Switzerland’s pioneering carbon offsets strategy raises questions

To meet its climate goals, Switzerland has committed to offset part of its emissions abroad. As the world questions the credibility of carbon markets, the country stands by its strategy.

In the bustling streets of Bangkok, a blue fleet of electric buses has been transporting locals and tourists amid honking scooters and cars for just over a year. Compared with their predecessors, these buses are quieter, cleaner and, above all, emission-free. But Thailand cannot claim the CO2 emissions saved – Switzerland will.

Switzerland has set itself the goal of halving its emissions by 2030 compared with 1990 levels. To achieve this, it has signed bilateral agreements with developing countries such as Thailand and supports climate projects there, which is cheaper than measures at home. In fact, Switzerland plans to save around 43 million tonnes of CO2 equivalents or a third of its total emissionsExternal link, in this way.

The deal with Thailand was signed in 2022 and in December last year the bus project was the first ever to be approved for emissions trading. This comes at a time when wealthy countries are increasingly criticised for relying on developing countries to reduce emissions on their behalf.

While the approval marks the young history of carbon offsets between two countries, it also raises many questions. How transparent is the certification process? Do such projects actually meet the conditions set by the Paris Agreement on climate change? And has Switzerland given itself the means to meet its climate targets through so-called carbon offsets?

“Switzerland is the first country that has actually managed to see such bilateral agreements through to the end,” says Axel Michaelowa, a researcher at the University of Zurich and partner in the consultancy Perspectives Climate Group, who advises the UN and individual countries on the implementation of such agreements and carbon offset markets.

“Of course, there are very few projects at the moment because everything has just started. In the future, if dozens of projects are running at the same time, how will Switzerland ensure that the projects are treated in an equal manner?” he asks.

