The expedition comes to an end

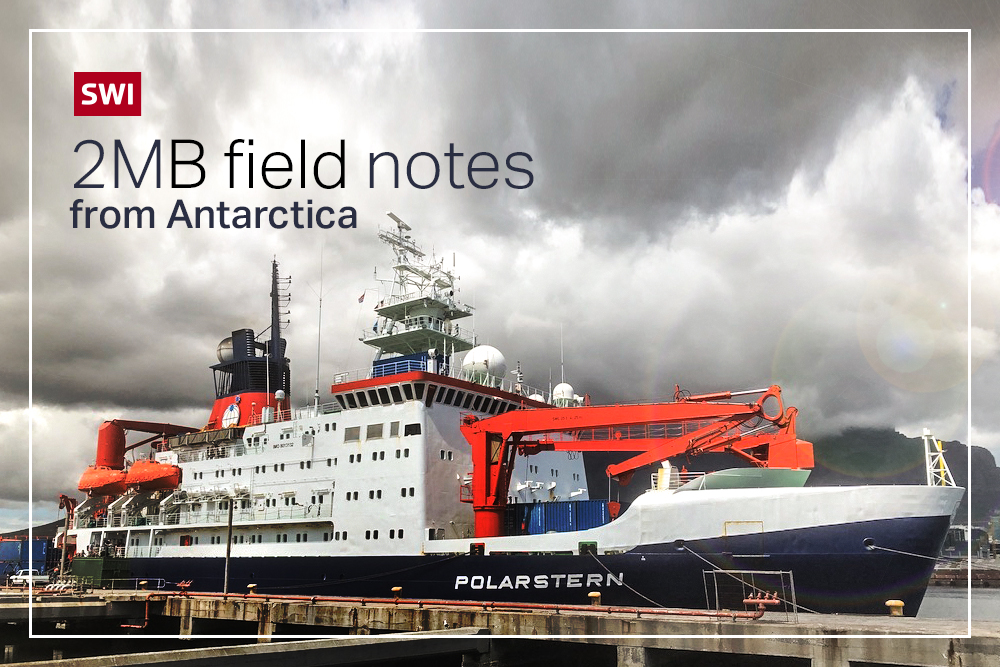

Our Antarctic expedition ended in Punta Arenas, Chile, and almost all scientists left the Polarstern research vessel, except for a marine chemist and me. We were, however, joined by two new scientists who study the submarine topography of the Atlantic, i.e. essentially 3-D mapping the ocean floor. Including the meteorologists on board, we now form a jolly, family-like group of seven and have settled in for the Atlantic transit, which takes the vessel back to its home port in Bremerhaven, Germany. There was only one brief stop at the Canary Islands to pick up a group of students.

My aim is to continue studying the colonisation of bacteria on plastic by incubating the plastics in sea water and taking water samples. Even though the latter may seem strange, the seas are home to many different species of bacteria and even a single drop of seawater contains about a million bacteria. These bacteria are important for biogeochemical cycles and global oxygen production; about half of the oxygen that you breathe comes from marine systems. Some of the bacteria from the water settle on floating plastic and form communities there.

In comparison to free-living cells in the water column, the bacteria in biofilms interact much more strongly with each other and the plastic provides them with a more stable environment. But even so, the growth of these so-called biofilms is dependent on external conditions, such as the availability of nutrients, temperature and light. All of these factors change as the Polarstern steams through the Southern Ocean and then north through the Atlantic. Therefore, by continuing our experiments, we want to find out if and how the bacterial communities on the plastics differ in these regions.

2MB field notes from Antarctica

Just 2MB a day?! That’s the data limit for the authors of our polar blog. This spring, Gabriel Erni Cassola (right) and Kevin Leuenberger (left) from the University of Basel are on board the German icebreaker “Polarstern” in the Southern Ocean. The researchers want to find out how animals and bacteria in the Antarctic are affected by microplastics. In this blog series they give us insight into their work and life on board a polar expedition.

