Why current air pollution limits only tackle half the problem

Switzerland-based scientists tell swissinfo.ch why a comparison between air samples from Swiss farmland and downtown Beijing suggests that setting pollution restrictions based on particle mass concentration alone may not be enough to protect against health risks.

On June 1 of this year, Switzerland’s environment ministry enacted stricter controls on air pollutionExternal link; specifically, on particles with diameters equal to or smaller than 2.5 micrometers.

The new regulation complements the air quality standards for PM10 (suspended particles with diameters equal to or smaller than 10 micrometers) to better protect against extremely fine pollutants – which can lead to respiratory illnesses as well as cardiovascular disease and cancer – in accordance with World Health OrganizationExternal link recommendations.

But recent research from EmpaExternal link, the Swiss Federal Laboratories for Materials Science and Technology, suggests that air quality control could be improved by accounting for regional differences in the chemical composition of these particles…and not just their mass concentration.

“The current practice could lead to inadequate health protection for one region, but unnecessary economic costs for another without achieving significant extra health benefits,” Empa scientists Yang Yue and Jing Wang conclude in their paper, which was published earlier this year in the journal Environmental Science and TechnologyExternal link.

Quality, not just quantity

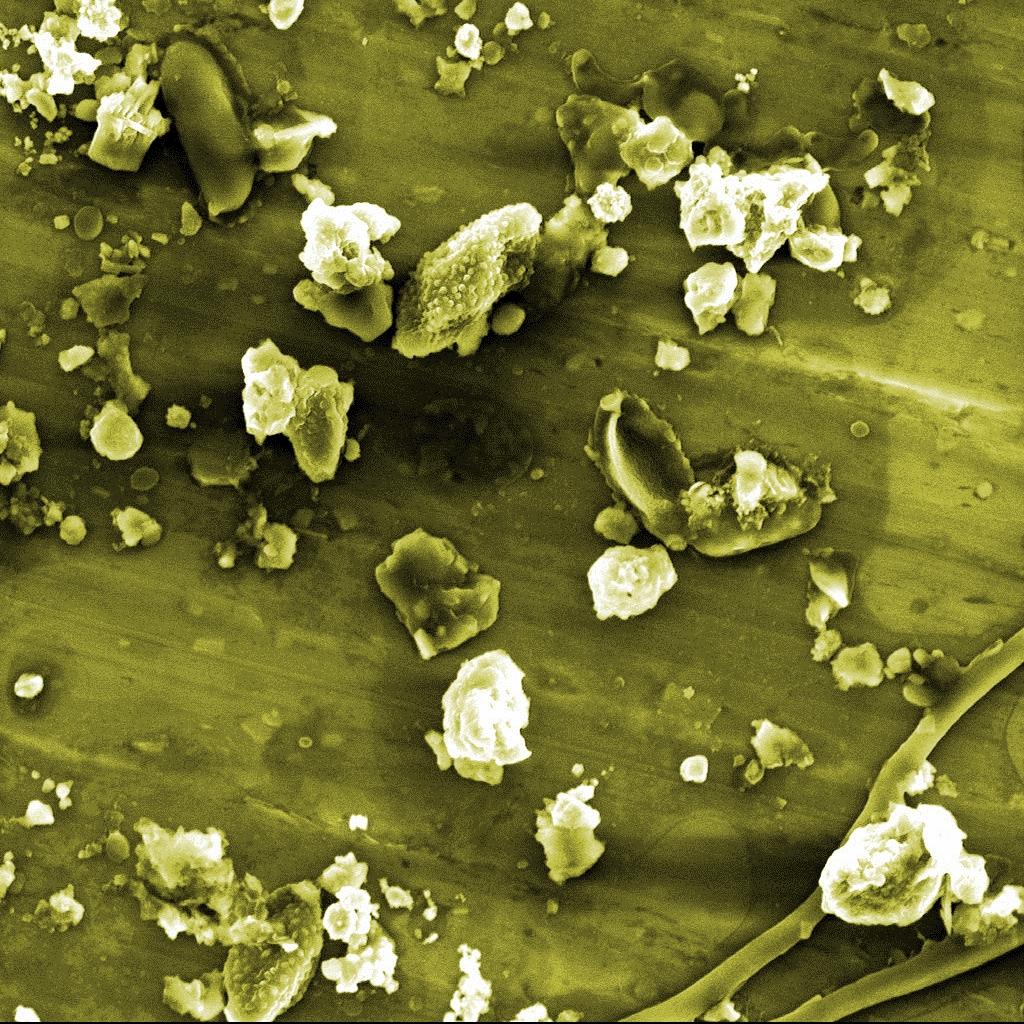

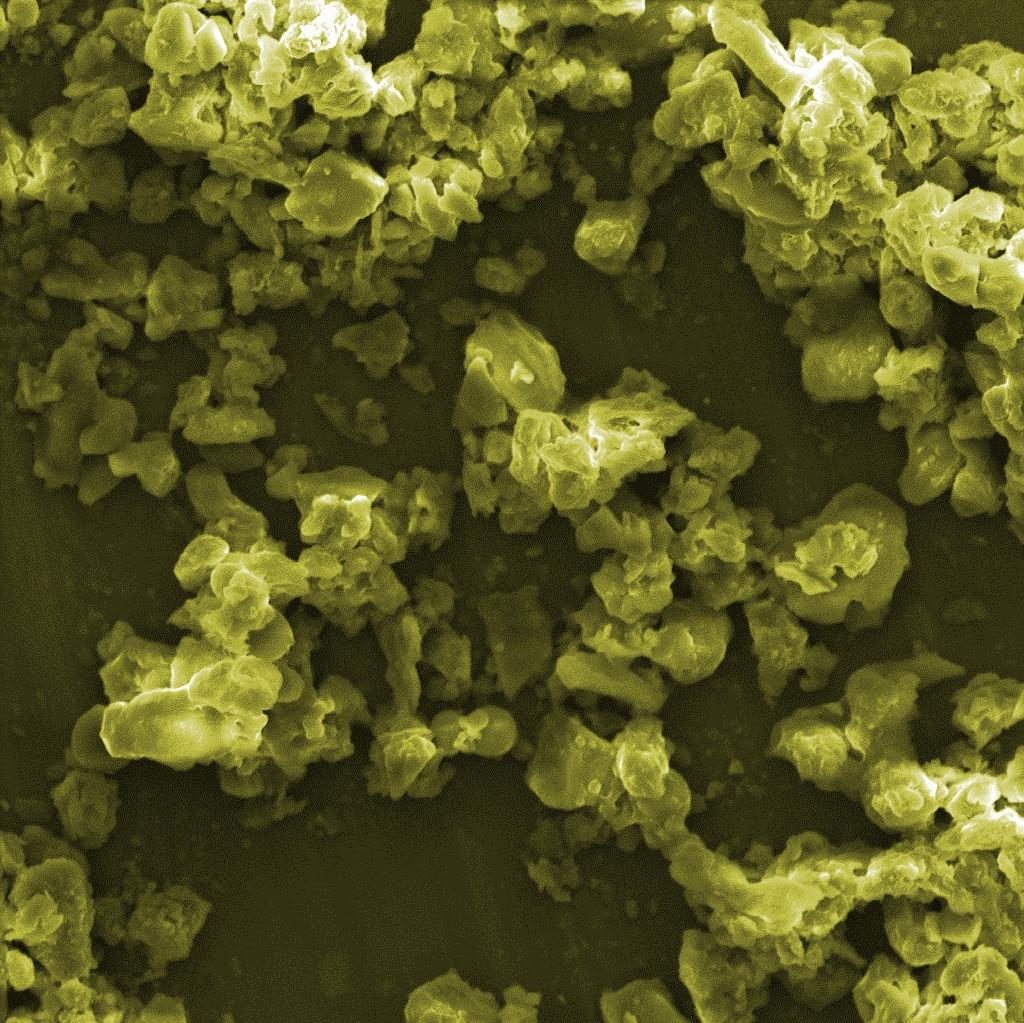

Yue and Wang, from Empa’s Advanced Analytical Technologies labExternal link, reached this conclusion by studying air samples from stereotypically clean Switzerland as well as China – a country whose air pollution problems are well known.

But their results weren’t so black and white.

The researchers studied something called the oxidative potential of PM found in the samples from the two countries – in other words, the potential for the chemicals contained within those particles to harm human cells and tissues through a phenomenon called oxidative stress (see box).

They found not only that the oxidative potential of the air pollutant particles varied widely, but that an air sample from a Swiss farm actually had higher oxidative potential – in other words, it scored worse in this regard than a comparably polluted sample from a main street in metropolitan Beijing.

So, does that mean that Swiss air quality is just as bad, or worse, than in China?

“No, this understanding is incorrect,” the two researchers told swissinfo.ch.