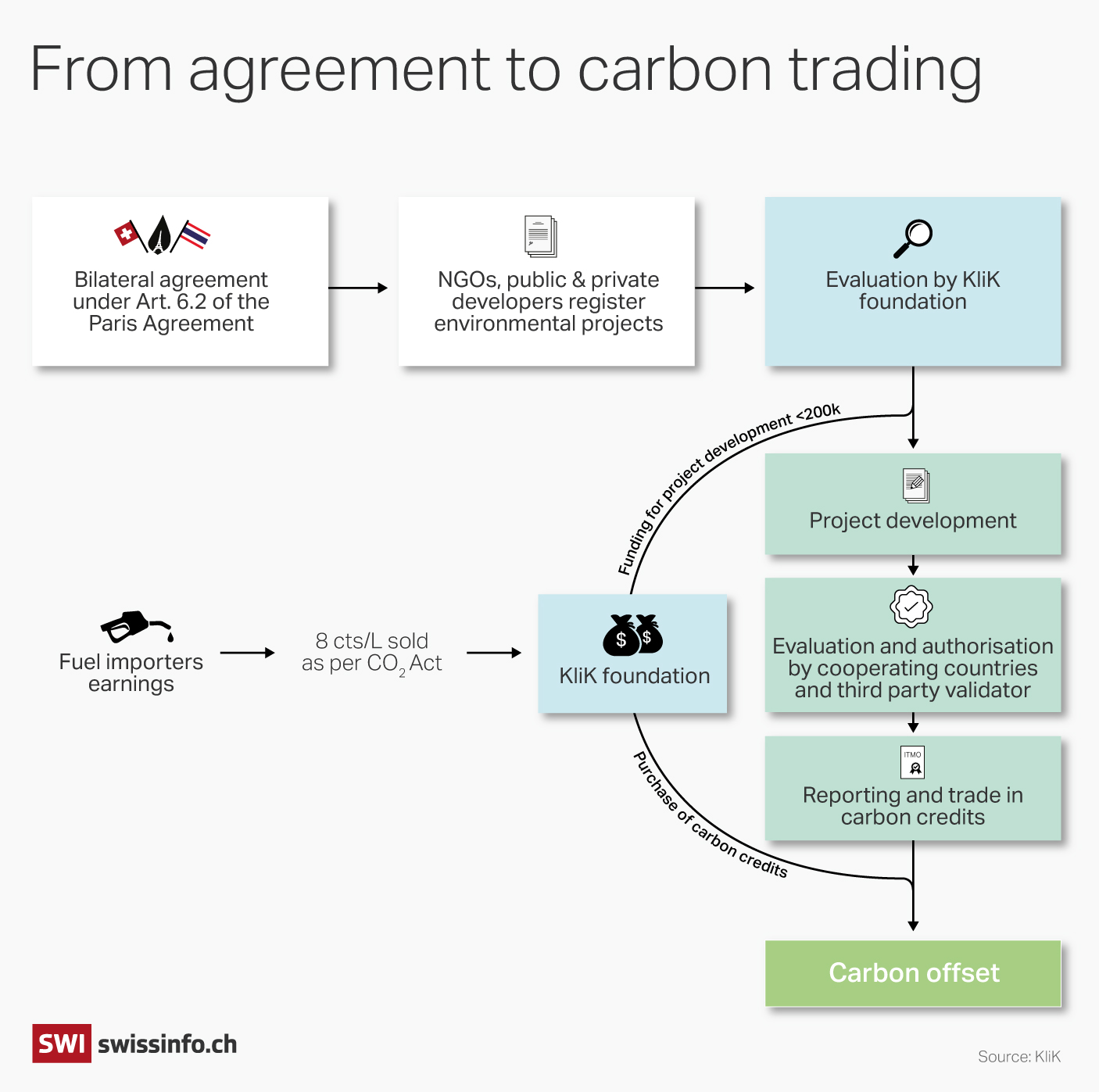

From a political deal to emission credit

The journey from a bilateral deal between two countries to the trade of emission credits is a long and cumbersome one. Although Switzerland has signed deals with 14 countries since 2020, so far few have been turned into measurable actions. Apart from the Thai project, two more have been approved by the Swiss government, one in Ghana and one in Vanuatu. It’s unclear when other projects will see the day and begin selling credits.

Once Switzerland has signed a bilateral agreement with a country, in principle, any company or industry association that wants to offset its emissions could buy credits from projects in these countries. To do this though, they first need to find a viable project that fits the criteria set by the Paris Agreement, a legally binding international treaty on climate change signed in 2015.

So far, only a Swiss foundation called KliK and the federal administration are offsetting emissions overseas. KliK was set up by petrol station operators and fuel importers to fulfil their legal obligation to compensate emissions. It’s financed by CHF0.08 ($0.09) per litre of petrol sold to drivers. Those add up as the capital that KliK then uses to buy credits from environmental projects in Switzerland and abroad.

Before KliK can buy credits, it must have them certified by the Swiss government. This is what happened in December 2023, when the Swiss Federal Office for the Environment (FOEN) approved the initial report submitted by Energy Absolute – the Thai project owner – and Swiss consultancy firm South Pole. The report says that the replacement of old buses with 550 e-buses resulted in a reduction of 1,916 tonnes of CO2 emissions between October and December 2023.

Energy Absolute can now sell the credits, so-called Internationally Transferred Mitigation Outcomes (ITMOs), with one tonne of CO2 corresponding to one credit. The proceeds from these sales help Energy Absolute recover what it has invested in 2,000 buses so far. KliK is the sole buyer of these credits, thanks to a contract they signed with the Thai company.

Unachievable carbon offset targets?

The process, though a possible blueprint for othersExternal link, leaves many questions unanswered.

The main one is the gap between Switzerland’s stated goal of offsetting up to 43 million tonnes of its emissions overseas and how quickly ITMOs can be issued and traded as the 2030 deadline looms. The KliK Foundation plans to offset at least 20 million tonnes of CO2 emissions with foreign projects by 2030. The foundation currently has its eyes on ITMOs from 18 projects, but these are still in development and would cover only half of its 2030 target.