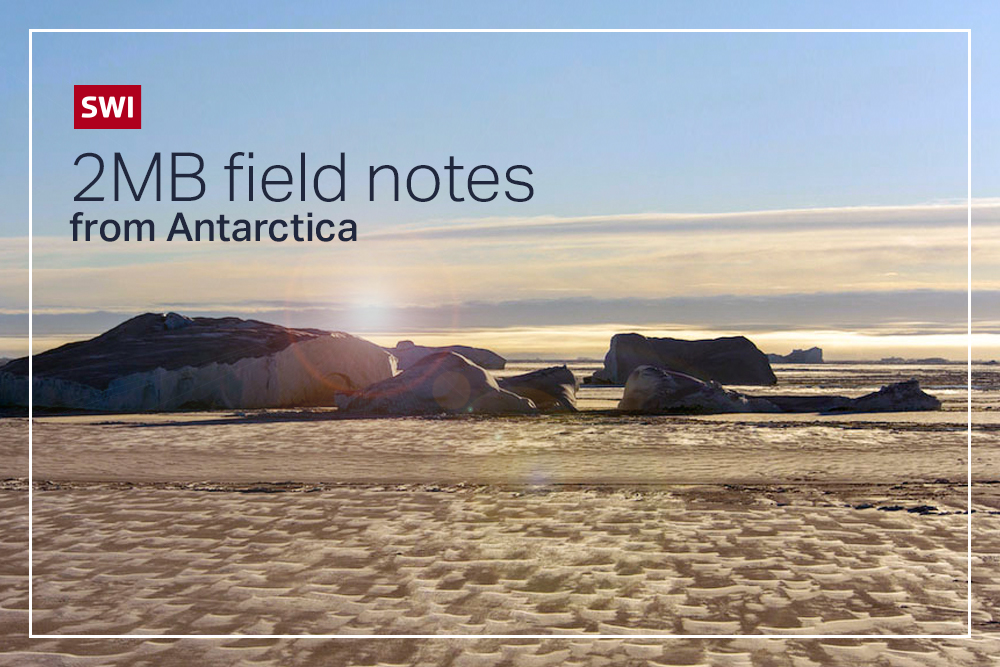

Daily life aboard the Polarstern differs in a few ways from the usual work routines at the University of Basel. Since the scientific work has to be done whenever the ship reaches a designated research station, the working schedules are dictated by the expedition route. Weekdays lose their meaning, and so the weekends are non-existent. During the most intense research periods, such as in Antarctica off the ice shelf, this can also mean that sleep is often cut short because processing samples or deploying gear becomes the top priority; and all of these activities are made possible thanks to a crew that works in shifts to provide 24-hour support, seven days a week.

To make some days special, however, we are treated to ice cream every Thursday and Sunday! In general, meals are one of the few fixed times when I get to meet and chat with other people I might otherwise hardly get to see, because they work in a different section of the vessel. These meals can also bring great joy. After two months at sea in Antarctica, most of the fresh food had run out and so we enjoyed the fresh salads and fruit we got in Chile, as well as the fresh strawberries from the Canary Islands.

During our crossing through the Atlantic, nature hasn’t failed to impress us with a partial solar eclipse, a lunar eclipse, erasing practically all shadows on the ship with the sun at its almost perfect zenith at 89°, and mahi-mahi visiting us during an experiment.

After three months of research at sea, however, I am now happy to return home, cook my own meals, and meet up with friends. My colleagues and I will soon turn our attention to all the water samples and data we’ve collected. In our university labExternal link, we’ll look at how widespread microplastics and bacteria are in the Antarctic Ocean, one of the world’s last frontiers. Stay tuned for findings from our research project!

Scroll down to read previous entries by Gabriel and Kevin. The 2MB field notes will soon arrive from a place on the other side of the world: the Norwegian archipelago of Svalbard. From July, a group of ecology and earth sciences PhD students at the Swiss Federal Technology Institute ETH Zurich will be investigating the greening of the Arctic due to warmer temperatures. To receive future editions of this blog in your inbox, sign up for our science newsletter by entering your email address in the field below.

More

2MB field notes from Antarctica

More

Why are we looking at plastic pollution in the Antarctic?

