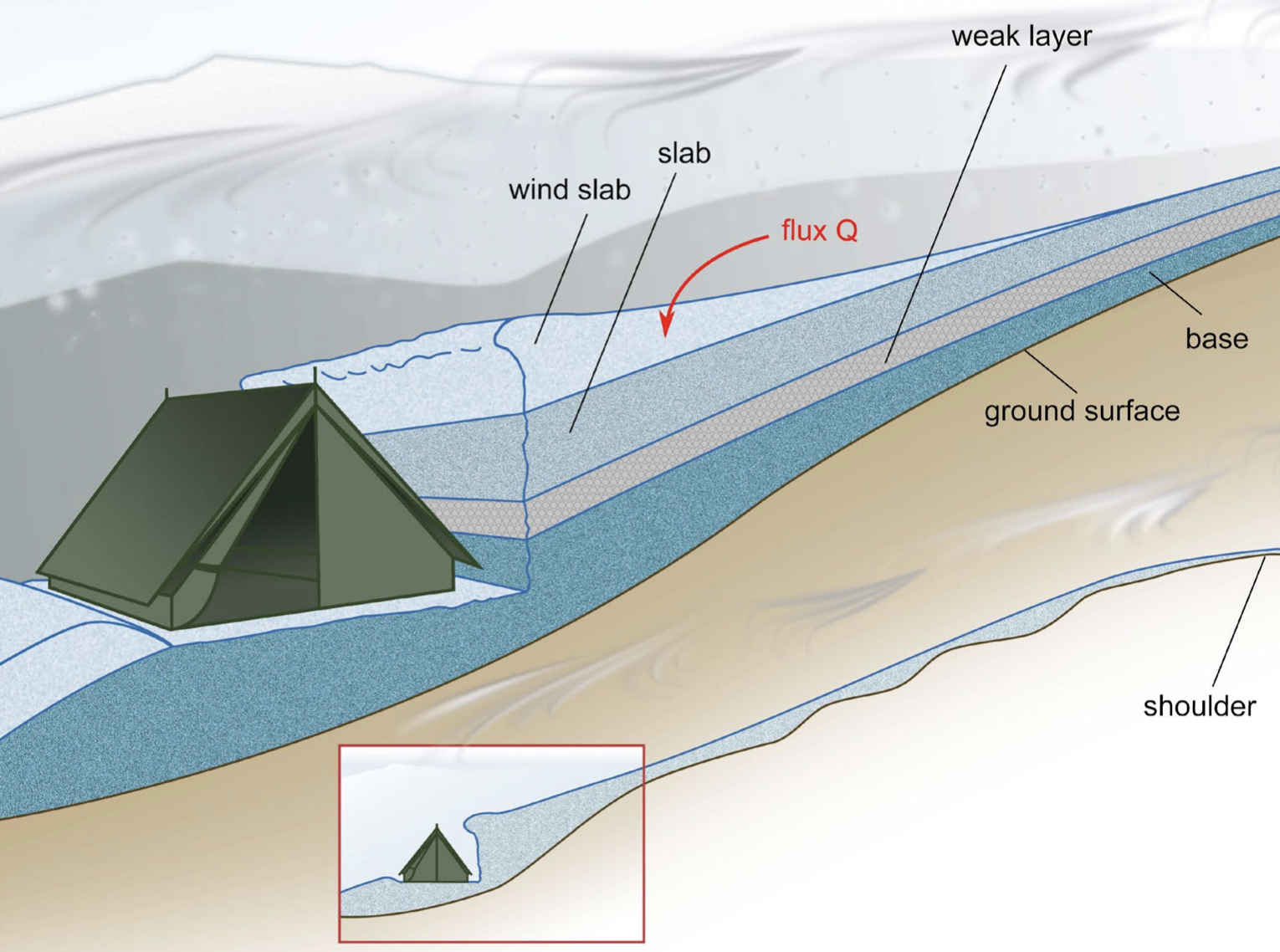

The two scientists believe the hikers had made a cut in the mountain’s snow-covered slope to set up their tent, but the avalanche didn’t occur until several hours later.

“We use data on snow friction and local topography to prove that a small slab avalanche could occur on a gentle slope, leaving few traces behind. With the help of computer simulations, we show that the impact of a snow slab can lead to injuries similar to those observed,” explained Gaume in a press releaseExternal link from ETH Zurich.

The time lag was another focus. Key here was the presence of katabatic winds – winds that carry air down a slope under the force of gravity.

These winds could have transported the snow, which would have then accumulated uphill from the tent due to a specific feature of the terrain that the team members were unaware of.

“If they hadn’t made a cut in the slope, nothing would have happened. That was the initial trigger, but that alone wouldn’t have been enough. The katabatic wind probably drifted the snow and allowed an extra load to build up slowly. At a certain point, a crack could have formed and propagated, causing the snow slab to release,” said Puzrin.

The scientists say that even with their findings, the incident still remains a mystery. “The truth, of course, is that no one really knows what happened that night. But we do provide strong quantitative evidence that the avalanche theory is plausible,” Puzrin pointed out.

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.