More

What Is Carbon Offsetting? Explained in 2 Minutes

That doesn’t seem to worry Michael Brennwald, Head of International at KliK. “The remaining potential in Switzerland for mitigation activities under the current domestic scheme is limited. The potential for developing mitigation activities abroad, on the other hand, is enormous,” he writes in an email. Above all, it is much cheaper to finance environmental projects abroad than in Switzerland.

Six out of the 18 pilot projects in the pipeline are still pending final approval by the authorities. None of the project owners contacted gave SWI swissinfo.ch a date as to when trading in credits would begin. Some said that legal frameworks in the host countries weren’t in place yet, causing implementation delays.

Approval process is a black box

A closer look at Switzerland’s approval process also raises questions. For credits to be traded, Switzerland has to approve preliminary findings which show projects do in fact reduce emissions.

Currently, Switzerland and its partner countries can decide how they want to evaluate and approve projects. The Federal Office for the Environment has not specified the methods for calculating the volume of emission credits but assesses each project proposal separately. This makes it difficult to ensure the quality and credibility of these credits, according to climate policy expert Michaelowa. “The FOEN can basically apply different methodologies as it sees fit,” he says.

Michaelowa refers to the methodology as a black box. His consultancy supports projects in the cooling sector in Ghana and Morocco by writing the documents that they have to submit to both the FOEN and the local governments in order to receive approval. “We send the documents to the FOEN and don’t know exactly what will come back,” he says.

The FOEN stands by its approach of evaluating each project individually instead of resorting to standard methods. The Thai e-bus project is the third to be approvedExternal link under Switzerland’s climate deals. A spokesperson wrote in an email response to SWI swissinfo.ch that this flexible approach would allow new findings to flow more quickly into ongoing projects. They added that experience with 200 compensation projects in Switzerland showed that the FOEN treated the projects equally when evaluating them.

The few provisions on bilateral carbon offsets are defined in Article 6.2 of the Paris Agreement. One of the main conditions is that the “host country” receives a financial boost for projects that would otherwise not have come about. This criterion of “additionality” for emissions abroad is so crucial that it’s inscribed in the Swiss CO2 law, but it’s nonetheless quite difficult to assess.

Thailand does indeed benefit from the agreement it signed with Switzerland. This deal does not involve direct aid or subsidies from Switzerland but creates a market mechanism through which the two countries can trade ITMOs. “It is only through this programme that we can afford to replace buses with internal combustion engines and make a significant change,” says Norasak Suphakorntanakit, assistant vice-president at Energy Absolute, the Thai company that started developing the project with South Pole back in 2020.

A recent analysis by Alliance Sud and FastenaktionExternal link casts doubt on the “additionality” of this project: The two Swiss NGOs point out that the electric buses in Bangkok would likely have been rolled out even without the agreement with Switzerland and the associated funds. Both the FOEN and KliK told Climate Home NewsExternal link, in response to the claims, that only projects generating additional emission cuts would be approved.

Carbon offset backlash

Carbon offsets were once again the subject of heated debate at the latest UN climate talks (COP28) in Dubai, with delegates from nearly 200 countries disagreeing on fundamental issues such as the level of transparency.

More

Where the world – and Switzerland – stands on carbon offsets after COP28

Just prior to this, the voluntary market where citizens can choose to compensate a flight for a few francs, for example, came under fire for exaggerated claims. South Pole, the world’s leading seller of carbon offsets, was forced to drop its flagship reforestation project in Zimbabwe and several executives have since resigned.

Switzerland will continue to pursue its bilateral path to carbon offsetting. In Dubai, Environment Minister Albert Rösti signed further deals with Chile and Tunisia. “With such international projects, where there are so-called low-hanging fruits, we can reduce CO2 more quickly than by implementing additional, difficult and expensive CO2 reduction measures in Switzerland,” Rösti told Swiss public broadcaster SRFExternal link.

Edited by Virginie Mangin

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.