More

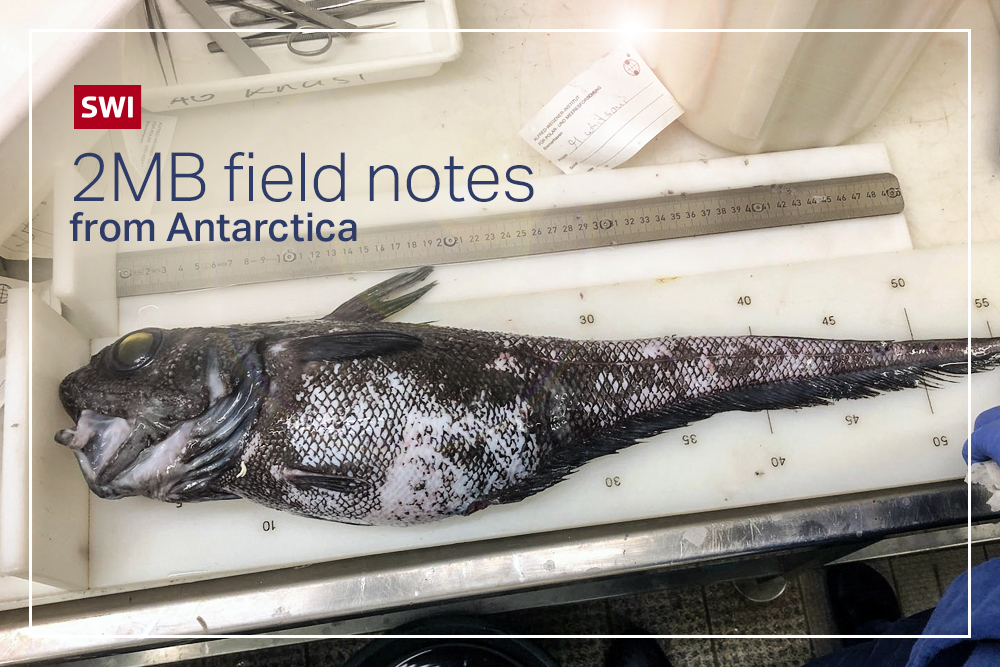

Is plastic on the menu of Antarctic fish?

More

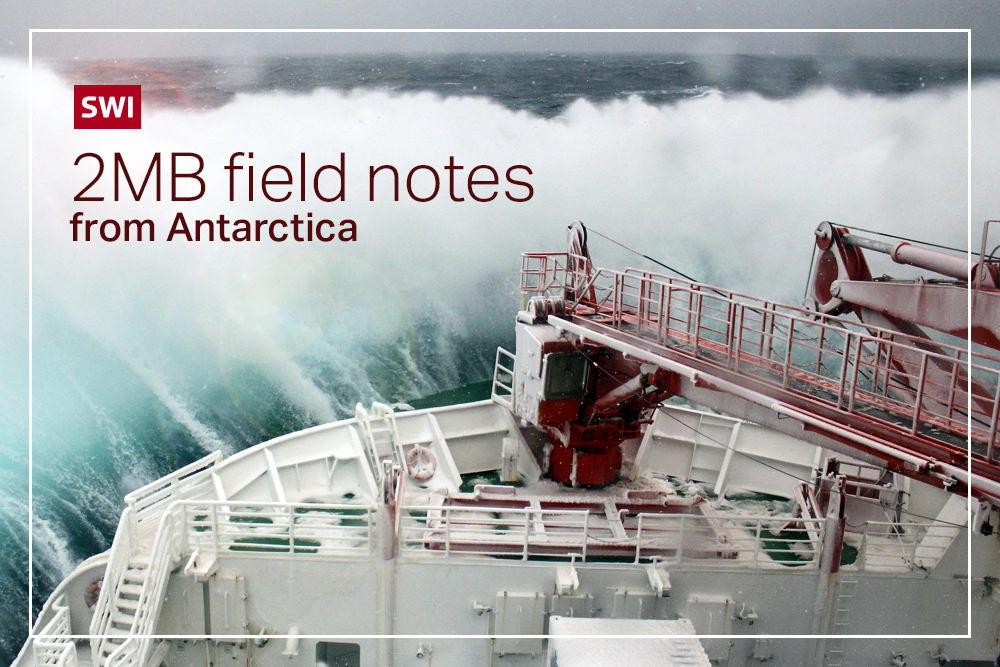

When storm ‘Gabriel’ hit the Weddell Sea

More

Microplastics research in the Antarctic often requires creative solutions

More

A surprise sighting: Ukraine’s stranded research vessel

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.