While some Swiss samples carried a higher oxidative potential than those from China – and therefore a greater potential health risk – when pollutant particle concentrations were compared, the Swiss air also contained fewer particles overall.

“If we calculate the oxidative potential by equal volume of air, the Swiss air would have lower oxidative potential than Chinese air due to the significantly lower PM concentration in Switzerland. Humans inhale similar volumes of air, but not the same mass of PM. Thus, we cannot say the air on the Swiss farm was worse than the air from the Beijing urban main street,” Yue and Wang explained.

“We also found significantly lower concentrations of heavy metals, e.g. cadmium, lead and arsenic, as well as endotoxin [a bacterial by-product commonly found in farming environments] in Swiss air than in Beijing air,” the researchers added.

The oxidative potential of Swiss samples from the Zurich suburb of Dübendorf also scored high due to iron, copper, and manganese particles sent into the air by the abrasion from a nearby railway line.

Oxidative stress occurs when the body is exposed to too many unstable, highly reactive molecules called free radicals, which can damage cells and tissues through a chemical process called oxidation. Some free radicals are found in the body naturally, but they can also be introduced via external substances – like cadmium, arsenic or soot particles found in polluted air.

Compounds called antioxidants – some of which are produced naturally in the body and some of which are consumed through food – interact with free radicals and stop these damaging oxidation reactions. Oxidative stress can occur when the body’s antioxidant defences are overwhelmed, and some evidence points to the involvement of oxidative stress in the development of neurodegenerative and cardiovascular diseases, as well as cancer. But while dietary antioxidants can be beneficial to health, there is little scientific evidenceExternal link that antioxidant supplements offer any benefit, and can even be harmful in some cases.

A change for pollution policy?

Swiss air may not be ‘worse’ than Chinese air when pollutant concentrations are considered, but the Empa scientists believe their findings suggest that more efficient measures could be applied for air quality control.

“The effects of fine particles on air quality and health cannot be assessed solely on the basis of their mass,” Wang summarised in an Empa press releaseExternal link. “But if the composition of particulate matter is known, a regionally adapted health protection can be implemented.”

The Empa team is now trying to establish a way to analyse PM chemical composition more precisely, with an eye toward identifying dangerous compounds more easily.

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.